Analytic Idealism: A Revolutionary New Paradigm

Interview with Bernardo Kastrup for Purple Magazine

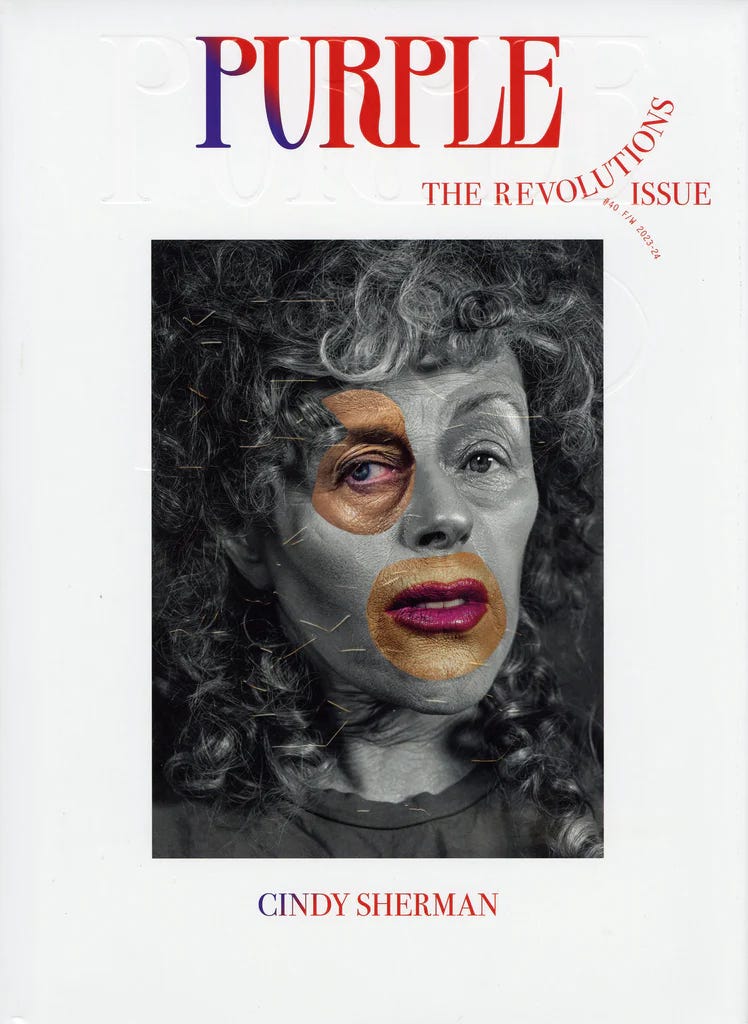

I guest-editored Purple Magazine’s latest issue, with the theme, Revolutions. For the issue, I interviewed Bernardo Kastrup (this was based on my podcast interview, which you can watch here). Hope you enjoy it!

Purple Magazine: Interview with Bernardo Kastrup

If this quantum scientist, philosopher, and computer engineer is right, materialism is becoming irrelevant. His work is nothing short of a philosophical revolution: Called “analytic idealism,” it is radically reshaping our understanding of ourselves and our universe.

It takes time to assimilate Bernardo Kastrup’s philosophy — presented in The Idea of the World; More than Allegory: On Religious Myth, Truth, and Belief; and Why Materialism Is Baloney, among other works — but it is well worth the effort. As an analytic idealist, Kastrup proposes that consciousness is the ontological primitive, the foundation of reality. The entire universe is actually a projection of an indivisible, instinctive consciousness, in the same way dreams are projections of our sleeping minds. Kastrup argues for philosophical idealism in a more comprehensive and logically satisfying way than anyone has recently done before him.

As a scientist who worked at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research), he is well equipped to show how quantum physics meshes with the idealist model. Taking the debate between materialism and idealism to the next level, he proposes, based on the evidence, that “the seemingly objective world we live in is akin to a transpersonal dream: the tables, chairs, stars, and galaxies we perceive within it do not have an existence independent of our minds.” If Kastrup is correct, then the materialist hypothesis is obsolete. His work offers nothing less than a Copernican revolution — a complete overturning — in how we think about ourselves and our world.

DANIEL PINCHBECK — Let’s jump in and tell people a little bit about your history.

BERNARDO KASTRUP — I grew up in the world of science, basically. I went to university at 17. At 22, I had just graduated, and I landed my first job at CERN in Switzerland, in the ATLAS experiment, which has now been running for 10 years, but we were the ones who built it. From there, I went into the high-tech world, doing AI and reconfigurable processors. I have a PhD in computer engineering, but doing work in AI confronts you with the question of what the mind is. Because you build a system that is as clever as a physicist in identifying the detritus that arises from a nuclear explosion or a collision between particles and a detector. So, if it’s intelligent, what is missing to make it conscious, to make its intelligence be accompanied by experience? And I thought about this for a couple of years. I was facing a wall because it becomes clear rather soon that, whatever you do, you’re only changing function and structure, none of which has a bearing on experience. That’s when I realized I was taking a wrong turn somewhere in my line of thinking. I had to trace my steps back and find the point where I was making an unjustified assumption.

DANIEL PINCHBECK — What was this wrong assumption?

BERNARDO KASTRUP — The unjustified assumption, sure enough, was the notion that consciousness is something that is created, as opposed to the field where everything is actually created, where everything actually happens. Once I arrived at this conclusion, there was a journey of a few years to try to reform my worldview in a way that was coherent, internally consistent, and compatible with the empirical evidence, so I would have another narrative in my own mind in terms of which to relate to the world and other people. And the result of that is the philosophy I‘ve been promoting now for almost 15 years.

DANIEL PINCHBECK — I’m curious — in relationship to AI, there was a recent kerfuffle when a Google guy said that his AI had become sentient. You say that if everything is an expression of this unified field of consciousness, then AI is also an expression of that unified field. But I guess the question is whether a part of that structure can become self-aware — and become aware that it has agency and almost has a soul or spirit. Do you think something like that is possible with AI?

BERNARDO KASTRUP — No. I think to maintain that everything is in consciousness does not imply that everything is conscious from its own private point of view. [Holds up bottle] I don’t think this bottle of water is conscious at all. As a matter of fact, I don’t think there is a bottle of water as a proper part of the universe. This is a nominal carving out of the inanimate universe that we call “a bottle” for convenience, but where does the bottle end and the atmosphere begin? Where does the river end and the ocean begin? I don’t think a silicon computer is conscious in the sense of having its own private, conscious point of view, but a computer exists in a field of subjectivity that underlies its own nature. It is an aspect of that field of subjectivity, but it doesn’t have its own private, subjective point of view. I think only living beings have that. I think living beings are dissociated aspects of that broad field of subjectivity, and by virtue of that dissociation, we’ve developed private, conscious points of view.

DANIEL PINCHBECK — So, for you, there’s a firm distinction between living beings and inorganic beings?

BERNARDO KASTRUP — It’s an obvious distinction. It’s because we live in a mechanistic culture that we try to explain everything in terms of mechanistic metaphors, that we fail to see the glaring, obvious difference between inorganic beings and living organisms that metabolize. Metabolism is a very specific, unique process in nature. Protein folding, transcription, ATP [adenosine triphosphate] burning, mitosis — all this is unique to life. And a silicon computer is completely different. It doesn’t metabolize. It’s essentially a glorified calculator. This whole hysteria about AI becoming conscious and uploading your consciousness so you live forever like in Westworld or Ex Machina or Black Mirror — these media products are artificially creating a sense of plausibility for what is essentially absurd. I can run a simulation of kidney function on this Apple iMac in front of me, down to the molecular level. But the simulation is not the thing simulated. When it comes to consciousness, people think that if we simply simulate the patterns of information transfer in a human brain, then the thing will be conscious. That’s akin to thinking that your computer will pee on your desk because you simulated kidney function.

DANIEL PINCHBECK — A feeling that many people have is that AI is continually extending into the domain of activities that we thought were essentially human domains. Many years ago, I interviewed Garry Kasparov, when he was the world chess champion. He was still better than any computer at that time, but he kept looking at the 80-move endgame that the computer had solved, and I think he was suddenly aware that his time was running out. Now you’re seeing, with Midjourney and OpenAI, this sense that even journalism is going to be easily reproducible, potentially, by AI. All sorts of creative activities, music and so on… It feels like there’s this sort of AI shadow hanging over the world.

BERNARDO KASTRUP — I think we make a fundamental conflation. There are two things involved here. One is artificial consciousness; the other one is artificial intelligence. Intelligence is a property measurable from the outside. Intelligence is about clever processing of data and clever decisions about actions to be taken, a way to cleverly react to environmental conditions and environmental challenges. That has nothing to do with consciousness. In our case, consciousness and intelligence come together. If you look at the actual definitions of what we mean when we talk about intelligence, you can have a strong AI, much more intelligent than a human.

I think it’s inevitable. It’s already happening, but that doesn’t mean that such an intelligent computer will also be a conscious computer in the sense of having its own private, subjective inner life. There will be strong AI. What there will not be is artificially created private subjectivity in silicon computers. Consciousness is not something that you can measure from the outside. Consciousness is a type of existent subjectivity per se that I think underlies all nature, animate or inanimate. But private, conscious, inner lives, we have every reason to believe, correlate with metabolism. And nothing else is similar to metabolism, certainly not electronic micro switches opening and closing depending on electron

flow.

DANIEL PINCHBECK — I enjoyed your book The Idea of the World,where you talked about allegory — this view of consciousness as the underlying foundational reality, which understands reality itself as kind of a collective woven dream, in the way poets and mystics have understood it.

BERNARDO KASTRUP — We have this naive view that the world as we perceive it is the world as it actually is in itself. In other words, we think of perception as a transparent window onto the world. We have definitive reasons to know that that cannot be the case. If our inner cognitive state or perceptual states mirrored the states of the world, there would be no upper bounds to our internal entropy, and we would just dissolve into hot soup. Evolution doesn’t favor seeing the world as it is — seeing the truth. Evolution favors survival, so we will see the world in whatever encoded version will distill what is salient for our survival and preserves our inner structure. To put it metaphorically, we are pilots of an airplane that has no transparent windshield. We only have the instrument panel — we are flying by instruments. What we call the physical world is what is displayed on the dashboard of the instruments. We have sensors, like the airplane, that measure the real world out there. In the case of the airplane, it’s an air-pressure sensor, air-speed sensor, and so on. And we have retinas, eardrums, the surface of the skin, the tongue, and the lining of the nose. The results of these measurements on the world as it actually is are presented to us, just like in the airplane, in the form of an internal dashboard that allows us to navigate the world successfully but doesn’t display the world as it actually is. Just like the dashboard isn’t the world outside, the physical world in perception isn’t the world as it is — it’s a representation thereof. And if you accept this, then every facet of the physical world is a symbol on a dashboard; everything is telling you something behind and beyond it. The physical world now denotes and connotes something that transcends the physical world itself, in the same sense that the sky outside transcends the dashboard.

DANIEL PINCHBECK — What’s fascinating about The Idea of the World is that it almost felt like you were proposing a philosophical and scientifically grounded way to reexplore the poetic, symbolic, shamanic imagination.

BERNARDO KASTRUP — Yeah. There are many theories that go under the label of idealism. The only unifying aspect is that all of them state that reality is fundamentally mental. One of the variations that was popular a couple of hundred years ago was Berkeley’s subjective idealism, which can be summarized in the statement, “to be is to be perceived.” And that sort of refines the contents of perception as the thing in itself, and it violates the Kantian dichotomy between phenomena and noumena by basically saying that the phenomena are the noumena. That the world exists only so far as the contents of perception. That perceptions don’t represent a natural objective world outside, that perceptions are the thing in itself. In other words, reality is a kind of a dream, and somehow our dreams are synchronized and coordinated, but there is nothing beyond the images of our own dreams.

I don’t think that is plausible because if you’re sitting next to me, you would describe my study in a way totally consistent with my own description of it. It seems unavoidable that there is a world out there beyond our individual minds. The question is: is that world not mental in essence? Mental processes are out there. The hypothesis of objective idealism is that there is an objective thing out there from our point of view. Just like your thoughts are objective from my point of view, there are the “thoughts of nature” that appear to us upon observation as the physical world of objects and fields and particles, and so on. But from its own point of view, the inanimate world is subjective in essence. In other words, there is a world that doesn’t care what you think about it.

There is a world out there that would still be out there, even if nobody were around to look at it, but it is not physical. Physicality emerges only upon measurement, upon an interaction of a dissociated private mind with these transpersonal mental processes out there. That’s when sensors measure these transpersonal mental processes and display them to an individual mind, on a dashboard in the form that we call the physical world. We preserve the notion of an independent objective world out there that would still be out there, even if there were no private minds to observe it.

DANIEL PINCHBECK — What do you mean when you say that there is no reality and that everything is all mental?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.