From Capitalism to Technofeudalism

We are undergoing a base/superstructure transition. What does it mean for our future?

We had a fantastic first session of Building Our Regenerative Future last Sunday, with talks from Art Brock (Holochain), James Ehrlich (RegenVillage), and Jamie Wheal (Recapture the Rapture). I am still reflecting on what our presenters shared. You can still join our seminar, catch the first session on recording and participate in the next five weeks (half-priced tickets still available for paid annual subscribers).

Brock’s Holochain is a framework for building decentralized applications, providing an alternative to blockchain technology. I was very excited about Holochain when I first learned about it, five or six years ago. Rather than another blockchain, Holochain takes a different approach. As an entirely peer-to-peer network that people can run off their home devices, Holochain doesn’t allow for single points of failure or top-down control.

As a completely distributed network, Holochain builds user autonomy and decentralization into its architecture. While blockchain employs a global consensus model (proof of stake or proof of work), Holochain uses what is called an agent-centric approach. Each participant or agent in the network maintains their own chain, called a 'source chain’. In theory, this makes Holochain highly scalable, since transactions can be processed in parallel. However, they haven’t found, as of yet, a “killer app” compelling large-scale adoption, so the whole enterprise seems to linger, like so many noble endeavors, in a kind of intangible space of potentiality.

For our seminar, Brock presented some fascinating ideas about currencies. He believes we already make use of many different forms of currency beyond purely financial currency (i.e., money). There are reputational currencies, grades and degrees, certificates for organic food, and so on. He sees currency as not just money but as a range of formal systems or tools that shape, enable, and measure various flows and interactions. Currencies can be designed to mediate between social, ecological, or cultural capital.

To build more resilient and regenerative capacity, Brock envisions the creation of diverse currencies tailored to specific community needs and contexts. This diversity would allow for a more nuanced approach to value exchange and resource allocation. Local, regenerative currencies can be designed to support enhanced cooperation, community engagement, and mutual aid. These would contrast with our current one-dimensional monetary form of exchange, which promotes competition and hyper-individualism.

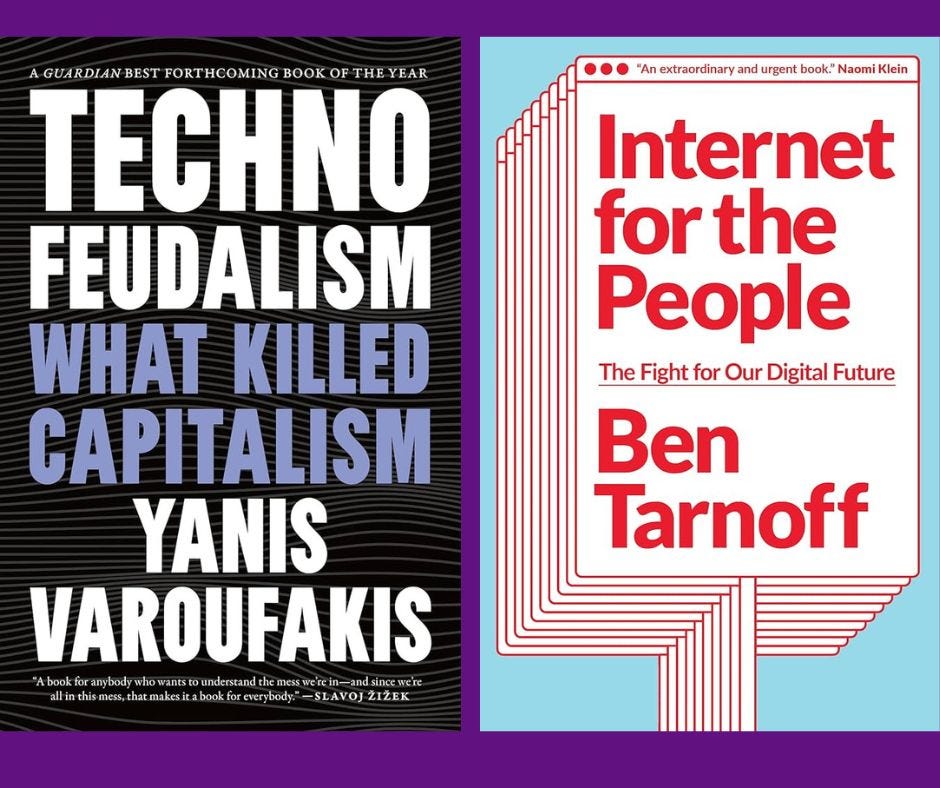

Brock’s ideas synergize well with two fantastic books I am reading now: Technofeudalism by Yannis Varfoukanis, formerly Finance Minister of Greece, and Internet for the People by Ben Tarnoff. Both books explore how the transformation of the Internet into a private, commercial enterprise has unleashed disastrous social consequences. As Tarnoff notes, the Internet was originally built by government scientists as a public works project, from taxpayer money, and later handed over to corporate interests with no strings attached:

In the 1990s, the US government gave the private sector a network created at enormous public expense. Corporations took over the internet’s physical infrastructure and made money from selling access to it. But privatization didn’t stop there. The real money didn’t lie in monetizing access, but in monetizing activity—that is, in what people did once they got online. So privatization ascended to the upper floors, to the layer where the internet is experienced. Here, in the 2000s and 2010s, the so-called platforms arose: Google, Amazon, Uber, and the rest. These empires finished what the 1990s had started. They pushed privatization up the stack. The profit motive came to organize not only the low-level plumbing of the network but every aspect of online life.

I find it extraordinary that “we, the people” accepted the privatization commercialization of the Internet, for the most part, with little pushback. This can only be a result of the mass indoctrination into the cult of Neoliberalism, which rejects any deep expression of a public good or a commons-based approach as “bad,” akin to socialism.

Varfoukanis argues that the development of the privatized Internet—the integration of digital technology into finance, media, and every aspect of our lives—has actually brought about the end of Capitalism in its traditional form. He believes we have now entered a different economic order. He calls this “technofeudalism,” dominated by “cloud capital,” where personal identity has been outsourced to private companies, who monetize our attention.

Varfoukanis compares this to the Enclosure movement of the 18th and 19th Century, when land traditionally held in common was privatized and taken over by the wealthy: “As with the original Enclosures, some form of fence would be necessary to keep the masses out of such an important resource. In the eighteenth century, it was land that the many were denied access to. In the twenty-first century, it is access to our own identity.”

I first grasped the centrality of this problem of identity to the future of the Internet over fifteen years ago. Addressing the identity problem was one of the primary goals of the company I started back then, Evolver: We wanted to integrate a non-commodified identity layer into our social network (back then, we naively thought we could build a competing product to Facebook, but capital was not on our side). This would give users control over what aspects of their own identity and personal data they shared or revealed in any online interactions with different organizations and businesses.

In fact, it remains a great idea to construct an identity layer for the Internet that is not privately owned or corrupted by profiteering. We should have control over our own data, and have the capacity to share or monetize it as we choose. Holochain might provide an end-run around this problem by “disintermediating” people from the centralized Internet—if it works as advertised, which I can’t say, and if it could scale.

Here is a current thought I want to share and will elaborate in future essays: With the rise of AI/robotics/cloud capital, we are undergoing a base/superstructure transition that is as deep as what happened in the 1950s and ‘60s. Back then, post-war affluence led to a liberalization of society as the Anglo-European “Empire” transitioned from direct colonialism to indirect (debt-based) neo-colonialism. This shift led to the radical movements of the 60s — and eventually the “financialization” of the US economy, the decoupling of the dollar from gold, the off-shoring of productive work and the use of the US trade deficit to blow up Wall Street profits at the expense of the real economy.

The radical movements of the 1960s (Black Panthers, Green movement, Feminist movement, etcetera) had the legitimate potential to challenge and change the system. Hence, they were effectively suppressed (the assassinations of the Kennedys, Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, the Kent State shootings; the flooding of the inner cities with crack, and so on). Up until today, as we saw with the orchestrated attack on the Bernie Sanders’ campaign, the system thwarts any authentic (Leftist) alternative.

During a base/superstructure transition, new opportunities for radical alternatives can and will emerge. The rapid advancement in AI and robotics is already reshaping the economy and re-weaving our social fabric. These technologies will rapidly alter labor markets, production processes, and the nature of work itself, causing significant displacements in the workforce. The ongoing mass lay-off/"downsizing" of cognitive workers via AI creates the possibility for a new awareness and self-identification to take root among the global class of cognitive workers (what Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri defined as "multitude"), who could (but, I must admit, probably won’t) come to recognize themselves as a new revolutionary class.

As Naomi Klein explores in Doppelganger, the neo-Fascistic and Libertarian Right exploit the current, deepening turbulence by spreading distorted analyses that blame individuals and conspiratorial networks, instead of offering a coherent structural and systemic analysis. This ends up dividing and fragmenting the people, serving the short-term interests of an elite group of wealth holders, to our collective detriment. Fascism is an increasingly likely alternative at this point — particularly as frightened people react instinctively to crises in food production, employment, and mass migrations. Any other, systemic alternative rooted in a deeper transformation has not been well-articulated (I tried with How Soon Is Now) and lacks capital behind it.

A new social movement would need to offer a clear analysis, along with a focused strategy and defined set of goals. This needs to include an authentic response to the biospheric emergency, which hangs over all of our heads. Such a movement, to be effective, must target the younger generation who are a bit lost in the current miasma, detached from political and social realities, addicted to virtual worlds and mood-stabilizers, entrained to ignore the increasingly pervasive phenomenological reality which increasingly impinges on all of our lives.

Systemic change seems unlikely. However, as conditions change, new possibilities emerge. So we might as well try.

“Selling us back our own identities” has been going on since the advent of marketing. They’re just getting better at it.

Or, one could argue that this sort of soul separation has been at the core of most modern religions, which in turn support the ruling class du jour. I think this was described best by Alan Watts in his wonderful The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are.

https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680231226387

Restoring sanity via metacognitive worldview reflect on precolonial worldview is the necessary transformative goal...