This is Part Five of an ongoing thought stream. If you want to read it from the start, here are links to Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Part Four. See info about new courses at the bottom. A new month-long writing workshop starts next Weds. Please join us. 25 people max.

Analytic Idealism

Let’s review what we have discussed so far.

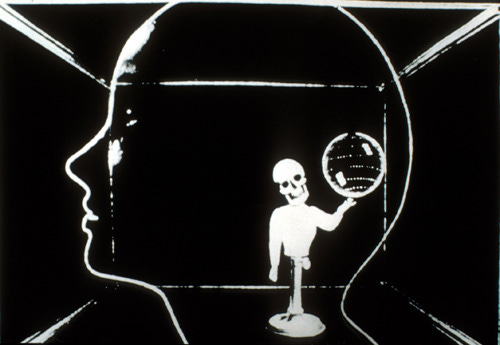

We began with a brief survey of Bernardo Kastrup’s philosophy. Kastrup proposes a metaphysical model of “analytic” or monistic idealism: There is only one thing in the universe, and that thing is not matter, but mind. The universe is the projection of an instinctive, unitary consciousness. This consciousness employs matter to reach new levels of self-reflection and creative manifestation. Ultimately, all physical things are like the objects we encounter in dreams, unreal and illusory, created from “mind stuff.” Kastrup bolsters his argument with the experimental results of quantum physics, along with statements from the scientists who made the original discoveries in this field.

A fascinating book!

Individually, we are the dissociated projections of this underlying, unitary consciousness. At death, we are reintegrated back into this primordial source, which, Kastrup proposes, we will experience as an expansion rather than an obliteration of self-awareness. He supports this with evidence from near-death experiences and psychedelic trips. Studies into the periphery of conscious experience, via NDEs or DMT, suggest that physical death is not the end, but the entry point into other dimensions or aspects of consciousness.

Paid subscribers support my work and occasionally receive special things.

Kastrup proposes that idealism resolves the insoluble paradoxes of materialism, including the “hard problem” of consciousness. Monistic or analytic idealism has profound implications not just for each of us as individuals, but for civilization as a whole. The ideology, the metaphysical belief system, underlying the last two centuries of capitalism was reductive materialism, or “physicalism,” expressed by philosophers like Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, and Bertrand Russell.

Along with Kastrup, I propose that we are going to make an inevitable transition from reductive materialism / naive “scientism” to analytic or monistic idealism as our paradigm. Just as the shift from Christian eschatology to materialism had a massive impact on humanity, the metaphysical shift we are currently undergoing will, eventually, cause profound changes across all areas of society, potentially leading to a far-reaching political-economic metamorphosis. In later sections, we will explore and seek to delineate where this could lead.

When people believe they live in a purely random universe where consciousness is an accidental byproduct of physical evolution, they may seek to accumulate capital (Karl Marx wrote about how an illusory or abstract “sense of having” takes primacy over the physical senses). They may over-consume resources, try to dominate and control nature and other human beings. They extend the lifespan as long as possible via medical interventions. They operate under the tragic assumption that nothing of value exists outside of the physical, sensorial realm. Since death is total annihilation, life is meaningless. Therefore, you should “get it while you can.”

Capitalist Realism

We looked at Mark Fisher’s book, Capitalist Realism, which argues that capitalism disguises its ideological operations by making it seem that this system is both natural and inevitable. The overwhelming effects of capitalism support the sense that there is no way out, no escape possible. Capitalist realism is a natural extension of the reductive materialist paradigm, which has been our reigning mythology for the last few centuries.

Despite its extraordinary success in merging the world into one giant market and accelerating technological innovation, capitalism, in its current form, cannot continue without destroying the planetary ecosystems we rely on for our existence. The current global order has proved itself incapable of addressing the dire threat posed by global warming and species extinction. Therefore, even though “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” we must try to do exactly that.

Governments, the financial elite, and corporations are all part of one political-economic system. Capitalism is dynamic but unstable, constantly needing to expand by creating and exploiting new markets. A steady state or degrowth version of capitalism is impossible to imagine.

The seeming rationality of capitalism hides many forms of irrationality, which are often not addressed or discussed. To take just one example, lightbulbs were developed in the 1930s that last for over one hundred years. Yet the ones we buy today fizzle out after eighteen months, so that manufacturers can make profit. It is the same across most industries. We could have durable goods that last for generations. Instead, due to “planned obsolescence” and “conspicuous consumption,” we live in a world deluged by poorly made, disposable products that cause pollution and toxic waste.

The mental health crisis is not caused, primarily, by the individual’s failure or by genetic flaws. It is a result of systemic distortions that engender insecurity, anxiety, jealousy, depression, and competition. Just as we could have durable products by now, our society could also have been reorganized to progressively reduce working hours and emancipate more time for love, self-directed learning, creativity, and self-reflection. Instead, corporations hire advertisers to promote“false needs” that require new consumer goods.

The current psychiatric approach downplays the social or political-economic roots of mental illness, which can only be addressed through social change. Instead, psychiatrists prescribe medications to “normativize” the individual, reducing their sensitivity so they can function in a competitive, insecure, destructive society. As Fisher writes in Capitalist Realism: “We must convert widespread mental health problems from medicalized conditions into effective antagonisms. Affective disorders are forms of captured discontent; this disaffection can and must be channeled outwards, directed towards its real cause, Capital.”

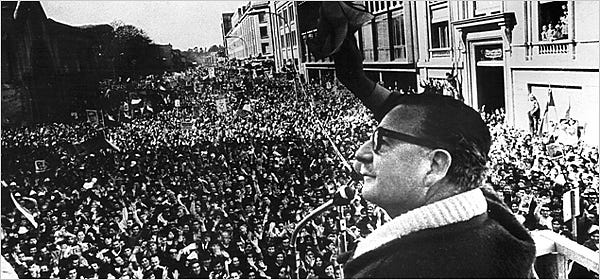

The US backed the coup overthrowing Salvador Allende’s government.

Since the 1970s, neoliberalism triumphed over Leftist/socialist alternatives — not simply due to its economic logic but because it was backed by the world’s most powerful military and intelligence forces. An often-cited example is what happened in Chile, which elected Salvador Allende, a Democratic socialist, in 1970. The forward-thinking Allende government intended to use computers and cybernetic systems to maximize the benefit of their socialist policies. This new approach was considered an existential threat by the United States, which orchestrated a coup against Allende. After Allende’s death in 1973, the US-backed government implemented a Neoliberal economic plan in the country, privatizing public resources and selling off infrastructure. This became the model for Neoliberalism around the world.

The last fifty years saw the rise of an abstract “financialized” mode of capitalism, based on immaterial financial products like junk bonds, hedge funds, and collateralized debt obligations or CDOs, rather than the production of real goods and services. The collapse of the global financial system in 2008 was a result of the growth of this new financialized form of capitalism. The bankers and speculative investors who caused this collapse — in which three million people lost their homes — did not go to jail. They continued to receive seven figure bonuses, while the financial system they control was not significantly reformed.

Despite skyrocketing wealth inequality, ongoing ecological destruction and the mental health epidemic of the last decades, the traditional Left has made no progress and has, instead, stagnated. Unions are dismantled while social services are privatized. In the US, people can’t seriously discuss “socialism” or “communism” as alternatives without getting attacked and ridiculed (although, according to surveys, most young people in the US are now open to some form of socialism). Leftist movements, when they do arise in the US and Europe, often seem suffused by melancholy, aware of their impotence.

One major problem for the “the Left” and the environmental movement is that they have failed to propose a utopian vision of the future that satisfies people’s deeper yearnings, which are not only logical and based on material concerns, but also emotional and spiritual. Generally, most Leftists are caught in the same naive reductive materialist worldview that underpins capitalism. They see themselves as hard-nosed realists confronting the physical limits of the Earth and the existential condition of a meaningless, accidental universe. They tend to be deeply suspicious of anything like religion, which inspires faith rather than reasoned inquiry.

Acid Capitalism

Recent political theorists, including Mark Fisher and Jeremy Gilbert, surveying the failures of the Left in recent decades, have proposed that the Left needs to return to the countercultural moment of the 1960s and ‘70s. Back then, the Left tried to integrate mysticism, mindfulness, and a “politics of ecstasy” into a political program seeking social and racial justice along with a redistribution of wealth. However, the alliance between the pleasure-seeking hippies and the more dogmatic political activists was always a somewhat uneasy one. These theorists propose a new movement — of “psychedelic socialism” or “acid communism” — as a means to break through the impasse. I think they are on the right track but the model needs development. Above all, the metaphysical argument must be extended much further. I tried to do this with How Soon Is Now (2016), integrating mystical and psychedelic insights into a project for political change and societal redesign.

Decades ago, capitalism managed to absorb the aesthetics and rhetorics of countercultural rebellion into corporate culture and advertising in a way that strengthened the prevailing system (Tom Frank wrote about this in The Conquest of Cool). As an example, philosopher Herbert Marcuse theorized, in the stodgy 1950s, that a liberation of Eros would collapse the old patriarchal structures based on exploitation and domination. However, when the Sexual Liberation of the 1960s and 70s happened, it didn’t topple the system. Marcuse coined the term “repressive desublimation” for what actually occurred. Capitalism assimilated the unleashed libidinal impulses, and became stronger as a result. With the hedonism, licentiousness, and erotic displays of Studio 54 or MTV Spring Break, a limited form of sexual freedom was seamlessly integrated into hyper-consumerism and the prevailing structures of dominance and control.

Part of the extraordinary power of capitalism is its capacity to assimilate anything that might threaten it by revealing something beyond or outside of its reach. The oppositional energy that it assimilates is then transformed into financial value. Che Guevara becomes a t-shirt. Black radical leaders are assassinated in the 60s; a generation later, misdirected anger of black youth is channeled into “Gangsta Rap,” becoming a billion dollar industry. A similar process seems to be happening, right now, with the corporate takeover of the psychedelic experience. It is fascinating — both bizarre and familiar — to witness. But with the ecological crisis brought on by hyper-consumerism, capitalism finally seems to be encountering a limit that it can neither absorb nor escape. So where do we go from here?

Next: Considering Possible Futures: Where do we go from here?

Purchase the seminar here. (Discounts for paid subscribers).

ALSO

Thought provoking as always. Illuminated me, and I ordered two of your books! ✌🏾💗/RBM