How Burning Man Failed

Transformational festivals, the psychedelic renaissance, and cryptocurrencies: Thoughts of an apostate

Burning Man is happening this week. I am not there and haven’t gone since 2018. As followers of my work know, I was deeply connected to the festival for a long time. I wrote about it in my first books. I also wrote features about it for Rolling Stone and ArtForum. I still hope to return, maybe next year, primarily to reconnect with many old friends from the West Coast, albeit guiltily. I suspect it won’t go on too much longer in its current form, due to the rising heat that is melting the planet. But of course, I could be wrong.

(Some friends of mine organized a climate protest this year on the road into Burning Man, demanding an end to private jets and single-use plastic at the event. They were quickly shut down and shrugged off, but at least made it into The Guardian).

As some readers may recall, I love Burning Man and consider it a massive disappointment. When I first visited back in 2000, I was overcome with enthusiasm, inspiration — many people still feel this, today, when they go for the first time. I still recall that wonderfully intoxicating sense of arriving at a “free” or liberated cultural zone where, in theory, you can recreate yourself in any way you want, express yourself in any way, as long as it doesn’t cause harm to anyone else.

My life revolved around New York City art, literary, and media circles before that point. These scenes operated according to fairly tight rules. Although alcohol-saturated, they were very conservative in some ways. Burning Man was a mind-blowing revelation. As I wrote in Breaking Open the Head (2002):

At moments, Burning Man reminded me of Norman Mailer's Armies of the Night, an ambivalent take on the counterculture during the 1967 Pentagon march. "The dress ball was going into battle," he wrote. "Now the witches were here, and rites of exorcism, and black terrors of the night .. .the hippies had gone from Tibet to Christ to the Middle Ages, now they were Revolutionary Alchemists." Like most literati, the hard-drinking Mailer hated psychedelics: "The nightmare was in the echo of those trips which had fractured their sense of past and present. . . . The history of the past was being exploded right into the present: perhaps there were now lacunae in the firmament of the past, holes where once had been the psychic reality of an era which was gone."

Since Mailer's book, memory loss — mass-cultural amnesia, rampant Alzheimer's, disconnection from history — has become our dominant cultural paradigm. Burning Man, on the other hand, celebrates "the history of the past as it is exploded into the present — as kitsch spectacle, mythic image, or, in [Walter] Benjamin's phrase, "profane illumination." It is possible to witness a fully costumed Aztec sacrifice atop a cardboard ziggurat, undergo a mock Egyptian burial using rites from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, participate in a Shiva-ite fire ritual — all in an hour. The entire event spoofs some 1970s retro sci-fi fantasy of post-apocalyptic tribalism, and the big man's climactic burning summons up ancient druidic sacrificial rites from the collective memory banks. The constant riffing on the past amplifies the festival's hallucinatory ambience. Like the effect of certain chemicals, Burning Man changes one's sense of time, revealing the mythic underpinnings, the whispers of eternity, underneath the most ordinary moment. Perhaps this is what Danger Ranger meant when he told me, "I found out there is a way your consciousness can go beyond what we call Now, and I rode the shockwave of inverse time.”

Burning Man seemed to reveal how society, as a whole, could (and, I believed, eventually would) be reconstructed around the psychedelic anarchist vision. The festival showed me it was possible to deprogram people, en masse, from the economic shackles, blind ambitions, and incessant status-seeking of normative culture. In my naive excitement, I saw Burning Man as a porto-revolutionary model for the future— in How Soon Is Now, I joked that the festival was my version of the Paris Communes (1848), a short-lived worker-run experiment eventually crushed by Napoleon III, which inspired Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

Over time it became clear — particularly after the death of Larry Harvey, its founder — that the dominant ethos underlying Burning Man was a kind of occult-tinged free market Libertarianism, influenced by transhumanism and the technological Singularity. Back in the early 2000s, Burning Man mocked itself vigorously. It had a hard, Terence McKenna / Robert Anton Wilson edge. We felt we were exploring Chapel Perilous, awaiting the Eschaton.

As Burning Man expanded and became more popular, it lost its self-parodying humor, its self-critical irony, and its encompassing social vision, to a great extent. It started to feel increasingly hollow, shallow, and narcissistic. Much of the art now seems designed to provide a fitting backdrop for Instagram selfies. The outfits and hats became copycats of each other. Burners no longer explore much originality of self-expression. They follow the pre-set script, the round-the-clock EDM schedule

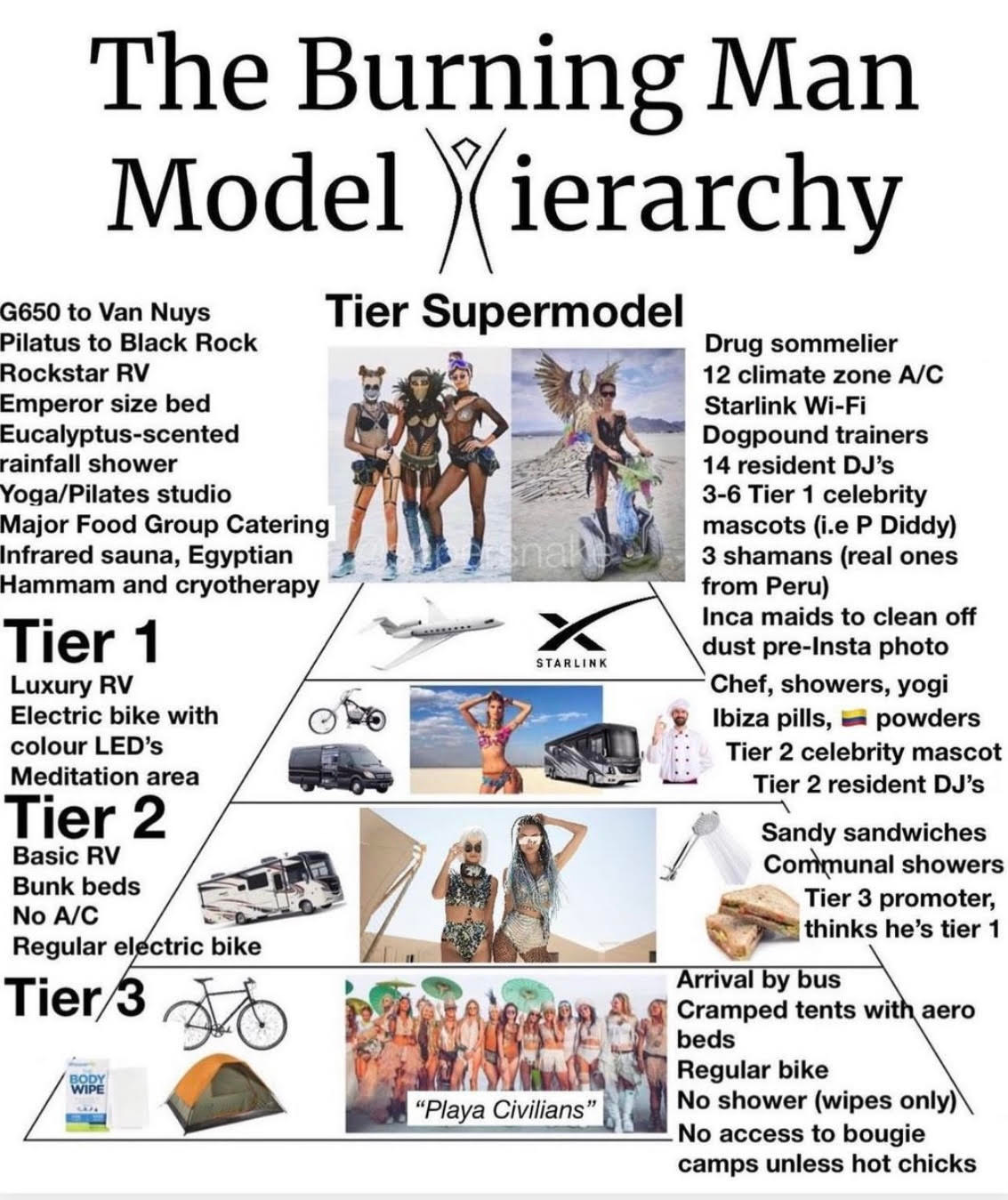

Anthropologically, I found it interesting — instructive — to see Burning Man crystallize into a somewhat stuck, increasingly banal and homogenous culture over nearly two decades. As more and more people of status and wealth swarmed the event, it replicated the status hierarchies found in the “default world,” although with a psychedelic/floaty Ketamine tinge.

There was always an innate beauty hierarchy at Burning Man; over time, wealth started to play a greater role in determining the festival’s focus. Wealthy Burners raised millions of dollars for their art cars, sculptures, and mega-domes. As Keith Spencer wrote in Jacobin, the rich Burners, by choosing and bankrolling the major art projects, impose their visions on everyone else — just like in the real world. Art cars are, for a nomadic jet-set made up of tech tycoons and trustafarians, similar to the yachts that circle Ibiza or Monaco: Emblems of status and privilege.

Back in the old days, I was considered a bit of a problem for the Burning Man org because I made the obvious connection between the festival and the still-taboo subject of psychedelics in my books. For many years, Burning Man didn’t allow the Multidisciplinary Approach to Psychedelic Substances (MAPS) to promote its Zendos (safe spaces for bad trips) publicly. The organizers worried this would be tantamount to admitting knowledge of drug use at the event. In the context of that time, this made sense. The 2002 RAVE (Reducing Americans Vulnerability to Ecstasy) Act stipulated that any organizer who put on a festival and knew there were drugs being sold there was as liable as the dealers

.We seem to have jumped that particular hurdle, however. Now psychedelic use is out in the open at the Burn. In fact, Burning Man is the epicenter of the new psychedelic renaissance, its culture and industry. It is where the people seeking to capitalize on and promote psychedelics gather every year to celebrate themselves and their achievements. In itself, Burning Man has morphed into its own entertainment-industrial complex, franchising itself around the world with regional festivals that adopt the ten principles (which are, indeed, brilliant).

The main problem with Burning Man — and with the current psychedelic renaissance — is the lack of a meaningful systems-level critique. Such a critique would understand humanity’s natural vitalizing impulses — our innate yearning for ecstasy and transcendence through altered states, eroticism, liberated movement, and community communion — as antidotes to the planet-killing monstrosity that is post-industrial Capitalism, reductive materialism, and alienated consumerism. Beyond making the critique, we would turn it into collective action.

Most Burners get trapped by their personal experience of liberating ecstasy, even as it becomes repetitive and turns into its own form of hyper-addictive consumerism (consuming spectacles and exotic experiences is still consumerism). Year after year, festival after festival, people seek the same hedonistic rewards. The culture supports them in this compulsion. Most never take the next step, which requires turning their personal realization of the potential for liberation into a political, activist ethos — to recognize, as Walter Benjamin put it, “For those without hope, hope was given to us.”

There’s much more I could say about all of this. Another interesting phenomenon I observed was the link between Burning Man and the cryptocurrency explosion. I remember, back around 2010 or so, there was a growing sense of anxiety over the planetary emergency — the “polycrisis” — among, at least, the Burner elites.