Apocalypse, Revelation, Singularity

Excerpt from "Quetzalcoatl Returns"

What follows is an excerpt from my book 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl (recently re-issued as Quetzalcoatl Returns, with an audio version available here). That book explored the prophetic traditions of many cultures, including indigenous people like the Maya and Hopi but also our Western Judeo-Christian tradition. I wanted to pull this section up because I feel the prospect of a technological Singularity, as well as the Judeo-Christian ideas around Apocalypse, are hovering in the background of our current political moment. Certainly, our new unelected “Imperator” Elon Musk as well as his cohort Peter Thiel seek to accelerate and deregulate technological progress, believing we are on the cusp of Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI), which could catapult us into a new reality. In my book, I sought to interrogate this idea of a technological Singularity philosophically, proposing it was based on an obsolete paradigm and ontology. Perhaps this reframing can be useful to us today, as our politics become increasingly psychedelic.

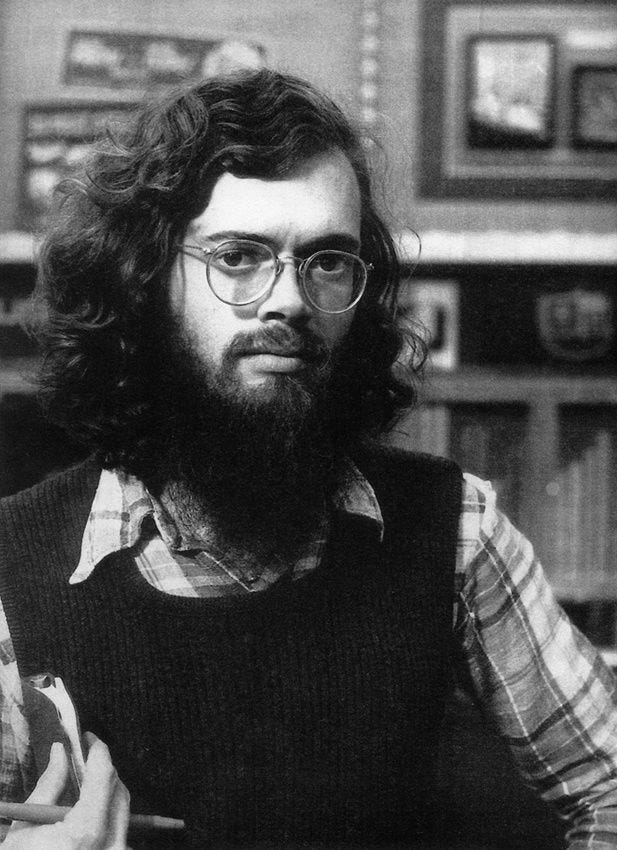

Terence McKenna attained cult status in the 1980s, and his ideas were absorbed into the first flush of technological euphoria that accompanied the dot-com boom. Ultimately, his perspective was Gnostic and hermetic, informed by his psychedelic journeys far more than the Internet. He supported “the siren song of Pythagoras—that the mind is more powerful than any imaginable particle accelerator, more sensitive than any radio receiver or the largest optical telescope, more complete in its grasp of information than any computer: that the human body—its organs, its voice, its power of locomotion, and its imagination—is a more-than-sufficient means for the exploration of any place, time, or energy level in the universe.” Futurist or transhumanist theorists reformulated his vision of an approaching singularity into an imminent “technological singularity,” in which humans will merge with machines in order to transcend our biological limits.

In his essay “The Law of Accelerating Returns,” Ray Kurzweil, author of The Age of Spiritual Machines, examined the exponential evolution of technology, which follows a progression defined by Moore’s Law, and argues that this mathematical growth curve soon reaches a rate of change that is close to infinite. He believes this will occur in this century. “Within a few decades, machine intelligence will surpass human intelligence, leading to The Singularity—technological change so rapid and profound it represents a rupture in the fabric of human history,” exults Kurzweil. “The implications include the merger of biological and nonbiological intelligence, immortal software-based humans, and ultra-high levels of intelligence that expand outward in the universe at the speed of light.”

The futurist theorist John Smart, who operates the Singularity Watch Web site, shares Kurzweil’s euphoria: “Technology is the next organic extension of ourselves, growing with a speed, efficiency, and resiliency that must eventually make our DNA-based technology obsolete, even as it preserves and extends all that we value most in ourselves.” Unlike Kurzweil, who sees humans evolving technologies that expand out to fill up the universe, Smart sees the eventual destiny of the species in what he calls “transcension,” essentially escaping this universe in the other direction, by creating immersive simulations or virtual realities that will be like new universes, drawing all information into the black hole of our information- processing and technology-generating engines.

The transhumanists believe our biological limits should be overcome through mechanical means. We are too dense, too cumbersome in our inherited meatsuits, trapped in what John Smart calls “slowspace.” Immersed in virtual realities or fused with artificial intelligence agents—or some other technological genie—we will attain a speedier, snazzier state of being. Kurzweil notes: “Biological thinking is stuck at 1026 calculations per second (for all biological human brains), and that figure will not appreciably change, even with bioengineering changes to our genome. Nonbiological intelligence, on the other hand, is growing at a double exponential rate and will vastly exceed biological intelligence well before the middle of this century.” By inserting nanobots into our brains or ultimately perhaps down loading our psyches into immortal silicon-based supercomputers, humans will be able to contribute our pitiful little brain-wattage and antiquated personalities to the evolution of A.I.’s higher, faster levels of functioning. Hypnotized by their futurist visions, the transhumanists neglect to note that there is no evidence, as of yet, that machines can attain consciousness.

We should even feel some compassion for the next level of synthetic consciousness we are currently gestating to succeed us. Smart writes: “Consider that once we arrive at the singularity it seems highly likely that the A.I.s will be just as much on a spiritual quest, just as concerned with living good lives and figuring out the unknown, just as angst-ridden as we are today.” Even if, during some hyper-insectile phase of Terminator-style behavior, the A.I.s accidentally destroy the human species, he reassures us, they would no doubt want to re-create us eventually—just as we build museums and zoos to preserve cultures and animals we have made extinct.

The transhumanist vision reflects our cultural fantasies about technology and transcendence, as well as deep anxiety and misconceptions about the essence of time, consciousness, and being. Although not everyone shares the vision of an imminent “technological singularity,” the notion that our technology is evolving in a teleological way toward some ever-approaching yet ever-postponed culmination is endemic to our thinking. It might be that our future lies in an entirely different direction. To see what this direction might be, it is instructive, first, to consider the essential nature of technology.

The philosopher Martin Heidegger noted that the essence of technology cannot be found in any machine or artifact; the essence of technology is the entire “enframing” of reality that is our modern or postmodern worldview. “The threat to man does not come in the first instance from the potentially lethal machines and apparatus of technology,” Heidegger wrote in his essay “The Question Concerning Technology.” “The actual threat has already afflicted man in his essence.” Technology, he notes, is based on an ordering of reality that turns everything—including people—into a “standing reserve,” a resource to be utilized for rationalized ends. The barren architecture of the vast housing projects on the edges of modern cities, where masses of humanity are warehoused as surplus labor, is a natural extension of this worldview.

That more speed, more information, or any form of quantity-based extension or synthetic transcendence of our current human reality is some how valuable, in and of itself, needs to be questioned. An alternative perspective is offered by Eastern mysticism, which has no such vision of progress. As the Hindu guru Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj states in the spiritual classic I Am That: “Get hold of the main thing: That the world and the self are one and perfect. Only your attitude is faulty and needs readjustment.” A faulty attitude creates a faulty world—a world of insufficiency, in which human beings are reduced to the status of things. It is a world of endless distractions, and “distractions from distraction,” where individuals feel like voids that need to be filled. It is a world in which the present is devalued, and our hopes and dreams are projected on an empty future.

Heidegger notes that the origin of the word “technology” comes from the Greek word techne, and this word was applied not only to technology, but to art, and artistic technique, as well. “Once there was a time when the bringing-forth of the true into the beautiful was also called techne,” he writes. “Once that revealing which brings forth truth into the splendor of radiant appearance was also called techne.” He found this to be a numinous correspondence, and considered that, in art, the “saving power” capable of confronting the abyss of the technological enframing might be found.

If art contains a saving power, it is not in the atomized artworks produced by individual subjects, but in a deeper collective vision that sees the world as a work of art, one that is already, as Nisargadatta and McKenna suggest, perfect in its “satisfying all-at-onceness.” Instead of envisioning an ultimately boring “technological singularity,” we might be better served by considering an evolution of technique, of skillful means, aimed at this world, as it is now.

Technology might find its proper place in our lives if we experienced such a shift in perspective—in a society oriented around technique, we might find that we desired far less gadgetry. We might start to prefer slowness to speed, subtlety and complexity to products aimed at standardized mind. Rather than projecting the spiritual quest and the search for the good life onto futuristic A.I.s, we could actually take the time to fulfill those goals, here and now, in the present company of our friends and lovers.

Part of the problem seems embedded in the basic concept of a concrescence or singularity, which compacts our possibilities rather than expands them.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.