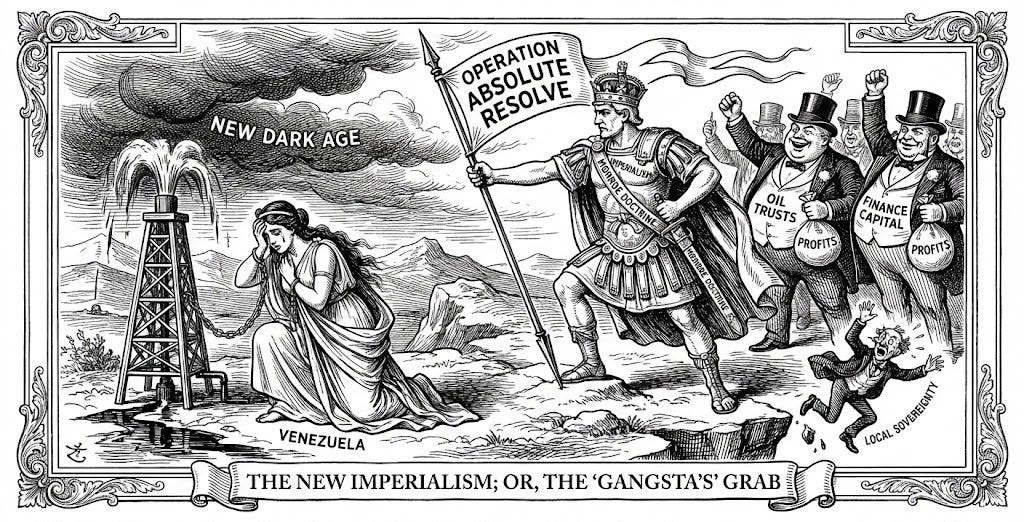

A New Dark Age

Operation Absolute Resolve marks the end of the old international order

While awful and terrifying, there is something at least clarifying about this “extreme gangsta” moment in American life and American history. While many commentators express outrage at the aberrant lawlessness of Trump’s blatant imperialism, decrying his attack on Venezuela as a break from the past, one could just as easily focus on the continuities and familiar historical patterns. By bypassing Congressional oversight and international law to seize direct control of foreign assets, the Trump regime has signaled that the “New Dark Age” involves the end of the old international order along with a return to a raw, resource-based imperialism. In what follows, I am going to review some of the historical and immediate context that led to Operation Absolute Resolve, saving my commentary for upcoming columns.

We’ve been manipulating Venezuela to gain control over its copious natural resources for over a century. After oil was discovered in Venezuela’s Lake Maracaibo region in 1914, American oil companies rushed in to profit from it. By the 1920s, Venezuela had become the world’s second-largest oil producer after the United States itself. Companies like Standard Oil, Gulf Oil, and later what would become Exxon and Chevron dominated Venezuela’s oil industry for decades. As historian Miguel Tinker Salas documents, these companies didn’t just extract oil—they created entire company towns, controlled local governments, and shaped Venezuelan politics to protect their interests. In The Pull of the Land, Salas writes:

Venezuelan production was concentrated in the interior of the country, where infrastructure and sanitary conditions had improved little since the 19th century. To ensure operations, foreign companies took charge of basic services including electricity, water, sewage, roads, housing, health services, schooling and a commissary. In these rural areas, the companies supplanted the state, and local communities became dependent on foreign enterprises for basic services.

This arrangement worked until 1976, when Venezuela nationalized its oil industry and created PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.), inspired by the example set by Libya. Even after nationalization, American companies maintained significant contracts and influence. The real break came with Hugo Chávez’s election in 1998. As Latin American historian Greg Grandin explores in The Nation, Chávez’s crime was not that he was a dictator. His crime was redirecting oil revenue away from foreign corporations and the Venezuelan elite toward social programs for the poor—healthcare, housing, education. Between 1999 and 2011, poverty in Venezuela fell from 50% to 30%, and extreme poverty dropped from 20% to 7%, according to the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

The Gini coefficient—which measures income inequality—fell from nearly .5 in 1998 to .39 in 2011, dropping Venezuela to among the lowest inequality in the Americas, behind only Canada in the Western Hemisphere. As Grandin notes, this was the polar opposite of the direction of the U.S. economy in that same period. After 1980, “no other wealthy nation deregulated, outsourced, deindustrialized, and imposed austerity as gleefully as did the United States. And few did so while also gutting the institutions—welfare, unions, housing, farm communities, hospitals, mental-health care—that might have softened the blow.” Grandin points out how Bill Clinton, during a period of economic expansion with no major competitor on the horizon, “ramped up police and prison spending and began targeting undocumented laborers. The United States’ political class treated the country as occupied territory and its citizenry as belligerents.” As I said, where we are today in the U.S. is part of a long continuum.

In 2002, Chávez was briefly removed in a US-backed coup. As Jeremy Scahill reported for The Intercept, documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act reveal that the CIA knew of the plot in advance and that the Bush administration had funded opposition groups for years. Senior officials met with plotters, refused to condemn the removal of a democratically elected government, and falsely claimed Chávez had resigned. The coup collapsed within two days as millions of poor Venezuelans poured into the streets, but after Chávez died in 2013 and Nicolás Maduro took power, U.S. strategy shifted from quick regime change to economic strangulation.

In 2015, President Obama declared Venezuela an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security of the United States.” In 2019, the Trump administration imposed an oil embargo that severed Venezuela from the global financial system. Production slowed drastically. Economists estimate these sanctions caused tens of thousands of deaths by preventing the import of medicine, insulin, and medical equipment. The goal—much like the Nixon-Kissinger strategy in Chile—was to disrupt the economy until a popular revolt or the military toppled the government. It is likely that a Democratic President would have pursued a similar policy, albeit with more Congressional support; notably, potential 2028 Democratic contenders like Gavin Newsom had nothing to say on social media yesterday about the military operation to remove Maduro, despite its blatant illegality.