In the first session of my seminar, Breaking Open the Head and the Psychedelic Renaissance, we tracked back through the early history of humanity’s relationship to visionary plants, looking at evidence for psychedelic use in Ancient Greece, South America, and India. We explored the archetypal model of the shaman as defined by religious historian Mircea Eliade in his groundbreaking book, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. We discussed initiation as a ritualized process found cross-culturally, until the birth of modern civilization. We looked at the psychedelic origins of contemporary folk archetypes like Santa Clause and the witch’s broomstick.

This Sunday, we will explore the relationship between the psychedelic experience and modernism as reflected by many artists, thinkers, explorers and anthropologists over the last centuries. We will also have a special guest: Brian Muraresku, author of The Immortality Key, his recent bestseller inspired by my book, Breaking Open the Head.

You can still join Breaking Open the Head and the Psychedelic Experience: Watch the recording of the first session, become part of the the community, and join the next three. Please use the code ‘AreYouExperienced’ for 1/3rd off the ticket price. More info and tickets here. Paid subscribers can access 1/2 price tickets for this and free entry for one-time seminars and discussions.

Below is a chapter from Breaking Open the Head, ‘Walking in Mysteries’, probing some of the themes of this week’s seminar:

WALKING IN MYSTERIES

What if the origin of culture, what Carlo Ginzburg called "the matrix of all possible narratives,” was the shamanic journey? Then art and literature, dance and theater would be elaborated or degraded forms of the original impulse to reach the "other worlds" through trance and ritual.

Perhaps modern culture and faith-based religion is a short-term experiment within the larger context of shamanism and its untold millennia of continuity: an experiment in turning away from actual visionary knowledge in favor of cathartic spectacles, symbolic codes, and the mimetic techniques of literature and film; in substituting personal knowledge of sacred realities with faith, and finally, in the secularized West, extinguishing faith entirely in favor of nonbelief in any spiritual dimension of human existence.

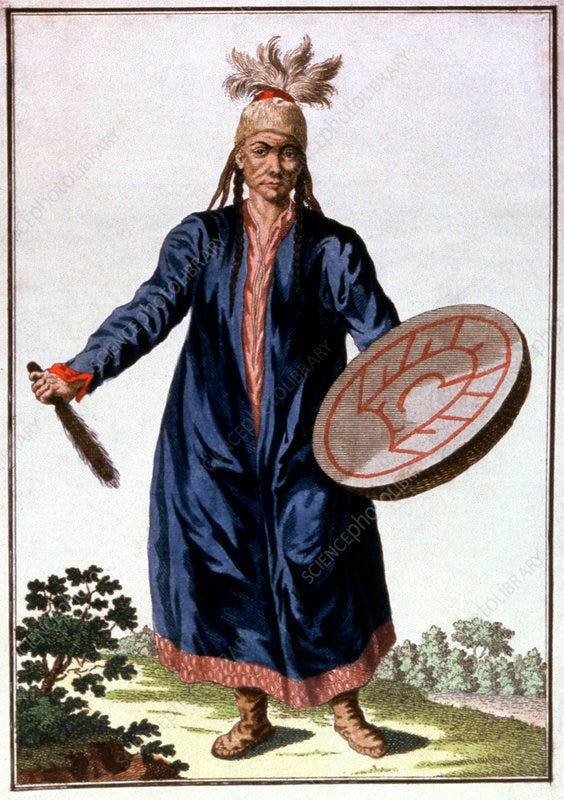

The "rediscovery” of shamanism is not just a New Age phenomenon. The Western world has made repeated attempts to understand shamanism, often seeking to reduce it to simple quackery. The process of forgetting and rediscovering, reevaluating and dismissing, shamanism has continued for centuries. From the sixteenth through the eighteenth century, explorers in Siberia and the New World wrote reports of jugglers, conjurers, and tribal sorcerers that were avidly studied by the intelligentsia of Europe. The tone of these accounts ranged from sneering attacks on fraudulent practices and shrill denunciations of devil worshiping, to objective and even compassionate studies of shamanic healing practices.

18th Century illustration of a Siberian shaman, fascinating for Europeans

“While some Europeans continued to ridicule what they considered public trickery and ignoble credulity, others began taking shamanistic practices very seriously,” writes the historian Gloria Flaherty in her book Shamanism and the Eighteenth Century. “Shamanism seemed to them to epitomize a grand confluence of ageless human activities the world over.” Flaherty suggests the evolving cult of the genius, the magic powers of enchantment attributed to Mozart or Goethe, arose out of Europe’s fascination with shamans.

The archetypal figure of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, Goethe amassed information on magic and ghosts, rejected Newton’s mechanistic view of nature, believing that nature was animated by spiritual forces. "We all walk in mysteries,” the poet and scientist wrote to a friend. "We are surrounded by an atmosphere about which we still know nothing at all. We do not know what stirs in it and how it is connected with our intelligence. This much is certain, under particular conditions the antennae of our souls are able to reach out beyond their physical limitations.” Goethe incorporated many aspects of the shaman archetype — contact with ghosts during Walpurgisnacht, drug-induced trance, journeys into the world of the dead, etcetera — into the figure of Faust, the modern magician.

In the nineteenth century, Romantic poets like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Edgar Allan Poe, and Percy Bysshe Shelley obsessively explored their dreams as a bridge between the unconscious and conscious mind. "I should much wish, like the Indian Vishnu, to float about along an infinite ocean cradled in the flower of the Lotos, and wake once in a million years for a few minutes — just to know I was going to sleep a million years more,” wrote Coleridge, whose most famous poem, “Kubla Khan,” was reconstructed from an opium revery.

Like shamans, the Romantic poets were practical technicians who investigated their own dreams and trance states, using drugs among other methods to probe the far reaches of the mind. They trained themselves to produce hypnagogic imagery — the semi-controllable hallucinations that can rise up just at the edge of sleep. Thomas De Quincey, who founded the modern genre of drug testimony with Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, described these visions as "heraldries painted on darkness.” The dream lyricism of the Romantics was an act of resistance to rational empiricism and the Industrial Revolution.

While the Romantics sought to linger in their dreamworlds, the Modernists explored the moment of awakening as the model for a new type of consciousness that could fuse rational and irrational processes. For writers like Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf, the effort made by the sleeper to awake from the dream served as a metaphor for the disconnect between the progressive scientific and social thought of their era, and the primordial, ritualistic slaughter of the First World War. "History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,” announces Stephen Daedalus, near the beginning of Ulysses, a book that includes a one-hundred-page play that takes place in "Night Town,” a transcript of a semi-coherent nightmare or ghost trip that reads like it was dreamt by the book itself.

In Search of Lost Time begins with Marcel Proust's protagonist lying in his bed, sorting himself out from confused and vivid dreams of the past. Proust's opening reveals the moment of waking up as a mysticaltransgression between the self and the not-self:

. . . when I awoke in the middle of the night, not knowing

where I was, I could not even be sure at first who I was; I had

only the most rudimentary sense of existence, such as may

lurk and flicker in the depths of an animal’s consciousness; I

was more destitute than the cave-dweller; but then the mem-

ory — not yet of the place where I was, but of various other

places where I had lived and might now very possibly be —

would come like a rope let down from heaven to draw me up

out of the abyss of not-being, from which I never could have

escaped by myself: in a flash I would traverse centuries of civi-

lization, and out of a blurred glimpse of oil-lamps, then of

shirts with turned-down collars, would gradually piece to-

gether the original components of my ego.

Each night, Proust's narrator journeys from psychic dissolution to self-possession, from dismemberment to remembrance. The image of a "rope let down from heaven" is akin to the shamanic motif of a ladder from the sky, leading between this world and the other realms. The vast undersea kingdom of sleep called into question the solidity of the waking reality: “Perhaps the immobility of the things that surround us is forced upon them by our conviction that they are themselves and not anything else, by the immobility of our conception of them.” The sickness that exiled Proust to a cork-lined room, out of contact with other human beings, in a kind of living afterlife, was like the shaman’s initiatory sickness and nervous disorder, his celibacy and his compulsion to separate from his tribe while exploring the spirit realms.

The Modernist writers and artists, consciously or not, borrowed elements from the shamanic archetype. Like tribal shamans, the artists saw themselves, in Ezra Pound’s phrase, as “the antennae of the race.” In a secular culture, they were the ones who journeyed into the land of the dead, who crafted images of an elusive sublime, who went into ecstatic states of inspiration. They believed their icons and testaments, like magic fetishes, contained the power to heal the culture’s spiritual maladies. Writers like Gertrude Stein, Tristan Tzara, or James Joyce explored private languages or languages explicitly made out of nonsense — similar to the shaman’s common practice of glossolalia, speaking in tongues, during trance. The shaman’s songs were taught to him by the spirits; the chants of the Modernist poet were expressions of alienation from a dehumanized and demystified world.

Two recent single-session seminars are now available for purchase:

ETs, UFOs,Psychedelic Encounters and the Collective Unconscious

Cosmic Thought, Cosmic Memory, Cosmic Dream: An Introduction to Rudolf Steiner