It was twenty years ago today...

Terrorism, Prophecy, and the Noosphere

Dear People,

Fifteen years ago I published 2012: The Return Of Quetzalcoatl on ancient and indigenous prophecies, the nature of time, the physics of consciousness, Apocalypse, and other such trifling matters. Today the book feels more relevant then ever. I’m currently producing a full audiobook version, narrated by my dear friend Paradox Pollack and produced by Jordan Albert, to be released this fall. In the meantime, I’m offering the audio version of Chapter Five as an introductory free sample. This section details my personal experiences of 9/11. I hope you find it inspiring! Here is the link for the audio. The audio book will be made free for Subscribers and otherwise available through usual channels in a month or two. Below is the text of the chapter, if you prefer reading it.

2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl

Chapter Five

What appears to be the established order of present-day civilization is actually only the inert but spectacular momentum of a high velocity vehicle whose engine has already stopped functioning. - JOSÉ ARGÜELLES, Earth Ascending

In the spring of 2001, I agreed to publish a book-length poem by a friend of mine through our small press. The author of the book, Michael Brownstein, was a poet and novelist who had been involved in the post-Beat counterculture of the 1970s, living in Boulder and teaching literature at the Naropa Institute, founded by the Tibetan lama Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, with Allen Ginsberg. Michael also explored psychedelic shamanism—he had introduced me to ayahuasca, and his poem included a long section describing an ayahuasca ceremony he attended in the Amazon, where the oil wells could be heard pounding in the distance. His manuscript was too radically downbeat to be considered by any mainstream publishing house—even I had a lot of trouble, at first, digesting its contents. More than a poem, it was an impassioned outcry against the current order, looking toward an imminent future of abandoned cities and dead lands. He attacked Pasteur’s germ theory of disease, decried the media’s systemic suppression of information—such as reports on the dangers from electromagnetic radiation emitted by cell phones— and incorporated ideas and quotes from left-wing critics such as Vandana Shiva, Jerry Mander, and Noam Chomsky. With the fist-thumping tempo of an old-fashioned fire-and-brimstone sermon, he decried corporate globalization and the oil companies and the poisoning of the biosphere, assailing

This age of manufactured mind.

This push to transform life into products.

This culture drowning the present in the name of the future.This heart of darkness beating its fluid into every cell.

Michael envisioned the year 2012—focus of Mayan cosmology, and an increasingly popular meme in the counterculture—as the time when global cataclysm would consume our depleted, defeated world:

Centuries ago ancient Mayans predicted world upheaval for the year 2012.

The end of their sacred calendar’s five-thousand-year Great Cycle.

Has 2012 come and gone?

The future everyone secretly fears, is it already here?And the past—did it ever really happen?

One fall morning, I finally stopped procrastinating and started to edit Michael’s poetic manifesto, opening his manuscript and spreading the pages across the dining room table. My partner was in our bedroom, breastfeeding our daughter, who was not yet a month old. Outside, we heard the roar of a low-flying airplane and then a loud metallic crunch. We opened the blinds of the loft and saw a flaming crater in one of the World Trade towers, as “9-11” dialed up our current state of planetary emergency. A few moments later, the second tower was hit.

Michael’s book was already titled World on Fire.

GROWING UP IN SOHO during the early 1970s, I recall the construction of the World Trade towers. Even from my child’s vantage point, the arrival of those sleek gray megaliths seemed to suggest a new order of things. Imposing themselves on the skyline of lower Manhattan, they offered an indelible image of the postmodernist technological future our society was supposed to be racing toward, where functionality replaced funk, where the handmade ambience of old-fashioned craft was abandoned for the sterilized swank of the airport lobby. The Twin Towers also represented a shift in economic paradigm. Like a tuning fork, they beamed out the shrill frequency of the rapacious corporate globalization that went into overdrive during the next decades—the accelerating movement away from a production-based economy to the ruthless transactional logic ruled by the speculations of the financial sector, where “futures” are traded by high-speed computer, and the economies of entire Third World nations can be gutted in a few hours. Their fall seemed, also, a movement into a new order of things—or perhaps a new disorder.

It was Jean Baudrillard, the Henny Youngman of contemporary French thought, who quipped that the World Trade towers were not actually destroyed, but committed suicide: “It is almost they who did it, but we who wanted it.” So much has been declaimed about this event that it seems superfluous to offer more words. However, my own impression of 9-11 was of an almost overwhelming déjà vu, an inexplicable feeling of returning or recalling something I had only temporarily forgotten. “The tactics of terrorism are to provoke an excess of reality and to make the system collapse under the weight of this excess,” Baudrillard wrote. And indeed, the attack did seem like an assertion of stark reality, a stern decree from the pointing finger of fate. Refracted through the prism of so many disaster movies and mediated spectacles, 9-11 was deeply shocking, but not surprising. Such a radical negation of the prevailing system of dominance seemed somehow built into the structure itself—a necessary corrective to its global hegemony, for which the Islamic ideology of the terrorists provided only a convenient excuse.

As the towers flamed, I left my house and walked downtown toward them, past dazed survivors covered in gray ash and police squadrons, past blow-dried TV anchors set up on street corners, through crowds rushing away or collected around radios and television screens, as if the media could tell them something more essential than what they could see with their own eyes. I wanted to feel the magnitude of the disaster, to absorb into my skin its biblical proportions, as well as its stage-prop-like unreality. The fall of the towers seemed to confirm William Irwin Thompson’s perception:

Some god or Weltgeist has been making a movie out of us for the past six thousand years, and now we have turned a corner on the movie set of reality and have discovered the boards propping up the two-dimensional monuments of human history. The movement of humanism has reached its limit, and now at that limit it is breaking apart into the opposites of mechanism and mysticism and moving along the circumference of a vast new sphere of posthuman thought.

Watching the chaos, I couldn’t shake the uncanny feeling that I knew about this already—that I had been, in some obscure corner of my soul, even waiting for it to occur.

September 11 was the first event to be witnessed, in real time, by billions of people across the planet. On the level of the collective psyche, this episode had, astonishingly, measurable effects. The Global Consciousness Project at Princeton University conducts one of the most well-organized and ongoing experiments to measure psi as a worldwide phenomenon. In an attempt to take a kind of psychic EEG reading of the planet, Princeton researchers put fifty random number generators in cities around the world, monitoring their constant fluctuations. It has been substantiated repeatedly in psychic experiments that the activity of human consciousness influences random number generators, such as the roulette wheels and slot machines used at casinos. The Princeton experiment reveals a similar effect taking place on a global scale.

The Princeton project documents strong deviations from normal patterns of randomness during major world events and disasters. The most extreme deviation was registered on the morning of September 11, 2001. Even more interesting is the following: Although perturbations in the pattern peaked several hours after the planes hit the World Trade Center, deviations from the norm began a few hours before the catastrophic events. Roger Nelson, the project’s director, notes:

We cannot explain the presence of stark patterns in data that should be random, nor do we have any way of divining their ultimate meaning, yet there appears to be an important message here. When we ask why the disaster in New York and Washington and Pennsylvania should appear to be responsible for a strong signal in our world-wide network of instruments designed to generate random noise, there is no obvious answer. When we look carefully and discover that the [data] might reflect our shock and dismay even before our minds and hearts express it, we confront a still deeper mystery.

Nelson speculates that the Consciousness Project is witnessing the early phases of the self-organization of a global brain. He writes: “It would seem that the new, integrated mind is just beginning to be active, paying attention only to events that inspire strong coherence of attention and feeling. Perhaps the best image is an infant slowly developing awareness, but already capable of strong emotions in response to the comfort of cuddling or to the discomfort of pain.” As of yet, Nelson and his team do not have an analytical framework for interpreting the data they continue to compile.

The Catholic mystic Pierre Teilhard de Chardin foresaw the development of a “new, integrated mind” of global humanity, calling it the “noosphere,” from the Greek word nous, meaning mind. Noting that our planet consists of various layers—a mineral lithosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and atmosphere consisting of troposphere, stratosphere, and ionosphere— Chardin theorized the possible existence of a mental envelope, a layer of thought, encompassing the Earth. The “hominization” of the Earth had concluded the phase of physical evolution, during which species multiplied and developed new powers, leading to an entropic breakdown of the biosphere. This process, Chardin realized, requiring the tapping of the stored energy and amassed mineral resources of the planet, could happen only once. When physical evolution ended, the evolving stem of the Earth switched from the outer layers to the level of cognition, developed through human consciousness, containing the entirety of our thought, as well as the planet’s future evolutionary program. Chardin proposed that the noosphere would eventually develop into “a harmonized collectivity of consciousnesses equivalent to a sort of super-consciousness.”

The activation of the noosphere would be predicated on humanity’s realization of itself and the Earth as constituting a single organism, followed by “the unanimous construction of a spirit of the Earth.” Chardin considered this the logical and even necessary next phase of human evolution into a fully aware and self-reflective species. In his 1938 book, The Phenomenon of Man, he wrote:

The idea is that of the earth not only becoming covered by myriads of grains of thought, but becoming enclosed in a single thinking envelope so as to form, functionally, no more than a single vast grain of thought on the sidereal scale, the plurality of individual reflections grouping themselves together and reinforcing one an other in the act of a single unanimous reflection.

What would it take to activate the noosphere? According to Chardin, “A new domain of psychical expansion—that is what we lack. And it is staring us in the face if we would only raise our heads to look at it.”

FOR SEVERAL WEEKS AFTER THE ATTACKS, the ruins of the Twin Towers continued to smolder—we could watch the effluvial trails from our windows. When the wind changed direction, it blew a metallic-tinged, acrid, gray doom-cloud of powdered fiberglass, concrete, corpses, office products, and other detritus in our direction. Despite the government’s blithe assurances about the quality of the air, we did not want to subject our daughter’s tiny lungs to this clearly poisonous fog. I was also alarmed by the bioterrorism threat. Anthrax had been found in the offices of several Democratic members of Congress and in the mailroom of The New York Times and ABC News, the most liberal outlets of the corporate media. It seemed possible that a widespread attack was on its way. Anything seemed possible, in fact.

To escape this ominous cloud of toxic possibilities, we fled the city several times, renting a car to drive to a friend’s house in Connecticut. It was during one of our emergency getaways that my partner received a call from her mother and learned that her father, a magnate who ran a successful clothing company in Germany, had died the night before. He had been stricken with cancer during the previous winter. His death followed my father’s by almost exactly a year.

The magnate was one of the most impressive men I had known, and certainly the most elegant. Along with my partner’s mother, he had built up his business and then sold it at the peak of its success to focus on his passion, which was collecting contemporary art. The magnate was a man of forceful enthusiasms, a great believer in science, modern progress, and free enterprise. He loved to debate the issues of the day and to manifest his will through his projects, which were usually successful. He was six feet, three inches tall, with a long and handsome face, and a tremendous sartorial flair. His wife was his perfect match; she was beautiful, imposingly glamorous, and a trained art historian. In the mid-1990s, after the wall came down, they relocated to Berlin to participate in the revival of Germany’s capital. They bought and renovated a building complex in the center of Mitte, the old Jewish quarter, installing their art collection on the top floors. Above this complex, they built an extra level, with glass walls, for their own bedrooms, guest apartment, and swimming pool—the transparency seemed to the point, as the magnate and his wife were proud to present themselves to the world as model citizens. On weekends, visitors were invited to tour the collection. In order to do so, they had to take off their shoes and wear the gray felt slippers that protected the wood floors from damage.

At their home in Berlin, they threw fabulous parties, dinners, and brunches in their main room, on long tables festooned with acorns and flowers, underneath bright-painted Frank Stella sculptures that projected jaggedly from the walls. My partner’s parents accepted, and almost expected, eccentric or drunkenly wild behavior from artists, knowing that artists often suffered, embracing personal chaos or indulging in intoxication, to find inspiration. They were gracious hosts, and rarely offended.

I MET MY PARTNER at a party thrown by mutual friends in the art world. In my first memory of her, she stands on the corner of the dance floor, wearing a shiny blue down coat, her head bobbing back and forth, her eyes sparkling with curiosity. She was tall and thin and highly attractive, her brown hair cut in an angular swoop around her long neck. We spoke for a while. I found her accent hard to understand or to place. She was German but had lived in France for ten years before moving to the United States. After we met, we started to run into each other constantly—she lived a half block from the office I was using to write a novel. It seemed like whenever I left my work—whether 4 p.m. or 3:30 a.m.—I would encounter her on the corner. We started to spend time together. I learned that she had only been in New York for a year, moving from Paris to take a job as an editor at an art magazine. She had a wonderful, engaging smile.

We discovered a shared enthusiasm for the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard, the master of the ceaseless complaint. Many of Bernhard’s works take the form of extended rants from isolated narrators, mathematicians or philosophers or failed pianists, unfurling their alienation in long and repetitive sentences. Our attraction to this writer was no accident. My partner and I shared a Bernhardian ambivalence about existence; while this brought us together, it also made our relationship more difficult. Our ambivalences manifested in different ways and in frequent struggles. We flickered between phases of profound complicity and mutual exasperation.

A distinct pleasure of being a bohemian outsider is that you can sometimes subvert social hierarchies. Through my partner, I was ushered into her family’s world of high-tension prestige and high-end culture. Spending long stretches at their house in Berlin, I felt like an accidental barbarian who had not only gotten through the gates but somehow ended up luxuriating in the inner sanctum.

I once saw the magnate by accident, across Prince Street in SoHo. I waved at him but he did not notice me. Wearing an elegant overcoat and a black Comme des Garçons suit, he was striding down the street purpose fully, his carriage erect, with his eyes fixed on the distance, as if locked in on his goal. He was every inch the empire builder. I could not help but compare his confident gait with my own slouchy and digressive style of walking—and being—my eyes ever turning this way and that, observing people, especially women, and pursuing my own reflections wherever they led. There were aspects of him that, in my own way, I tried to emulate— and others I only wished that I could.

Only a few weeks before he died, we had gone to Berlin for the wedding of my partner’s brother, a genetics researcher, who had compressed his engagement so that the magnate could preside over the nuptials. The ceremony gave us the chance to introduce him to his first grandchild. Sitting at his desk overlooking the church towers and rooftops of Mitte, he held her in his arms, and wept.

The wedding was held at the Alte Nationalgalerie, on Berlin’s museum island, in the dark-wood-paneled main hall, just restored and not yet open to the public. During the service, the magnate rose carefully from his wheel chair to read a passage from the Bible, in German and then in English:

“Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not Love, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal,” he read, his voice trembling. “And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not Love, I am nothing. And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not Love, it profiteth me nothing.”

Although he read so movingly, he considered the text to be nothing more than great literature, expressing humanity’s irrational and absurd yearning for transcendence. Like many men of his generation—like my father as well—he believed that science had disproved God, as well as mysticism, once and for all. When the magnate was healthy, I had been unable to impress him with my radical views on corporate globalization and shamanism. In the months before he died, I also failed in my fumbling attempts to open his awareness to the possibility of other realms of being, of bardo states and spirit guides.

One morning, a few years after the event, I suddenly recalled that wedding, and wanted to review the passage he had read that day. Being a biblical illiterate, I didn’t know where to find it. When I checked my computer a few hours later, I found that a friend of mine had just sent me the entire text via e-mail—as if by noospheric delivery service. The passage was from St. Paul’s Letter to the Corinthians. My friend, the daughter of a Protestant theologian, later told me she awoke in the middle of the night and felt compelled to do this—as if an invisible hand were pressing the back of her head. She wrote: “I don’t think I have ever quoted scripture to anyone”— and I can’t recall receiving such a scriptural message, before or since. The famous passage of 1 Corinthians 13:8 continues:

Love never faileth: but whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease; whether there be knowledge, it shall vanish away. For we know in part, and we prophesy in part. But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part shall be done away. When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

I recalled the passage was about love, but I didn’t realize it was also about prophecy—and its limits. My friend wrote in her e-mail: “I greatly admire your willingness to bear witness to your experiences and beliefs in such a radical and generous way. I will also say that I think the role of truth-bearer requires the purest of intentions. ‘Do it with love’ is good advice.”

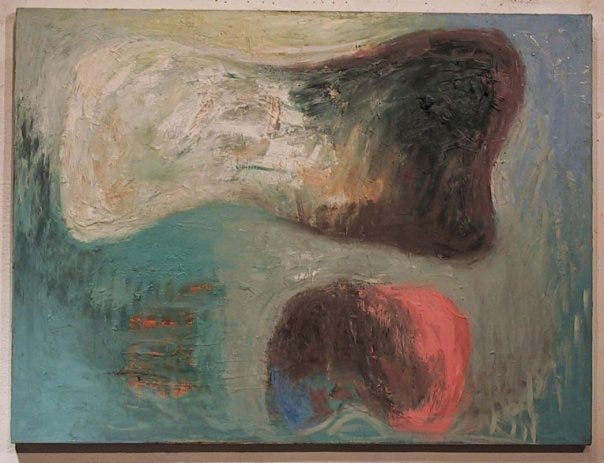

One of my father’s paintings from the 1990s.

Although my father met the magnate only once—at an Easter brunch organized by my partner, they sat side by side on the couch, discussing art and current events—in my mind they are linked, not only by their deaths a year apart, but by their lives. Although one was a wealthy entrepreneur and the other an impoverished artist, on a deeper level, they were like long-lost brothers. They were archetypal embodiments of the twentieth- century male—driven and proud, unyielding in their will and prodigious in their efforts. They were progressives, existentialists, with attitudes to life shaped by hard childhoods spent in the ruined landscapes of postwar Europe. Accepting modernism and the scientific worldview, they had rejected not only religion but any possibility of access to what the Austrian visionary Rudolf Steiner called “supersensible knowledge.” When I recovered the shamanic dimensions, I passed beyond the limits of thought that their lives and conditioning had imposed on them. To me, the conjunction of their deaths represented the closing of an era.

There is still time to join my new seminar, Crossing the Threshold: Realms of Consciousness Beyond Physical Death. Half-priced tickets for paid subscribers.

mind bending stuff Daniel, thank you. i have recently been compelled towards bible topics( i myself am too completely bible illiterate). but i think the times are drawing us towards the religious, and the truths held within these traditions. the psi stuff seems to be related. after admitting to some of closest realtions my interest in jesus and the bible(some of which reacted as if i had just admitted interest in heroin), i walked by a woman in a park talking on the phone saying, "we need to prepare to step up to support all these people from the new age(ha!) that are interested in jesus." also, when reading the lines of the Catholic mystic you cited, i had images of the final scene of 2001 flash through my head.

I was living in Phoenix on this day, twenty years ago. I shared a home at an international-level equestrian center with a horse trainer originally from New York. We were having breakfast and watching the news on TV before beginning the day's work with our show jumping horses and their owners. It was impossible to take our eyes off the horrific events taking place in Manhattan that morning. Then the cameras cut to the strike at the Pentagon. I couldn't move.

I had known since May of 2001 that something major was happening within the intelligence community. Completely unrelated to the equestrian field, my recent past had been ten years worth of connections in the realm of ufology, including the political-military-agency components that comprised many so-called conspiracy theories. In my quest to experience the source of information that often led to abbreviated conversations behind closed doors about the "third tier" or outright circular dialogues suggesting plausible denial scenarios, I spent some time in Washington, D.C., including attending lectures at the Institute of World Politics, a school for National Security. I had friendly chats with the instructors, including the head of the programs, Ken DeGraffenreid,

DeGraffenreid took an interest in my background with the UFO research field. His own history includes an impeccable career with the military and intelligence community:

"He has served as Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, Deputy National Counterintelligence Executive and Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs as White House Senior Director of Intelligence and Security Programs on the Ronald Reagan National Security Council. A retired Navy Captain, he also served on the staff of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. He has been a Senior Group VP of an R&D and systems engineering firm and VP of a high level policy analysis firm supporting sensitive USG programs in counterintelligence, telecommunications and security. He is Professor Emeritus at IWP, a graduate school in Washington, D.C. where he developed and directed the first MA degree in Intelligence and security studies to be offered in the United States."

Following my foray to IWP, DeGraffenreid kept me on his mailing list. Four months prior to the 9-11 attacks, I received an e-mail from him stating that the school would be closed indefinitely due to an expected return of senior personnel to government service. A gut feeling told me something very serious was coming. That morning of September 11th both confirmed and relieved the sense of foreboding. But what of the aftermath?

I could see the shock on my partner's face as we remained glued to the TV set, watching the towers burn, and then collapse. In the barn, horses were waiting to get out of their stalls, and clients were showing up for their lessons. Emotions running wild, we still had to walk out of the house, and into the stables. This was not a day for acting as though nothing terrible had happened. The atmosphere was already thick with foreboding and anxiety.

Horses pick up on tension, anger, and sadness in humans. Their responses vary according to their personalities and backgrounds, but it was already obvious they knew something was wrong. The nervous ones were pacing in their stalls. The tense ones laid their ears back. In the week that followed, far too many developed colic and some died. We lost one very nice black mare that we had just purchased a few weeks prior. The veterinary clinic nearby said they had never had so many colic cases in a short period of time. The collective human condition was hitting horses hard in the gut. It hit everyone in the gut. It was apparent that the world was never going to be the same.