Hi People,

Happy Solstice!

It has been nine years since the end of the Long Count Calendar of the classic Mayan civilization. It seems a fitting time to review my wide-ranging book on that topic, originally published in 2006. 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl is now available as an audiobook, brilliantly read by my friend Paradox Pollack. In this edition of my newsletter, I offer a free chapter from 2012 — a long one, and one of my favorites. I would love to know what you think in the comments — and please pick up a copy of the audiobook (50% off for paid subscribers).

Part Three, Chapter Three

Quantum measurements inject our consciousness into the arena of the so- called objective world. There is no paradox in the delayed-choice experiment if we give up the idea that there is a fixed and independent material world even when we are not observing it. Ultimately, it boils down to what you, the observer, want to see.

AMIT GOSWAMI, The Self-Aware Universe

Do places exist on the Earth where the veils separating matter from myth, psyche from spirit, are thin or partly lifted? Glastonbury, England, would seem to be such a spot. The air feels a little different, intangibly charged, as if ancient mysteries were imprinted in the local ether, awaiting the right touch to return to our world. The medieval town also attracts more than its fair share of long-haired louts and lost drunks, as well as spaced-out kids with mangy dogs who come for the annual music festival and forget to leave. They squat in front of the rows of New Age shops hawking mawkish trinkets—crystals, magik wands, tarot cards— insulting passersby, swigging stout, and begging for coins.

Except for its New Age adornments and ruffian factor—also a high local incidence of UFO sightings—Glastonbury and the region around it are remarkably serene and well preserved. Gardening is a popular local pastime; front yards are adorned with shimmering blooms and fragrant blossoms nourished by the abundant rains. I stayed at a bed-and-breakfast three miles from the town center, and enjoyed my daily walk past emerald-green farmers’ fields and cow pastures, keeping my eyes on the Tor, the ancient hump shaped hill and pilgrimage site that looms over the town, topped by a fifteenth-century tower. “There is such magic in the first glimpse of that strange hill that none who have the eye of vision can look upon it unmoved,” wrote Dion Fortune, an early-twentieth-century mystic, founder of the Fraternity of the Inner Light, who lived beneath it. She called Glastonbury “a holy place and pilgrim-way from time immemorial, and to this day it sends its ancient call into the heart of the race it guards, and still we answer to that inner voice.”

Man-made ridges circle the Tor, where cows and sheep often graze, in a spiral pattern. The hill was inscribed with a labyrinth at some distant, long-forgotten point in the past, perhaps thousands of years ago. The path that winds around it may have been used in archaic ceremonies and initiation rites. “There can be but little doubt that the priests of the ancient sun- worship had here their holy place,” Fortune wrote, in her lilting antiquarian style. According to legend, this curiously anthropomorphic mound is a place where the human realm and the spirit world brush each other. “Gwynn ap Nudd, the lord of Annwyn or Hades, was allotted an invisible palace inside the Tor, to which he repaired with his Wild Huntsmen,” wrote the local scholar Geoffrey Ashe in King Arthur’s Avalon. He considered the Tor the probable site of the spiral castle described in the Grail legends. According to local tradition, Morgan Le Faye, King Arthur’s faery half-sister, lived at the foot of the Tor, by a natural underground spring, now a local garden sanctuary called the Chalice Well, providing a counter part of feminine yin energy to the Tor’s masculine yang. The water from the Chalice Well, reddish and iron-tinged, is believed by New Age pilgrims to have mysterious healing properties.

“Behind all the legends, prophecies and revelations at Glastonbury can be discerned one single theme: that the will of God will finally prevail, and humanity will rediscover its natural condition within an earthly paradise,” wrote John Michell in New Light on the Ancient Mystery of Glastonbury. An independent scholar-anthropologist with a large cult following, Michell pursues trails of myth and geomancy leading from ancient paganism and neolithic lore to the establishment, according to legend, of the world’s first Christian Church at the site of Glastonbury Abbey by St. Joseph of Arimathea, meshing with medieval fables of King Arthur and the Grail.

For archaeologist Philip Rahtz, such “alternative archaeology” has turned the so-called “Sacred Isle of Avalon” into “the Mecca of all irrationality,” attracting “an incredible variety of hippies, weirdoes, drop-outs, and psychos, of every conceivable belief and in every stage of dress and undress, flowing hair and uncleanliness.”

The morning after I arrived, I took a bus tour to visit a few crop circles, some of the newest and best of the season. The tour guide on our bus, David Kingston, a polite gray-haired man in his sixties, dated his involvement with the phenomenon to the 1970s, when he worked in British military intelligence. In 1976, he was part of a group investigating UFO activity in Wiltshire. One night, stationed atop a hill, he watched six or seven “spheres of light” hover in the air, then merge into one long sphere. The long sphere ascended to the height of the stars, then blinked out. “At day light, we found a straightforward circle, thirty feet in diameter, in wheat,” he recalled. He went on to give a short history of the phenomenon since that point. He was especially interested in shifts in the magnetic fields around formations, and the discovery that particular glyphs emitted high- pitched sounds. “Quite often, we don’t hear anything by ear. We pick it up by machine, and analyze the sounds later.”

The first crop circle we visited had just appeared the day before. Our guide passed around the bus a photograph of the formation, taken by airplane. On one level, the formation showed a tree bearing a large number of round fruits, its roots spreading out in a fan shape beneath it. However, the image could also be read as a mushroom—not just any fungus, but the Fly Agaric or Amanita muscaria, the red-and-white-spotted visionary sacrament of Siberian shamanism. When the image was flipped upside down, the underside of the “tree” appeared as another mushroom—the roots turned into the small ridges or gills of the classic Psilocybe cubensis, the “magic mushroom” used in South American shamanism, also prevalent throughout England and Ireland.

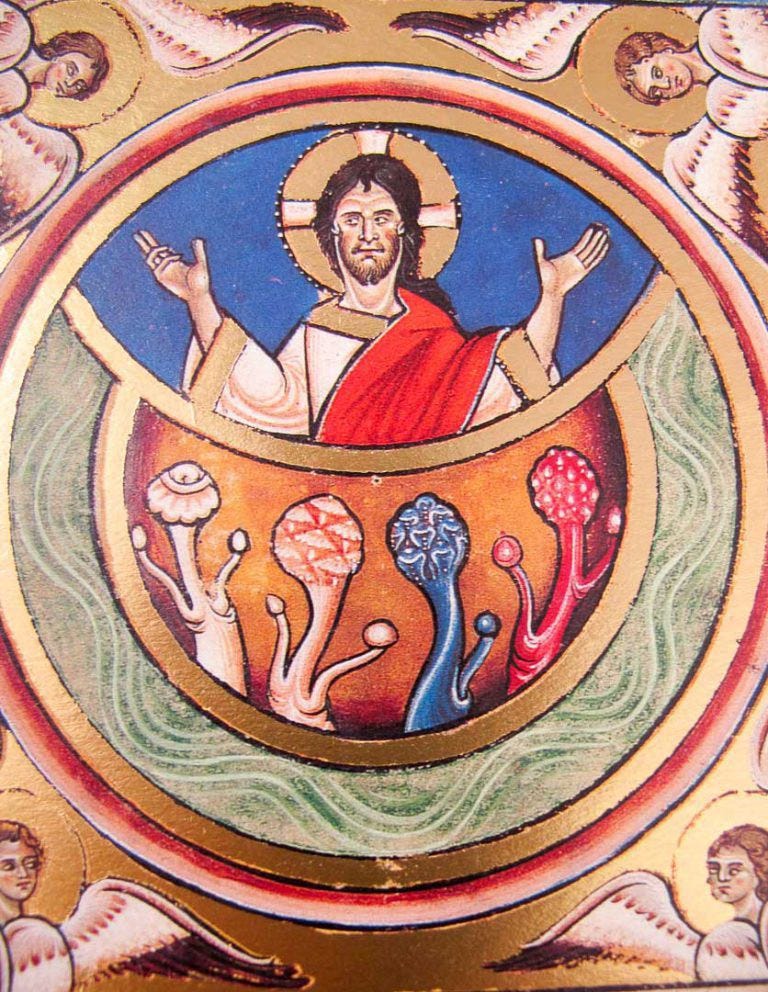

In Breaking Open the Head, published later that year, I discussed a scholarly dispute over these two species of fungus, both considered candidates for the original Soma, the visionary intoxicant or entheogen described in the Rig Veda as a milky liquid pressed from a plant. Although its nature is long forgotten, Soma was the archaic catalyst of Hindu cosmology. The banker and mycologist Gordon Wasson—rediscoverer of the mushroom cult of the Mazatec in Mexico in the early 1950s—argued that amanita was the mushroom used by the Hindus. Terence McKenna countered that Soma was most likely a species of psilocybin-containing fungus. McKenna theorized that psilocybin, not Amanita muscaria, sparked human language development, and was the lost dispenser of “vegetable gnosis” at the heart of most world religions. In one hieratic icon, the double—or triple—reading of the crop glyph suggested all of these Gnostic possibilities.

I also noted the thesis that early Christianity concealed a secret cult devoted to Amanita muscaria, developed in the 1970s by Princeton art historian John Allegro, in The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, a controversial work. This idea was recently revived by the Italian scholar Giorgio Samorini, who assembled images of frescoes from early Christian churches in support of Allegro’s thesis. Some of these pictures, dating back to the second or third century AD, showed a plant that would be recognized as a Tree of Life by churchgoers, or as an amanita by initiates into the Mystery. An entire lexicon of hermetic imagery and psychedelic scholarship had been artfully evoked and skillfully compressed into a single glyph imprinted in Wiltshire wheat by unknown perpetrators.

There also seemed the suggestion of a figure in the formation, hanging upside down from the tree. As the glyph related to shamanism, this figure suggested the Norse god Odin, or Votan, a prototypical shamanic figure. Odin hung from Yggdrasil, the World Tree, for nine days, in order to achieve knowledge of his own fate and the fate of his fellow Norse gods. During that time, he learned that the gods were going to perish during Ragnarok, a final struggle with their titanic foes. For Odin, it was a lesson in humility, forcing acceptance of the inescapable shape of fate. The World Tree is a universal shamanic symbol, representing the various levels of being traversed by the shaman, from the underworld to the realms of the gods.

The Tree of Life crop circle was in Adam’s Grave, a few miles from the stone circles of Avebury and the peculiarly tit-shaped man-made mound of Silbury Hill. We parked the bus and walked out into it—the Glastonbury conference had made deals with local farmers, paying them in advance for access to their fields. Farmers in the area run the gamut in their response to the formations—some try to exploit the phenomenon, others cut out the patterns as soon as they appear, or bar visitors access to the land. Still others superstitiously tolerate them. We followed arrows into a field not too far from the road. The gold-colored grain came up to my waist, tickling my arms. It was a beautiful, sunny day.

The formation was over three hundred feet long, and it had been executed with exactitude. There was a little pip at the center of each fruit dangling in the tree’s branches (or each spot on the amanita). In the field, this effect was produced by taking the central clump of standing wheat stalks and twirling them around—it was difficult to see how hoaxers would have accomplished this, so elegantly, in darkness. On the ground, the crop had been laid down in careful patterns, in some places designed to create a three-dimensional effect. Each of the thin—perhaps foot-wide—lines of fallen wheat making the ridges that appeared as the roots of the tree, or the gills of the mushroom, had been toppled in the opposite direction from the ones next to it. The crop appeared to have been knocked down by a compressed force of some kind, in one fast and precise movement. There did seem to be an energetic charge within the formation—I felt, almost, as if I were tripping. I had the impression of an invisible eyeball suspended over head, as Terence McKenna noted in the Amazon, “something in the sky, calmly omniscient but closely observing us.” Many of the people in our tour group quickly sank to the ground. Falling silent, they assumed meditation postures, or lay flat on the fallen wheat. This reaction is typical, almost non-volitional, in new formations.

As I wandered the pattern, crushing the fallen stalks underfoot with each crackling step, I met a young bearded man with an ascetic, intelligent face, who seemed to be examining the lay of the crop with a certain casual expertise. We started talking, and I learned he was one of the presenters at the 2002 Glastonbury Crop Circle Conference, which I was attending over the weekend. His name was Allan Brown. He was just driving from his home in Brighton to Glastonbury, and he happened to see this formation from the side of the road. Coincidentally, he had been listening to a recording of McKenna while he was driving. He had not yet seen a picture of the formation from above. I told him my double mushroom interpretation.

“I find the crop circles to be a very psychedelic phenomenon,” Allan said. We discussed our admiration for McKenna’s work. He told me he was staying with Michael Glickman, the crop circle researcher who had talked about the “dimensional shift.”

We walked over to a middle-aged woman in an embroidered blouse who had taken out a dowsing pendulum, a pointed rock crystal dangling on a chain, and was testing various spots inside the crop circle. Dowsing is traditionally used to find sources of water underground, and its utility for that purpose is generally recognized, but it has also become popular among followers of the New Age as a way to trace patterns of energy and discover “ley lines,” mysterious currents of geomantic energy. The historian Ronald Hutton dismisses this interest in energy patterns and geomantic currents as “a modern mythology.” He notes, “During the last twenty years, thousands of hitherto unsuspected prehistoric monuments have been rediscovered by means of geophysical surveys and aerial photography,” yet “not one has been found by all the psychics and dowsers who abound in ‘alternative’ archaeology.” I asked if I could try the pendulum for a moment. Holding it still, I noted that the crystal was definitely pulling at a strong angle, perhaps indicating an alteration in the magnetic field beneath the formation.

We left the World Tree and drove to a second glyph that had appeared a few weeks earlier, on July 4, 2002. If anything, it was more extraordinary— certainly more beautiful—than the tree formation. This crop circle was only a short distance from Stonehenge, and for the first time, from a distance, I saw that ancient monument, its ragged obelisks encompassed by tourist throngs, as we exited the bus, filing across another farmer’s land. The pattern showed a vine with leaves along it, forming six symmetrical loops in an oval shape. Over 450 feet long, this crop circle made impressive use of the landscape, skirting the edges of three Neolithic barrows. Earth-covered hillocks made of stones, originally tombs or initiation chambers or both, these barrows dot the lands around Stonehenge and Avebury. If this crop circle was crafted by humans, a global positioning system must have been used, or some other land-surveying technique at a high degree of accuracy.

Returning to Glastonbury at dusk, I hiked to the top of the Tor to watch the sunset, a harmonic orchestration of silvery slivered clouds and fading purple hues. From the Tor, I had a panoramic overview of the region’s green rolling hills and fields. Much of the area was originally underwater, in marshy peat bogs, dredged over the course of centuries yet retaining its fertile lushness.

When I tried to sleep that night, I was kept awake by hypnagogic visions that continued until dawn. I observed a misty parade of creatures— gaudy, gauzy entities that could have marched out of the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. They waved banners and staves and strange spiky things. I awoke many times, peering out my curtained window over moonlit fields, and when I tried to sink back into sleep, the flickering festival started up again behind my closed eyelids.

Ever since my DPT experience and other shamanic forays, I had accessed an occasional visionary capacity beyond my ability to control. From time to time, interior images or scenes appeared spontaneously, projected by my third eye, without any psychedelic catalyst. Buddhist philosopher Ken Wilber, much given to defining the evolution of consciousness and ingression of “spirit” in endless levels and ladders and graphs, noted that “psychic facts” became evident in the “psychic worldspace” at a certain level of development, which he called “vision-logic.” Wilber proposed that these “psychic facts” were just as apparent as the material things in the physical world, once you were able to see them. Something like this had happened to me, if I understood it properly. The other option, of course, was that I was sliding down a slippery slope toward an unusual form of madness.

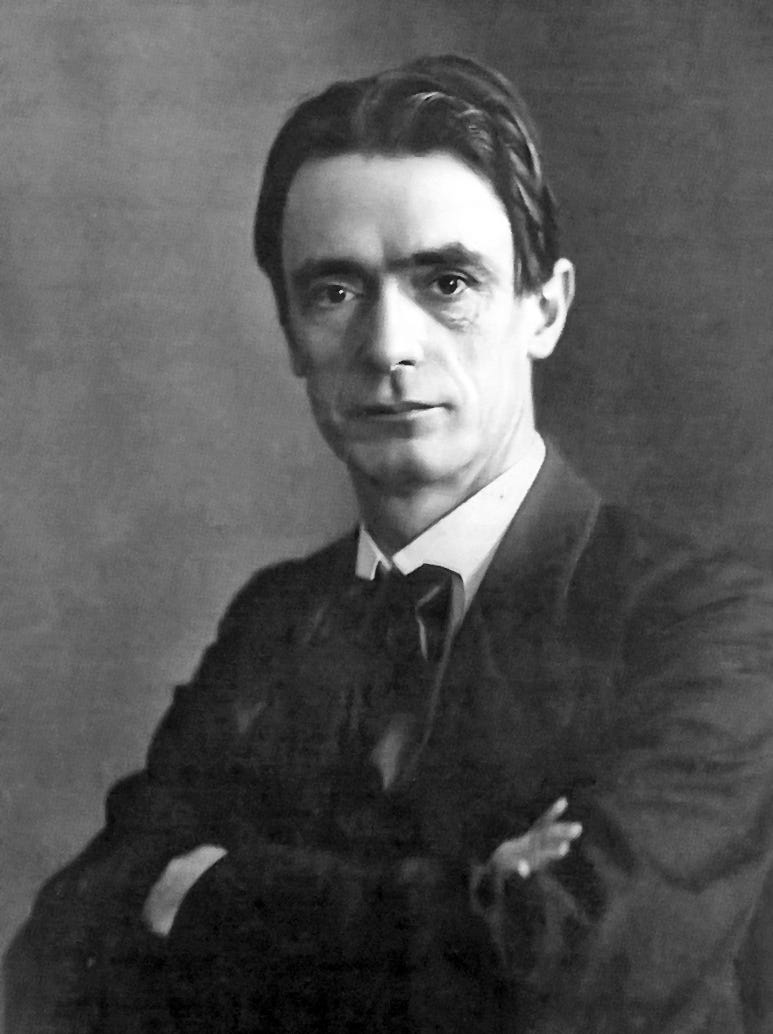

To my surprise, the thinker who gave me the deepest insight into my new situation, rescuing me from an acute occult crisis, was Rudolf Steiner, best known for creating Waldorf Schools and biodynamic agriculture, a forerunner to today’s organic farming. Despite these achievements, a fusty ambience of Victorian dustiness surrounds Steiner, whose works are rarely read outside the Anthroposophic movement he founded over a century ago. Steiner is vaguely associated, in the mainstream mind, with fringe movements and mystics such as Emanuel Swedenborg and Madame Blavatsky— his image is of a vaguely sentimental sanctimony and old-fashioned Christian rectitude. Some confuse his movement with the Amish. This dour reputation is tragically undeserved and absurdly off the mark.

When I discovered Steiner, I was amazed by the exalted quality of his thinking—opening onto vast new realms of visionary possibility—and his deep humanity. Against the materialist tendencies of his age, he proposed a “spiritual science” as rigorously grounded as any of the natural or behavioral sciences, but based upon “supersensible” perceptions, attained through an evolution of our cognitive capacities. “Spiritual science attempts to speak about non-sensory things in the same way that the natural sciences speak about sense-perceptible things,” he wrote. He argued that it was a prejudice of materialists to believe that the form of empirical cognition they practiced was the only legitimate means of approaching reality. “No one can ever deny others the right to ignore the supersensible, but there is never any legitimate reason for people to declare themselves authorities, not only on what they themselves are capable of knowing, but also on what they suppose cannot be known by any other human being.”

He argued that the development of the modern consciousness, with its individuated and alienated ego, concealed a higher purpose. Although our civilization cut itself off from spiritual knowledge, we have the free choice, as individuals, to seek it out, through our own efforts. Our empirical and analytical mind-set provides a firm basis for exploring supersensible realms— if we reorient ourselves toward this different goal.

Steiner prepared the philosophical ground for exploring what he called “higher worlds,” carefully describing the stages in acquiring visionary modes of perception, as well as the dangers one might encounter along the way. One can learn to attune one’s self to the threshold of the sensible, using the psyche like an antenna for subtler perceptions and secret revelations. This effort of esoteric training requires a development of the whole person, in separable from moral progress. The use of psychedelics seemed a faster but less conscientious means of attaining supersensible insights, perhaps through stimulus of production of DMT in the pineal gland.

Once he laid the groundwork, Steiner proceeded to explore cosmic domains beyond anything I had encountered before, or conceived as possible, elaborating a vast hierophany. Studying him, I felt I had found a comprehensive alternative to modern rationalism—and one that offered tremendous hope and shining inspiration. He reclaimed the occult traditions that the modern world had forfeited, within an ethical framework. His perspective incorporated the empirical methods of science, and transcended it.

Terence McKenna later suspected that the episode he and his brother had in the Amazon had occurred due to their immersion in visionary realms, coupled with a willing suspension of disbelief. “One reaches through to the continents and oceans of the imagination, worlds able to sustain any one who will but play, and then lets the play deepen and deepen until it is a reality that few would even dare to entertain.” He proposed “that the human imagination is the holographic organ of the human body, and that we don’t ‘imagine’ anything. We simply see things so far away that there is no possibility of validating or invalidating their existence.” Walter Benjamin, similarly, thought the imagination was like a fan that could be opened infinitely, unfurling vast Proustian vistas in the smallest moments of perception. Steiner systemizes this understanding, proposing imagination, intuition, and inspiration as three modes of visionary cognition that can be developed through intense discipline.

Where Western philosophers such as Immanuel Kant believed there are “things in themselves” separate from our perceptions of them, Steiner noted that such a division can’t be maintained. To separate thoughts from the “things in themselves,” to alienate matter from mind, is already, always and only, a thought—therefore it lacks intrinsic validity. Thinking is an aspect of reality—as much a part of the world as any physical object or process—and cannot be amputated from it. “Doesn’t the world bring forth thinking in human heads with the same necessity that it brings forth blossoms on the plant?” he asked. Carl Jung—who also realized the reality of the psyche—thought the mythic archetypes contained in the psyche had autonomy and agency beyond the individual. Similarly, Steiner proposed that thinking, in itself, was neither objective nor subjective, but universal. “In thinking we have that element given us which welds our separate individuality into one whole with the cosmos. In so far as we sense and feel (and also perceive), we are single beings; in so far as we think, we are the all-one being that pervades everything.” In our feelings and perceptions we are separate, but our thinking connects us to the larger community of mind—what Teilhard de Chardin dubbed the noosphere.

If we conceive of thinking as a part of the world, inseparable from natural processes, then there can be no limits to our cognition. Thinking is not a passive tabulation of objective facts, nor can science lead to a definitive “final theory” about the universe. Thinking becomes, instead, a creative and participatory act that transforms reality. In Steiner’s science of the imagination, philosophy becomes the art of reconciling “percepts”—those entities and things we perceive outside of ourselves—and “concepts”—the elements of our cognition. There can be no conceivable end point or limit to this work of reconciliation. It is an infinite task—an infinite play. “All real philosophers have been artists in the realm of concepts,” he wrote. I found Steiner’s perspective to be shockingly liberating. He offered a non- dualistic revisioning of reality.

Steiner was compelled to develop his philosophy out of his circumstances and unique gifts. He was born in Kraljevec, on the border between Hungary and Croatia, in 1861, of Austrian parents. His father worked for the Austrian Southern Railway, and was promoted to the job of station master at Pottschach in Lower Austria, where Steiner grew up in modest circumstances. As a child, he was a natural clairvoyant—he could perceive the beings, energies, and fluctuating patterns of the supersensible realms, as well as the spirits of the dead. In his memoir, he recalled how a relative from a distant town appeared to him one afternoon, asking him to take care of her where she was going. He later learned she had died that day. Such episodes are common in indigenous cultures, where the shaman is known to act as the intercessor for the dead—in our modern world, they are seen as aberrations of mental illness.

Since those around him did not possess his clairvoyant powers and didn’t understand them, Steiner learned to be quiet about his gifts. At the same time, he kept trying to understand the barriers that prevented people, not only from attaining supersensible perception, but even from being able to conceive that anything like it might exist. He felt a great sense of relief when he encountered geometry in school, which introduced him to a realm of pure mental forms resembling some of his inner visions.

Realizing that he needed a training in philosophy if he was going to convey the hermetic knowledge that was freely available to him but hidden from others, he completed his doctorate at the Vienna Institute of Technology, then took a position editing Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s science papers, moving to Weimar in Germany. In the work of the great Romantic poet and scientist, Steiner found a theory of knowledge that supported his supersensible investigations. While living in Weimar, he visited Friedrich Nietzsche, who had already lost his senses and was confined to his bed. Steiner described seeing the soul forces, depth of spiritual longing, and supersensible beings that had animated Nietzsche’s tragic quest for knowledge. He later wrote a book about the philosopher, calling him a “fighter for human freedom.”

At the age of thirty-six, Steiner moved to Berlin to work as editor of the Magazine for Literature, a literary journal. In Berlin, he became part of a bohemian cultural milieu that included the writers Frans Wedekind and the literary bon vivant Otto Erich Hartleben. He found that the writers and artists in his circle were so obsessed with aesthetics that they cut them selves off from the living processes of the world. “Even very fine people— even those of distinguished character—had an interest in literature (or painting or sculpture) so deeply ingrained that the purely human element completely withdrew into the background.” Steiner perceived his connection to these artists extending back to past incarnations. Their character flaws were the “results of previous earthly lives, which could not be fully resolved in the cultural environment of the present life. It became clear that future earthly lives were needed to transform those imperfections.”

With admirable patience, he waited until he was forty years old before he began to speak in public about his visionary knowledge, sharing the astonishing cosmology he had developed through painstaking investigation of his inner world. Steiner claimed to have access to the “Akashic Record,” a spiritual imprint of the evolution of humanity, from distant past to far- flung future. According to occult philosophy, the Akashic Record becomes available to clairvoyants at a high level of attainment; in the United States, the twentieth-century mystic Dr. Edgar Cayce was famous for his ability to access this “library” while in trance states, recounting past incarnations of his patients and prescribing cures for them. After Steiner went public with his supersensible knowledge, he published dozens of books and gave over three thousand lectures during the last twenty-five years of his life, establishing anthroposophy as a “white occult” movement to oppose the negative occult and nihilistic trends he saw around him, which would culminate in the rise of Hitler’s Nazi Party, its diabolical delusions of Aryan purity leading to global war and the Final Solution.

I would not have been receptive to Steiner’s cosmological frame if it weren’t for my own shamanic journeys, which seemed to open doorways in my psyche that never completely closed. In the vast ecology of mind he describes, our consciousness is inseparable from other forms of sentience— such as the goblins, or postmodern Grays, who swarm us as we pass between sleep and dream. Steiner split up the unitary Christian devil into different forces that constantly work upon the human psyche, seeking to divert us into deviant paths. Lucifer, the “light-bringer,” draws us upward into realms of imagination, beauty, fantasy, and egoistic pride, pulling us away from the Earth. The other power is Ahriman, dark and malevolent Earth spirit of the Zoroastrian faith, also known as Satan, Mephistopheles, and Moloch. Ahriman drags us downward—into the mineral world, materiality, mechanization, and death. Our age of materialism represents the temporary ascendance of Ahriman, who strives to make the world into a machine. Studying Steiner, I recognized Lucifer and Ahriman as “psychic facts,” part of the wallpaper of my new “psychic worldspace.”

The occult hangover of my DPT trip seemed, intuitively, a kind of psychic combat, ending with the integration of my shady nemesis or dream daimon. Afterward, I felt significantly sharper, though this sharpness was double-edged. I had to recognize and learn to resist the tendency to feel contempt for the lumbering crudity of our human world—contempt for my own shortcomings, as well. For months I felt as if an invisible snicker or sneer was suspended over my head. In Steiner’s work, I encountered detailed descriptions of the Luciferic forces, the “sceptered angels . . . spirits reprobate” crowding the pages of Milton’s Paradise Lost. According to Steiner, these entities were not evil, but deviant. They were far more advanced than humanity in many ways—too advanced to take physical incarnation in our world—yet they required us as the ground for their further development. Luciferic spirits seek to “take refuge in a kind of substitute physical body,” by making an alliance with a human being who has passed a certain threshold of psychic development. “We are the stage for the Luciferic evolution,” Steiner notes. “While we simply take the human earthly body in order to develop ourselves, these Luciferic beings take us and develop themselves in us.” He cited Romantic poets and Baroque composers as examples of men who had made temporary alliances with Luciferic forces. I sensed he was also describing what had happened to me.

Lucifer is mocking and outraged, caustic and impolite—like some debauched, Dionysian rock star of the late sixties, he wants the world, and he wants it now. The Luciferic tone is perfectly embodied in the works of Aleister Crowley, the self-proclaimed “Great Beast” of modern magic, who apparently entered into a daimonic alliance. As he recounts the story, Crowley received a channeled text, The Book of the Law, in Cairo, in April 1904, after a number of synchronicities and magical manifestations, and a night spent with his mistress in the Great Pyramid’s central hall. For one hour at a time, over three days, a voice spoke in his head, dictating the work—according to Crowley, its validity was proved “by the use of cipher or cryptogram” relating “some events which had yet to take place, such that no human being could possibly be aware of them.” The voice identified itself as Aiwass, a disembodied intelligence—“a messenger from the forces ruling this Earth at present.” The transmission reads like a histrionic work of late Romantic poetry—and much like the rhyming reams of mediocre verse produced by Crowley himself. Aiwass’s The Book of the Law samples Swinburne, Nietzsche, bits of Blake, expressing a streak of maniac cruelty:

We have nothing with the outcast and the unfit: let them die in their misery. For they feel not. Compassion is the vice of kings: stamp down the wretched and the weak: this is the law of the strong: this is our law and the joy of the world. Think not, o king, upon that lie: That Thou Must Die: verily thou shalt not die, but live.

Utterly convinced by this episode, Crowley believed himself chosen to be the messiah and prophet of the New Aeon. He called himself “the Master Therion, whose years of arduous research have led him to enlightenment.”

Crowley spent the rest of his life following The Book of the Law, including its call to immoderate excess.

To worship me take wine and strange drugs whereof I will tell my prophet, & be drunk thereof ! They shall not harm ye at all. It is a lie, this folly against self. The exposure of innocence is a lie. Be strong, o man! lust, enjoy all things of sense and rapture: fear not that any God shall deny thee for this.

In Jungian terms, one might say that an archetype, an immaterial cluster of psychic energy—“spontaneous phenomenon” with “a certain autonomy,” according to Carl Jung—attempted to constellate in Aleister Crowley: the archetype of the “Great Beast 666” from the book of Revelation. The “Great Work” Crowley believed he would accomplish did not come to fruition in his lifetime. Seeking to overcome the Victorian repression of sexuality and the body, Crowley, “the prince-priest the Beast,” indulged in techniques designed to shock and offend. Crowley borrowed ideas from the Eastern disciplines of Tantra, esoteric practices in which the desires and passions of the sensory world are used to attain liberation. He debased these ideas into a system of “sex magick,” in which sex acts, including homosexual intercourse, are a means of initiation into endless hierarchical stages with pompous titles. Instead of an achieved Tantrism, his life’s work was an extended tantrum. If Crowley made a daimonic alliance, it intensified his ability to produce psychophysical phenomena, as described in the many accounts that embellished his legend. But the alliance magnified his character defects, leading to his ruin.

The glamorous ego-inflation of Lucifer is countered by the mechanistic deflation of Ahriman, who reduces humans to the status of things, a “standing reserve” to be used for inhuman ends. The techno-futurist fantasies of transhumanists in which artificial intelligence takes over, science fiction such as RoboCop and Terminator, the sociobiological perspective of books such as Guns, Germs, and Steel and The Selfish Gene, the glacial technological predation of the alien abduction accounts—such artifacts reveal Ahriman’s one-dimensional viewpoint, which reverberates through our culture.

Steiner did not believe it was possible to separate ourselves from these influences—like Jung, he considered the “devil” a psychic reality that had to be assimilated into consciousness, rather than rejected or repressed. In Steiner’s view, humanity walks a balance beam between these opposing forces, and Christ’s sacrifice gave us a model for maintaining the necessary equanimity and deep humility that our position requires. Since Moloch rules the roost in our current world, Steiner believed that we needed to recover the Luciferic influence to counteract him—he titled his anthroposophic journal Lucifer Gnosis. I suspect that Steiner would have seen psychedelics as Luciferic catalysts, helping us access lost modalities of supersensible perception, but possessing the danger of deluding us with hubris, leading us away from earthly responsibilities.

In certain hermetic traditions, the Holy Grail is described as “a jewel that fell from Lucifer’s crown”—one of the myriad meanings circling around this ancient palimpsest. The jewel in Lucifer’s crown refers to the third eye—pineal gland or ajna chakra—located in the middle of the forehead. The opening of the third eye brings about spiritual vision, supersensory perception—unless you are the Hindu god Shiva, who destroys the manifest universe when he opens his third eye, at the end of a kalpa. For those who are unprepared, like the mind-blown hippie masses in the back ground of the film Altamont, this opening leads to disorderly hallucinations and an unmooring from reality. In supersensible domains, according to Steiner, the individual psyche shapes what it beholds, magnifying neurotic disorders into phantasmagoric horrors. To approach the supersensible world in a healthy way requires inner strength, patience, and calmness. “Our reasoning must be perfectly lucid, even sober, at all times,” Steiner warned.

THE STEINERIAN VISION seemed particularly appropriate to Glastonbury; the Holy Grail is one of many legends blanketing the region like morning fog. According to legend, St. Joseph of Arimathea, the disciple of Christ who took Christ’s body down from the Cross, was instructed by an angel to take his followers to England, bringing with him two “cruets” containing the blood and sweat of Jesus. After a long and arduous journey, they landed in Glastonbury. They were given permission by the local king to found a community in the area. They built their simple huts of wattle and mud and a modest wooden church on the spot where the powerful Glastonbury Abbey was later founded.

It is impossible to determine whether or not this story has any validity. However, there is evidence supporting it and none contradicting it. When he and his disciples first docked, St. Joseph is said to have planted his staff, which came from the branch of a thorn tree, near the top of Wearyall Hill, the second highest promontory in the area. His staff took root, and a single specimen of a type of thorn tree native to the Middle East still grows there today. Another tree of the same species spreads its gnarled charm in the garden at the abbey. The abbey thorn tree blossoms once a year, around Christmas, and a sprig of its flowers is placed on the queen’s breakfast table every Christmas morning.

Whatever its origins, the Abbey of Glastonbury was the center of English Christianity for many centuries, until it was smashed up and burned to the ground by King Henry VIII in 1539, its last abbot executed on the Tor. The abbey’s ruins display a number of stone structures that must have been formidable Gothic edifices—perhaps even more beautiful as jagged vestiges. According to tradition, the monks of the abbey were able to hide many of the abbey’s treasures and manuscripts in secret troves around Glastonbury—still awaiting rediscovery, according to local lore. Beneath the wrecked abbey, secret underground tunnels are said to exist, snaking to neighboring valleys and villages, built by the monks to escape Henry’s wrath.

The “mysto steam” rising from Glastonbury kept affecting me. On a break from the conference in Glastonbury’s town hall, I visited the abbey for the first time. Sitting near the center of the old church, before a stone slab commemorating the spot where King Arthur and Guinevere’s tomb was discovered in the twelfth century—an event generally dismissed by mainstream historians as an early prototype of the modern publicity stunt— it was easy to close my eyes and catch a momentary, flickering vision of a white-robed ceremony or coronation, presided over by faint hooded figures. Was I sensitive to some energetic trace or psychophysical imprint left in the area, or was I prey to suggestibility that brought these images, unbid den, into my mind-screen?

The Crop Circle Conference consisted of an enjoyable series of talks given by a range of eccentric characters, including local celebrities and best-selling scholars on the alternative archaeology circuit. It was held in the town hall, in a large auditorium decorated with wildly colorful murals that jumbled crop circle symbols with Egyptian, Mayan, and outer-space iconography. While some talks focused on the formations, others explored loosely connected areas such as the Qabalah, ley lines, the conspiratorial secrets of the Bilderburg Group and the Trilateral Commission, and the methods of divination used in ancient Greece. My new friend Allan Brown spoke about some of the ways in which the crop circles seemed to be reawakening knowledge of the ancient Neolithic landscape and culture. Following clues provided by some of the patterns, he thought he had found the outlines of huge ancient goddess figures indicated by natural and man-made landmarks across Wiltshire. “The whole landscape was a living ritualistic expression, designed or encoded during the Neolithic Golden Age,” he theorized.

A star of the conference was Michael Glickman, a charming man in his sixties with a short salt-and-pepper beard and large, expressive hands. Suffering from multiple sclerosis, Glickman walked with two canes, yet his handicap did not keep him from the center of the action. When I had interviewed him from New York, Glickman said that researchers into crop circles split into two camps—seekers after mechanism, or seekers after meaning. “I consider myself to be a seeker after meaning,” he said. Because of his willingness to go out on a limb, Glickman was a favorite target of skeptics and hoaxers.

In his lecture, which he delivered in a tuxedo—a pointedly grandiloquent gesture, indicating his own sense of possessing elite knowledge, against the ignorance of the masses—Glickman theorized that the crop circles were giving hints of an accelerated process of psychic transformation. In our daily lives, we were also getting cues that we were on the cusp of this new world reality. These cues were being given “so gracefully, so respectfully and so gently” that you had to attune your mind to them, or you would miss them. Glickman listed a number of “signs of the dimensional shift.” These included the experience of time speeding up; an increase in synchronicities and coincidences; acceleration of premonitions and intuitions; and the occasional occurrence of “little light events without a source,” demonstrating “Newtonian mechanical impossibility” or violations of probability—he showed a slide, taken by a friend of his, of a herd of sheep forming a perfect circle in a Scottish meadow, for no discernible reason. He also thought the “karmic elastic band is snapping back faster and faster,” with rewards and punishments meted out almost instantly.

“Thoughts seem to be effecting reality more than before,” Glickman conjectured. “The universe is increasingly obedient, compliant, even dumb.” The formations depicting different kinds of fractals displayed an essential truth of the universe: “Everything is everything. Everything contains everything. Everything is part of everything else.” He showed a slide of one enormous crop circle that had flattened hundreds of feet of crop in all directions, but left one ignominious thistle bush standing, exactly at the center of one of its spokes. “This whole enormous feat was organized around this one modest plant,” he said. “The circlemakers are showing us their reverence for other life forms.”

The gigantic thirteen-armed spiral formation of 409 circles that appeared on Milk Hill in August 2001 represented “the hinge point of the dimensional shift. It was like the pounding of an enormous fist on an oak table, or the seal on the bottom of a big parchment degree saying, ‘That’s It!’ The end of Book One. Everything that comes from now on is another volume.” He said that thirteen was “the number of transformation.” Not only were there thirteen spirals, but according to gematria, an occult method of revealing hidden numbers, the number 409 became 4 + 0 + 9 = 13.

Glickman had less definitive comments about the Face and Arecibo Reply glyphs that had appeared last summer. He thought the Face meant: “ ‘We are watching you. We are seeing you.’ The authors of the crop circle phenomenon know us better than we know ourselves.” The fact that the image was executed in halftones, like an image from a newspaper, seemed significant. “Perhaps they are saying that reality only exists where pure light and pure dark merge to form an image.” He had scathing comments about the original Arecibo message sent by SETI: “This is how we represent our selves to the stars? Quantity and chemistry? Size and number? What about Shakespeare? What about Gothic cathedrals?” By giving us exactly what we said we wanted, the Arecibo Response was mocking us.

“Is there anyone out there as stupid as us?” Glickman asked the audience.

AT THE CONFERENCE, I bought a black T-shirt featuring one of the most elegant formations, of circles overlapping to form crescent shapes, abstractly suggesting a winged angel. I stuck the T-shirt in my shoulder bag. When I returned to my room that night, I was disappointed to find the T-shirt was gone—unusual for me, as I tend to be good at holding on to my possessions. I couldn’t remember opening my bag, and I had no idea how the shirt could have fallen out.

The final talk at the conference required a separate fee. The speaker was Dolores Cannon, a hypnotherapist from Arkansas, author of books on Nostradamus and on the extraterrestrial visitors she called “The Custodians.” Her books were international hits, especially popular in East Europe and Russia. A grandmotherly woman in her sixties with white hair and glasses, Cannon sported a lime-green polyester pantsuit.

She asserted that The Custodians were responsible for all the formations. “They have overseen the evolution of humanity since the planet cooled down enough to support life,” she said. Despite the terrifying and repulsive dimensions of most abduction accounts, Cannon insisted that “ET” was a benevolent species who had attained a high level of spiritual and technological perfection. “ET doesn’t need to eat or sleep the way you and I do. They are so much closer to The Light,” Cannon said. “On their ships, they have special rooms where they go to bathe in The Light. That’s all they need, that’s how spiritually advanced they are.”

The Custodians were responsible for the abductions, but these events had been misconstrued by many people. According to Cannon, ET was only interested in our welfare. “Recently things haven’t been going too well for the human race and ET is here to help reset our evolutionary destiny by making genetic changes to ensure the human race continues.” They were deeply concerned that we might cause an unintentional environmental catastrophe. According to Cannon, if there was a catastrophe, they would take us away to another world that they were preparing for our continued evolution.

Cannon spoke in a lulling monotone. Her flat vocal style seemed a product of her hypnotherapy training, and it had a numbing effect on her listeners—at least it did on me. The town hall was packed for her lecture, drawing a different crowd than the conference, including many older people and local hippies. The area around Glastonbury is a center for UFO encounters—in the pubs, I had spoken with locals who all described seeing strange craft or “balls of light.” It made sense that they would come out for her talk—they were struggling for answers. The audience seemed rapt in attention as Cannon recounted stories from her regression therapy. She said that sometimes her sessions would be interrupted by ET, who would communicate with her directly, speaking through the bodies of her hypnotized patients.

Generally, I am not particularly sensitive to the types of “subtle energies” that psychics and “light workers” pick up—they tend to be too subtle for me. However, as Cannon spoke, I became increasingly aware of something unusual in the room, like vortices swirling above the heads of the audience. It seemed I could sense the entities she was discussing, hovering in the air above us. My intuition was that those entities were probing and testing the lulled awareness of the listeners, looking for entry points, seeking to fasten on to their psyche, like mind-parasites.

A strange thought occurred to me: Dolores Cannon, as benign and matronly as she seemed in her lime-green ensemble, was allied, consciously or not, with the visitors. As I listened to her, I felt I had entered the frame of a David Cronenberg movie, staring at the weird and improbable banality of polyester-pantsuited malevolence. I shivered—as I had, months after my DPT trip, when I happened to encounter a quote from St. Paul: “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

In Tibetan Buddhism, magical practices involve creating “tulpas,” known in Western occultism as thought-forms. Tulpas, thought-forms, are imaginal entities that can be given energy and artificial life through rituals, meditations, and other workings. The poet W. B. Yeats started a magical order in which he tried to revive certain Celtic deities through visualization and ceremonies. One of these, the “white jester,” apparently gained enough independent vitality to become visible to a few of Yeats’s friends, who were not aware of what he was doing. John Michell, chronicler of Glastonbury legends, considered old fables in which the stone circles, built around 3000 BC, were constructed by giants summoned up by tribal warlocks. “Those who are knowledgeable in the arts of raising spirits and creating thought-forms have written that it is often easier to produce phantoms than to dissolve them. In the course of time they become more solid and may even bleed when wounded. The magicians of the age of Taurus were adept in forming giants and monsters, but like all technologies theirs had unwanted side effects. Not all the spirits they raised were properly laid to rest, and some lingered about the countryside to establish a breed of monsters.” It occurred to me that hypnotic regression might be the return of this unsavory magical practice—the ensouling of thought-forms—hidden under a cloak of psychology. With or without conscious intent, the psychologist acts as sorcerer, turning psychic energies into entities, through his attention and articulation.

After one hypnotherapy session, Whitley Strieber found a “vivid image” of one of the visitors emerging in his mind, as perfectly rendered as a photograph, staying there for several days. He was able to make the entity move in any way he pleased, taking the opportunity to describe it in great detail in his book, even having a friend paint what he saw. “We don’t know a thing about conjuring and magic,” Strieber wrote. “We’ve dismissed it all, we who love science too much. It could be that very real physical entities can emerge out of the unconscious.” Through her work, Cannon—like the unwilling, unwitting Strieber—was helping the visitors to gain solidity, bringing them nearer to our realm. Like a villain from the Harry Potter series, she was a sorcerer allied with underworld forces—at any rate, that was my exciting and unnerving conclusion.

When it was time for questions, I decided to test these murky waters. “It is quite a story you tell,” I said. “But how can you be so certain that these entities are benevolent? How do you know they aren’t just using you to promote their own agenda? And who do you think are the ‘unclean spirits like frogs’ described in the book of Revelation?”

“Oh, no,” Cannon replied in her affectless monotone. “ET is here to help us and to look after us. They would never do anything to harm us. Where would you get that idea?”

FRIENDS OF MINE from New York came to visit me at the end of the conference. Angelica and Lee Ann, traveling with Angelica’s two kids, had rented a car to visit me and see some crop circles. Lee Ann was married to Angelica’s younger brother, Tony, one of my closest friends, and pregnant with their first child. We drove to the Silent Circle Cafe, on the road to Avebury, a gathering point for international tourists and UFO enthusiasts pursuing the phenomenon. The cafe featured topological surveys of the region on the wall, dotted with pins indicating the precise locations of recent formations, and photographs of the season’s circles. At the cafe, we learned about the latest formation, which had just been found that morning. We took down the directions and drove out to it.

Crop circles can be hard to find. Often they are set way back on farmers’ lands, on gently sloping hills making visibility difficult. From a distance, along a level surface, a crop formation appears as little more than a slight shading in the color of the field. We walked a long way, and finally found a formation of large rings that was a blatant human creation. The grain had simply been smooshed down by a stick. If this was all we were going to find, it was truly disappointing.

As we walked back toward the car along one of the tractor lines, we cut through the wheat and tried another path. Up ahead, atop a rise, we noticed irregular patches in the rows of crop that seemed to indicate some thing different. We entered a brand-new pattern with its now-familiar palpable energetic charge—a sense of a hovering presence over the scene, inducing hyperreality. As Kirtana, Angelica’s thirteen-year-old daughter, entered the perimeter of this formation, she burst into tears—a common reaction in new crop circles. From the ground, the pattern was difficult to read. We thought it might be a flower, with various rings radiating out from a center. We spent some time sitting in the formation, which had a traditional “nest” of swirled-together wheat at its center.

A few days later, a photo of the pattern was posted on the Internet. The image showed three rectangular frames, their edges suggesting braided rope, each enclosing the next. Appearing on Monday, July 22, 2002, this crop circle was “the first in the history of the phenomenon to utilize an unambiguous rope or cord motif,” wrote Allan Brown.

It is interesting to note that knots are an artifact of our 3 dimensional material reality, as topologically a knot will unravel itself when rendered in any higher dimensional space. . . . I am reminded of an umbilical cord whenever I look at this formation.

Perhaps the formation is indicating a birthing into higher dimensional space, in which the paradoxical polarities of duality are unraveled and made whole again.

The image showed a union of circle and square—traditional representations, in sacred geometry, of Heaven and Earth. Karen Douglas, a researcher and organizer of the Glastonbury conference, theorized that “the rope motif signified the binding connection between these two realms.”

We returned to the car and Lee Ann opened the passenger door. The black T-shirt I had bought and lost several days ago, seventy miles away, was lying there, draped across the backseat, witnessed by Lee Ann and Angelica. The T-shirt had disappeared before they arrived in Glastonbury. There seemed no conceivable way I could have been responsible for the shirt ending up in the car, unless I had forgotten a whole series of actions. I recalled my night-long “fairy-world” visions after my first ascent of the Tor. Living in a realm adjacent to our own, hopscotching through our world like quantum tricksters, fairies in fairy tales are often mischievous beings, playing with humans by stealing objects or moving things around, sometimes returning what they borrowed. Were they teasing me? Was my mind playing tricks on me, or were the old fables more than fictive? Were the flickering fairies another archetype, like the gobliny Grays, elusively reasserting their archaic privileges in our postmodern present tense?

Share this post