Eclipses, Stonehenge, and World Ages

Plus an eclipse offering for our upcoming regenerative leadership summit

Traditionally, eclipses were seen as incredibly powerful, spiritually significant events. Stonehenge was built over 5,000 years ago in order to accurately predict eclipses: An extraordinary example of archaic engineering that still functions today. For the ancients, eclipses might indicate a profound shift in the Ages or a movement into a new structure of human consciousness, or provide an opportunity to commune with the gods. I wrote at length about Stonehenge, which both predicted eclipses and harmonized the solar and lunar cycles in one monumental construction, in my book Quetzalcoatl Returns. I have included that section, below, for those who want to dive deeper into ancient archaeology and planetary harmonics!

We are three weeks away from launching our next seminar, Embracing Our Emergency. This seminar brings together an extraordinary lineup of movement builders and thought leaders, all of them notable for their courage and commitment to justice. People like Bill McKibben, Jane Fonda, Doug Good Feather, Nate Hagens — to name a few — are among a rare breed of heroic human who speak truth to power and put themselves on the line to try to change our destructive, unsustainable society before we hit the wall. We can learn so much from them. In celebration of the eclipse, we are offering half-priced tickets to our seminar, available today and tomorrow.

In a sense, we live in a society that is under a long eclipse — a civilization based on lies and delusion, disregarding our innate relationship to the natural world. This culture has put future generations in peril in its insatiable quest for profit and endless unsustainable growth. We all know in our hearts that this system can't and won’t continue for too much longer. But we don't know what comes after it. Most people are totally unprepared for what is going to happen as what Hagens calls the "Great Simplification" continues.

Since our institutions will not help us, we must take it upon ourselves to learn and prepare for what’s coming.

With Embracing Our Emergency, we offer you the opportunity to join a new cadre of regenerative leaders. Over the five weeks, you will gain a deep understanding of the current state of the global climate movement as you access the tools and context you need to make productive, positive changes in your own life and community. During our seminar, you will have an opportunity to develop an action plan for the future that helps you flourish and thrive even as life becomes difficult — even with surprise disruptions or shortages.

Sign up today for 1/2 off the full price.

We will also explore more holistic ideas and theories: For instance, the idea that the current planetary "polycrisis" is our invitation for personal growth and planetary initiation: Instead of ignoring the polycrisis as long as possible, we can take it our our calling to access our inner greatness. Neil Theise, author of the bestselling Notes on Complexity, will help us reframe the current crisis as part of a long evolutionary cycle, where destruction leads to rebirth and recreation. Visionary engineers like James Ehrlich of RegenVillages point toward a self-sufficient future where our buildings produce much of our basic energy and nutrient needs.

We will be meeting on Sundays and Wednesdays — but don’t worry if you can’t make the live sessions. All of the meetings will be recorded so you can access them at your leisure. We will also have a social network and a resource library for those who want to go deeper.

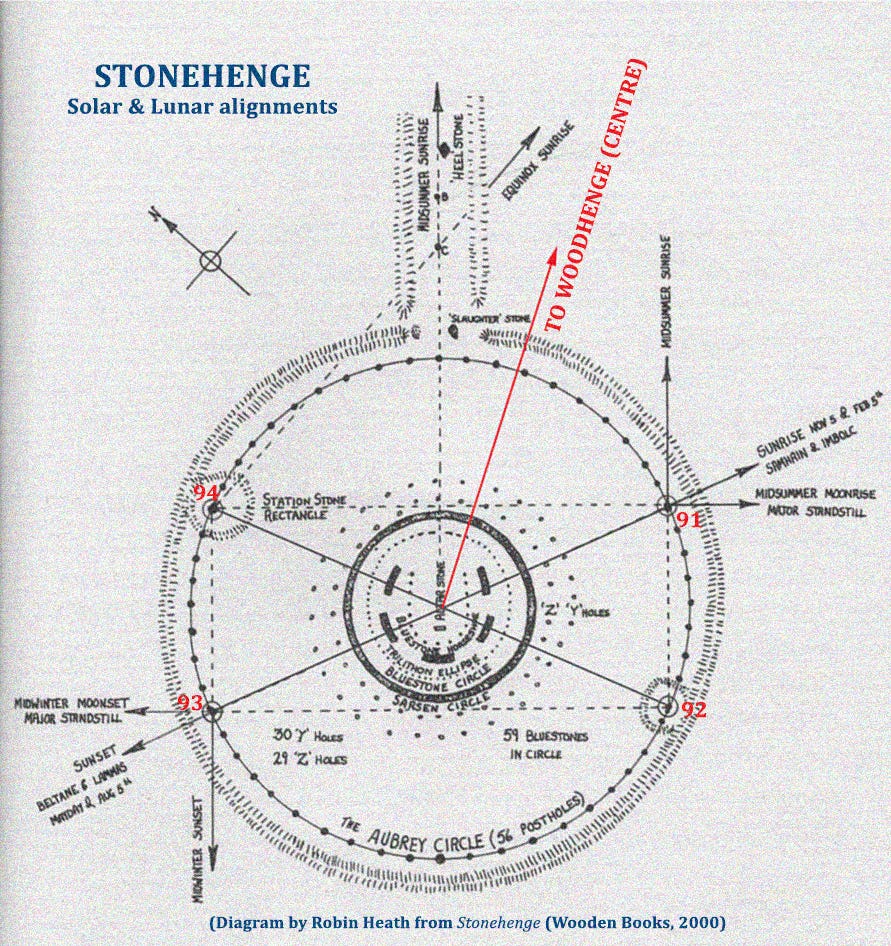

According to astronomer Gerald Hawkins, author of Stonehenge Decoded—a 1963 bestseller that sparked the entire discipline of archaeoastronomy— Stonehenge was an astronomical “computer,” printing out, ad infinitum, a coded message of solar-lunar integration. The temple is on a raised platform, encircled by fifty-six evenly spaced holes, known as the “Aubrey circle,” that probably held wooden posts. By moving stones along these posts each day, Stonehenge functioned as an accurate predictor of lunar eclipses. Its numerous alignments and sight lines followed, and synchronized, the movements of Sun and Moon over long cycles, lasting decades, requiring occasional reprogramming.

Many of the now-ragged bluestone blocks used to build Stonehenge came from the Preseli Mountains of West Wales, 135 miles away—the means used to transport them remain a matter of controversy. Within the outer circle, there stand remnants of five post-and-lintel constructs of a much greater size and heft—the upright stones weighing as much as fifty tons— in a horseshoe shape. These massive blocks were brought from twenty-four miles away at Flyfield Down, near Avebury. When the initial megalithic structures were built, between 3000 and 2600 BC, the climate of England was similar to today’s northern Spain, and the material culture of its inhabitants was equivalent to that of Native Americans before colonialism. Historians and archaeologists have biased us to think of prehistoric or premodern cultures as societies of scarcity; this was certainly not the case in ancient Britain, as they had the time, as well as determination, to plan and build these enormous outdoor temples, constructing from five to ten thousand stone circles over a thousand-year period.

“The collection of stones, mounds, and ditches we collectively call Stonehenge evolved over a period of at least 1,500 years, an unmatched period of evolution for any cultural artifact,” writes Robin Heath in Sun, Moon & Stonehenge: Proof of High Culture in Ancient Britain. The construction was continually modified as long as it remained in use. Although the monument is popularly identified with the Druids, its development, as well as decline, predated the druidic culture of Britain, which flourished during the period of the Roman Empire, by millennia. The practice of building stone circles continued for as long as two thousand years, before it ended “remarkably suddenly,” notes Heath, a former civil engineer and head of the technology department at a Welsh college, and “the purpose and the meaning of the stones, and the culture which deemed them so important, apparently became lost to us.”

Following Hawkins’s work on Stonehenge by more than a generation, Heath’s book is a remarkable achievement, recovering from the crude stones an extraordinary legacy—a prehistoric “high culture”—accomplishing for Stonehenge what “alternative archaeologists” such as Schwaller de Lubicz and Robert Bauval discovered through studies of the pyramids of Egypt. In Heath’s analysis, Stonehenge is shown to encode an entire canon of sacred knowledge, including a precise astronomical understanding of the placement, shape, and movement of the Earth and its relationship to Sun and Moon, as well as pragmatic use of the “golden ratio,” phi, which appears in many forms in organic life, encoded in the proportions of the human body itself. The Neolithic culture of prehistoric Britain was evidently obsessed with making accurate observations of the world around it, and systemizing its understanding for the benefit of future generations. “Perhaps the best one can do is to recognize that Stonehenge was built by people identical to ourselves, albeit very different in culture, yet perhaps superior in their ability to think about some fundamental issues concerning human life on Earth,” he writes.

Heath’s work builds upon the work of John Michell, who showed, in his A New View Over Atlantis, that Stonehenge included complex sevenfold geometry in its layout, and a near-perfect representation of the “squared circle.” The problem of squaring the circle—in which the perimeter of a square equals the circumference of a circle—is an ancient one with important symbolic overtones. The square represents “Earth” and matter while the circle symbolizes “Heaven” and divinity; integrating these forms fascinated the ancient mind. This difficult problem cannot be solved—as a German mathematician proved in the late nineteenth century—through ordinary calculations or geometrical means involving a compass and straightedge. Michell found that the proportions of the squared circle implied by relationships within Stonehenge was identical to one produced, numinously enough, by bringing the Moon down to touch the Earth, then drawing a square that tangents the Earth, and a circle with its circumference defined by the Moon’s centerpoint.

During the 1,500 years of its active life, Stonehenge went through many modifications, apparently switching from a lunar to a solar emphasis. “Stonehenge began as a lunar temple and became Apollo’s temple, reflecting perfectly the changes in the social fabric of the societies which evolved the monument,” Heath writes. In Heath’s account, the placement of the temple reveals careful forethought. Along the fifty-six holes of the Aubrey circle, four boulders were placed to create a “station stone rectangle” that was necessary for charting the solstitial and equinoctial risings that were essential to the builders’ purpose.

“The right-angle arrangement between the Sun’s solstitial and the Moon’s extreme . . . risings is unique to the latitude of Stonehenge,” Heath writes. In other words, if the monument was not placed at its precise spot—“located at a latitude which is one seventh of the circumference of the Earth referred to the equator”—the alignments would not have worked. The “station stone” rectangle would have been a crooked parallelogram.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.