This is Part Three of an ongoing thought-stream. Here are links to Part One, Part Two, Part Four, and Part Five.

Before I bring together the lines of thought opened by the first two parts of this essay, I find I must step back for a moment and ask: Do we, in fact, need some kind of radical social change to overcome the current capitalist system, as it is? Or can what we have be repaired, patched up, improved? Some people find the reasons we need a kind of radical transformation quite obvious. For others, it requires a bit of unpacking.

First of all, I am not someone who feels any particular nostalgia about the past. I wouldn’t want to return to an earlier mode, to live without technology, in a completely indigenous way. Yet I recognize that those societies, at their untainted best, provide far more beauty and satisfaction than ours, on many levels, while maintaining a steady-state of harmonic reciprocity with their local ecology. Many intact indigenous cultures possess a satisfying mythos that anchors them in a holistic sense of connection with the Earth and the greater cosmos. These communities tend to possess a greater sense of purpose, meaning, and belonging. I do believe that a future direction for post-capitalist technological society (if there is going to be such a thing) involves learning from these cultures, analyzing their core spiritual, ecological and political principles and translating them into new societal forms.

Three Wounds of Capitalist Realism

Growing up in New York City, I suffered at least three core wounds to my Psyche that I can attribute to “capitalism realism.” These wounds are, I feel, universally shared, collectively painful, and rarely acknowledged. The first was spiritual: I found my innate yearning for meaning and purpose thwarted by my culture’s belief system. Growing up, I learned that we live in an accidental universe where self-consciousness could only be an epiphenomenon caused by the brain’s evolving complexity. Death was permanent annihilation. This was not presented as hypothesis or myth. It was absolute, unquestionable truth.

The second wound was social and political. I didn’t have any sense that I was meant to participate in shaping the future of my society, nor did I feel connected, in a meaningful sense, to any local community. This engendered a sense of alienation and desolation.

Documents written hundreds of years ago established the social contract under which I was destined to live. The United States of America was somehow going to continue “forever” (because this was, after all, “the end of history,” as Frances Fukuyama claimed), following what was writ in those old parchments, which defined our political system, with its two parties. Even though I didn’t feel that either party represented me well, there was never going to be an opportunity to change that. The “Founding Fathers” in their funny powdered wigs were the eternal adults. We were their eternal children.

The third wound was psychological, or psycho-social. Almost everyone I knew, myself included, was the product of broken homes. Our parents’ relationships were either very bad, or our parents were already separated or divorced. At schools, we were not taught techniques for maintaining good relationships or effective interpersonal communication, or how to master our own nervous systems. Such subjects were seen as unimportant compared to memorizing facts about Ancient Rome or learning to solve quadratic equations. TV shows and movies still beamed out the model of the monogamous married couple and nuclear family. This was the great ideal we had to achieve to be healthy and normal, even though hardly any of the adults we knew seemed capable of it.

In our society, extreme wealth inequality, ruthless exploitation of people and nature, property rights (both physical and intellectual), and demeaning, conscripted labor are considered to be normal and inescapable conditions, rather than artificial factors caused by a particular set of social and economic arrangements that we could change.

The pandemic revealed the obvious: Most of the work people do is not necessary for society to function. In fact, the last year could be seen as an experiment in socialism. Masses of people couldn’t work and received unemployment, rents were suspended, and many businesses got loans or pay outs. In theory, the massive debts created will eventually be paid back with interest. In practice, we don’t know for certain this will happen, or if it is even possible.

As political philosophers like Herbert Marcuse pointed out, modern civilization could have made it a goal to significantly reduce the amount of work required of its labor force, liberating people’s time for love, family, self-directed learning, contemplation, and creative pursuits. A rational goal of a post-industrial society would have been emancipating people from drudgery. Instead, capitalism progressed through the imposition of “false needs” and artificial scarcity that generated more capital for the wealthy elite. Even as modern society became more abundant in the 1950s and ‘60s, women were forced to enter the work force (promoted as emancipation). Due to inflationary pressures, where one salary could sustain a family previously, as time went on, even two salaries were hardly enough.

As this video reminds us, the development of technology is not the neutral process it seems to be. It takes place within a capitalist system that needs “planned obsolescence” and waste to incite further production and innovation. To take just one example, back in the 1930s, light bulbs were made that last far longer than a century. Realizing this would put an end to their business model, light bulb manufacturers created a monopoly. Together, they ensured the average life cycle of a bulb would be eighteen months. The same kind of monopoly control in many industries ensures that we do not get access to durable products. It leads to absurd atrocities like the constantly changing cords and headphone jacks for laptops and Smartphones, generating enormous profit on disposable goods that end up in landfills, adding to pollution.

If you like my work, please support it with a paid subscription. Then I can write more, start magazines, and produce podcasts and videos.

What Mark Fisher calls “capitalist realism” — the process of indoctrination that hides the ideology underlying capitalism and makes it seem both natural and inevitable — means that people rarely question either the nature of work in this society or the disposability of its products, which add to the Earth’s ecological burden. Publicly traded corporations are forced, by the monological demands of the stock market, to maximize short-term profits that increase shareholder value. Because of this, they must seek to evade or corrupt costly environmental regulations, while paying their workforce as little as possible. Over the last half century, corporations managed to destroy most of the once-powerful unions and transform the working class (or proletariat) into a “precariat,” with no job security and no stable or assured future. This trend contributes to the epidemic of mental illness we see across the post-industrialized world.

One argument often made by devotees of capitalism is that the value of this system is shown by the fact that it is has lifted billions of people out of poverty, given the multitude unprecedented access to goods and services, and permitted masses of people to lead healthier, longer lives than ever before. This argument is specious on a number of levels. First of all, the fact that there are now billions of people on Earth is a direct result of capitalism and industrial technology which produced the (fossil fuel derived) fertilizer which amped up the food supply, along with so much else. In the year 1700, there were about 600 million people in total on Earth. In 1900, the estimated population was 1.6 billion. Today, it is eight billion. Clearly, it is only because of capitalism and industrialization that there are billions of marginalized people needing to be lifted out of poverty in the first place.

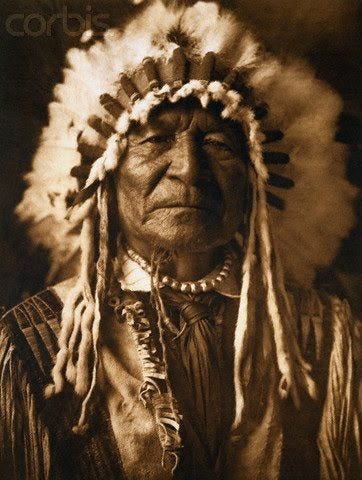

Photo by Edward Curtis

In fact, over the last centuries, capitalism required an ever-expanding population to provide a supply of labor as well as a consumer base for its products. It is also not the case that people outside of the capitalist economic system lived, for the most part, in an abject state of misery. The colonialists who came to the New World were initially astonished by the health and vitality of the indigenous populations, who only seemed to do what they considered “work” (tasks such as hunting, farming, cooking, and weaving) a few hours a day. Possessed by Puritan zeal, the Colonialists found this reprehensible. They took the land away from the original inhabitants, killing those who resisted.

While indigenous populations had a higher rate of infant mortality, beyond the stage of childhood diseases it is not necessarily the case that lifespans were significantly shorter than those of modern people. Some may have lived longer, in fact. History, as we know, gets written by the victors, who often distort evidence to fit their narratives and belief systems.

Also, despite the self-congratulatory bloviations of institutions like The Gates Foundation (funding big-budget NGOs like Global Citizen, which seeks to address poverty without reducing wealth inequality), it is unclear if global poverty has, in fact, been reduced over recent decades or if it has just been pushed further to the invisible margins of the developing world (see Jason Hickel’s The Great Divide for details). Meanwhile as the ecological crisis deepens, global poverty and hunger will inevitably explode, rolling back any progress that was made, as hundreds of millions become climate refugees.

The continuing allure of capitalism is based on an ever-receding set of utopian promises and futurist ideals, many of them based on the shiny promise of technology. The idea that technology was going to emancipate people’s time for free activity, in any positive sense, has proved false. Over the last decades, the utopian hopes for technological liberation turned to the Internet, which was (once again) supposed to emancipate knowledge, time, and creativity for humanity.

We have seen the initial utopian promise of the Internet brilliantly subverted and twisted by the demands of capital. Instead of a free space for humanity to learn and discover, the Internet has become a gigantic surveillance Panopticon with the truly valuable and useful content hidden behind pay walls, replete with “fake news” and “deep fakes” that authoritarian regimes and international crime syndicates weaponize for nefarious purposes, algorithmically driving ordinary people toward fanaticism. The dopamine hits of social media destroy young people’s capacity for sustained concentration and reflection. Once again, capitalist realism has made this all seem somehow a natural and inevitable process, even as the Internet thwarts all of the cherished hopes we once held for it.

Acid Communism

I could continue in this vein but I think that lays out some of the most salient points. I should clarify that I don’t see myself as “anti-capitalist.” I consider capitalism an inevitable stage in humanity’s evolution. As an innately immature, adolescent system, it meshed the world together into one market while forcing incessant growth and over-development.

Concentration of capital inevitably leads to ever-increasing wealth inequality. Capitalism’s growth imperative, if we can’t stop it, will bring about ecological collapse and near-term extinction. For these reasons, we must work together to stop capitalism, even though the system appears invincible. In fact, overcoming capitalism to establish a more equitable and truly rational economic system would, if humans can manage it, constitute something like a collective evolutionary leap forward, from adolescent immaturity to adult responsibility as a species.

Our gigantic problem is that no oppositional group — neither the “Left” nor any “counterculture” — has been able to define a compelling alternative to capitalist realism. (So far, the only proven alternatives are dreadful ones: Religious absolutism or authoritarianism.) This is what Fisher was trying to do, however imperfectly, in the work he was doing before his death in 2017, both in his uncompleted book, Acid Communism, and his last lecture series, Postcapitalist Desire, published posthumously. This is also what I set out to do in my 2016 book How Soon Is Now. In retrospect, that book at the time was “too New Age” to be taken seriously by Leftist academics such as Fisher and his disciples, yet too Leftist/political to captivate New Agers.

These days, the term, “Communism,” is generally considered a putdown, and Fisher uses it partly as a provocation. In Capitalist Realism, he refers to billionaire “philantro-capitalists” George Soros and Bill Gates, prankishly, as “liberal Communists” who believe that the “amoral excesses” of capitalism can be ameliorated through a top-down redistribution of wealth via charity. Jeremy Gilbert, a colleague of Fisher’s, provides this description of Fisher’s concept:

‘Acid Communism’ became Mark’s term for a political sensibility shared by both the psychedelic experimentalists of the counterculture and by the political radicals of the 60s and 70s. This utopian orientation rejected both the conformism and authoritarianism which characterised much of post-war society, and the crass individualism of consumer culture. It sought to change and raise the consciousness of singular people and the whole society, be that through the creative use of psychedelic chemicals, aesthetic experiments in music and other arts, social and political revolution, or all of the above.

Symbols of the late Sixties counterculture such as Woodstock or Haight Ashbury continue to stand for a mythological post-capitalist ideal, defined by cooperation, libidinal expression, community celebration, and shared exploration of psychedelic consciousness. This ideal of a Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ) took a more contemporary form with the Burning Man festival, which started in the 1990s and became a global cultural force over the last decades. I have written about Burning Man elsewhere (in Rolling Stone, ArtForum, and Artsy, among other places). My problem with it is that, as it has matured, it has become something like a countercultural entertainment complex — almost a museum of the counterculture — biased toward Libertarian, rather than socialist / anarchist, ideals. I see Libertarianism as a pernicious ideology, promoting selfish individualism and turning market economics into a religious dogma.

In Acid Communism, Fisher points to the album Psychedelic Shack by The Temptations as an example of how the social utopianism of the late 60s counterculture was spreading across classes and races, with the potential to become a new political force.

What both Fisher and Gilbert propose is that the path forward — toward a more equitable, just, ecologically regenerative post-Capitalist civilization — requires resurrecting the forgotten dreams of the 1960s and ‘70s counterculture, which, at its best, merged political solidarity across classes and races with celebratory movements toward mindfulness and other forms of personal emancipation. This movement sought freedom from hierarchy, degrading work, ownership, traditional relationship models, outmoded religious ideologies, oppressive bureaucracies, and ideological conscription. It sought freedom to participate in the formation of new non-exploitative political and social relations, construct new communities and autonomous zones, and explore the inner dimensions of consciousness via psychedelics, meditation, dance, yoga, among other occult and esoteric practices.

Gilbert makes many crucial points in his essay, Psychedelic Socialism, which I recommend reading. He proposes that contemporary society has — typically — obscured and distorted the original goal of mindfulness practices to mesh with capitalist imperatives and support the hyper-individualist entrepreneur/consumer mindset it engenders. Gilbert writes:

You really would not know from almost any of the literature, institutions or teachers who are busy promoting mindfulness these days, that the aim of this practice in its original monastic context is the complete and total abolition of the individual subjectivity of the practitioner. It’s not supposed to be medicine for the troubled soul, reconciling it to a complex world. It’s only supposed to make you feel better about yourself to the extent that it’s supposed to annihilate your attachment to any sense of self whatsoever. It’s supposed to be a practice engaged in by those who have already renounced all material possessions… its aim is the attainment of that state of enlightenment within which the substantial non-existence of the individual self is fully realised and accepted.

Gilbert is a bit stringent, but his point is a good one. The whole ethos of contemporary New Age spirituality revolves around the concept: Change yourself to change the world. But the observe is equally true and necessary: Change the world to change yourself. You can only change yourself to the extent the world also transforms. Therefore, under the regime of neoliberalism, every technique and practice — even the ontological shock of a profound mystical or psychedelic experience — gets redirected back to the goal of preserving, shoring up, comforting, the individual self. But it is this very self that both Eastern mysticism and Western Communism, from opposite directions, understand to be an illusion.

So what is the alternative? If private property inevitably shores up the illusion of a distinct, separate self, perhaps it is correct, as Marx proposed, to do away with it? In Acid Communism, Fisher quotes the political philosopher Michael Hardt to this effect: “The positive content of communism, which corresponds to the abolition of private property, is the autonomous production of humanity — a new seeing, a new hearing, a new thinking, a new loving.” But of course, any serious inquiry into the abolition of private property as a means for humanity to escape its current cul de sac is out of the question, from the perspective of the current global order. As that exemplar of acid communism, John Lennon, once sang:

I am he as you are he as you are me

And we are all together

But who, today, considers such an insight feasible as a basis for reorganizing social and economic relations?

Up Next: From Capitalist Realism to Anarchist Idealism, Part Four

Part One

Part Two

I’m loving this 6 part series, I recommend Jeremy Gilbert’s books for a deeper exploration of his ideas, Gilbert says the Acid Communism chapter Mark started was heavily inspired by conversations they had both had.

21st Century Socialism & Common Ground: Democracy and Collectivity in an Age of Individualism are both worth reading. Gilbert also has multiple podcasts which are all good - ACFM, Love Is The Answer and Culture, Power & Politics.

I also recommend The New Age of Empire: How Racism and Colonialism Still Rule the World by Kehinde Andrews. A very accessible book on why racial hierarchies and white supremacy are intrinsic parts of capitalism, how it functions and how it was created.

Surely medicine helped populations increase,.stopping filthy sewers and rotten drinking water,.virulent disease?