Robot Revolution?

Will AI unleash totalitarian dystopia or liberate us from bullshit jobs?

We stand at a peculiar historical juncture. We now possess technology that could fulfill humanity's age-old dreams of liberation. But these tools are being used against us — deployed to deepen our subjugation.

As AI evolves, companies are making massive cuts in their workforce. 30% of college graduates already struggle to find jobs in the U.S., as AI takes over many entry-level tasks. Microsoft and Meta recently laid off thousands of employees, with Microsoft cutting approximately 6,000 jobs—about 3% of its global workforce—primarily affecting software engineers and product managers . This shift coincides with AI's growing role in software development; Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella noted that AI now generates 20–30% of the company's code. This figure is expected to rise to 95% by 2030.

The impact of AI extends far beyond the tech sector: a report by CVL Economics estimates that generative AI will significantly disrupt 204,000 entertainment industry jobs over the next three years. This includes roles in animation and visual effects. A recent World Economic Forum survey found that 41% of employers plan workforce reductions due to AI. These developments reveal AI's accelerating impact across many industries, from software engineering to creative industries. As we reach Artificial General Intelligence or AGI, we will also see rapid advances in humanoid robotics, threatening millions of blue collar jobs.

As a large share of white-collar, cognitive, and even creative labor gets absorbed by AI, the traditional mechanisms of wage labor, consumer demand, and capital accumulation will unravel. Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, recently told Ezra Klein that in the next two years, AI systems will be capable of automating “at least half of all cognitive work.” This includes legal reviews, journalism, software engineering, and customer service roles. “We’re talking about the displacement of tens of millions of jobs, possibly more,” he warned. Corporate executives at publicly traded companies will have no choice but to lay off masses of people if AI improves their short-term bottom line.

With every passing week, it becomes increasingly obvious that the accelerated development of AI—including generative AI and foundation models like those developed by Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google DeepMind—poses a serious challenge to the traditional economic model of Capitalism itself. Right now, we lack for public debates about possible alternatives. We need these discussions — and we also need large-scale social movements that seek to address the problem at its root.

We are rapidly reaching an inflection point. Capitalism traditionally relies on a cycle in which labor generates income, income fuels consumption, and consumption drives demand for more labor. But if labor is no longer the central engine of value creation, that cycle collapses. The owners of the AI models—typically large technology firms or their shareholders—will accumulate exponentially more capital, while a large proportion of the population finds itself economically redundant, ruined and marginalized.

As MIT economist Daron Acemoglu has argued, “the problem is not just job loss—it’s the decoupling of productivity growth from shared prosperity.” In this trajectory, productivity gains no longer translate into better living standards for the majority.

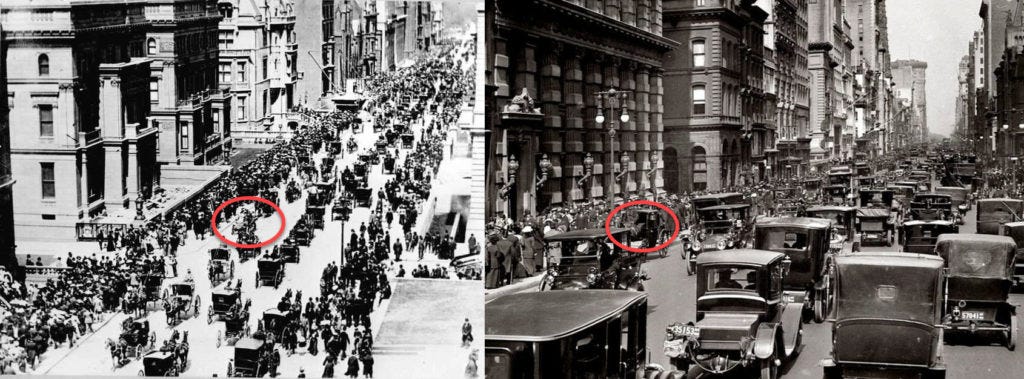

Check out these two pictures from Broadway in New York City. They were taken just thirteen years apart. The first one, from 1900, shows a street of horses and horse-drawn carriages (with one car). The second one, from 1913, shows the same street with almost all cars (only one horse). If we don’t address this now, AI has the potential to do to our human family what the car did to the horse a century ago.

Some theorists believe the AI shift is already ushering in a new post-capitalist system they call technofeudalism. Economist Yanis Varoufakis believes tech oligarchs function like digital “feudal overlords”: They rent us access to their massive algorithmic ecosystems. They control and monetize our data. They can sell it to unscrupulous political operatives who seek to manipulate us with disinformation, as Meta did in 2016, when Cambridge Analytica amassed 5,000 data points on every adult in the U.S. and used it to tilt the election.

Over the past decade, the wealth of tech magnates like Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg has surged drastically, far outpacing global economic growth and exacerbating wealth inequality. In 2015, Bezos's net worth was approximately $47 billion; by 2025, it had soared to around $242.4 billion, marking an increase of over $195 billion. Similarly, Zuckerberg's wealth grew from about $33.4 billion in 2015 to approximately $209.6 billion in 2025, an increase of over $176 billion. Collectively, the total wealth of billionaires worldwide more than doubled from $6.3 trillion in 2015 to $14 trillion in 2024, a 121% increase, while the global economy grew at a much slower pace. This concentration of wealth among a select few reveals the unsustainability of our current economic model.

Despite amassing incredible wealth, Bezos just switched the rules on E-books sold on Amazon’s Kindles to squeeze out more money. People no longer own the E-books they buy from Amazon. They rent them in perpetuity. This portends deeper shifts ahead, as the tech oligarchs continue to amass and concentrate capital, and we are reduced to digital sharecroppers farming their empires. In The New Republic, Thom Hartmann identifies “excessive hoarding” as a type of mental illness that, unfortunately, has ruinous effects on society as a whole. Michael Parenti notes:

Wealth becomes addictive. Fortune whets the appetite for still more fortune. There is no end to the amount of money one might wish to accumulate, driven onward by the auri sacra fames, the cursed hunger for gold.

So the money addicts grab more and more for themselves, more than can be spent in a thousand lifetimes of limitless indulgence, driven by what begins to resemble an obsessional pathology, a monomania that blots out every other human consideration.

Our immediate crisis of economic structure calls for a paradigm shift. As AI destroys jobs faster than it creates new meaningful ones, while wealth becomes increasingly concentrated in the hands of those who own or control the platforms, then traditional solutions like retraining or re-educating people will be woefully insufficient. We are not just facing a labor market disruption—we are confronting the breakdown of the social contract itself.

“We are no longer selling our labor or our products—we are just allowed to exist, conditionally, inside their digital enclosures,” Varoufakis writes. We can already see, in this system, that wealth tends to accumulate vertically instead of circulating horizontally. Karen Hao, in Empire of AI, calls this “data colonialism.” She believes we are seeing a return to many of the worst aspects of colonialism, now given a high-tech makeover.

Some propose Universal Basic Income (UBI) or “data dividends” as transitional policies, but these require redistribution mechanisms that existing capitalist democracies seem unprepared to implement at scale. Certainly, in the United States, the current federal government is intent on reducing social services and removing protections for workers and consumers, such as fraud protections, in order to increase profit for corporations and the wealthy.

The underlying issue is philosophical as well as economic. We have to ask ourselves: What is the purpose of human life, particularly when machines can outperform us in most domains? If AI drives down the marginal cost of cognition to near-zero, then our foundational assumptions around value, merit, and productivity lose meaning. However, most people actually prosper when they are freed from the compulsion to work in order to survive.

As early as 1930, John Maynard Keynes foresaw this possibility, predicting in his essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren that technological advancement would eventually allow us to transcend the need for labor and enter a post-economic society. “For the first time since his creation,” Keynes wrote, “man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem—how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure…to live wisely and agreeably and well.” We are rapidly approaching that critical threshold.

The question now is whether we can evolve our traditional institutions or build new institutional structures quickly enough to meet the challenge of mass job loss and extreme concentration of wealth and power. If we can’t, we risk sliding into a form of digital authoritarianism or mass precarity, while still pretending to be innovative. This, obviously, is not going to happen on its own: It requires sustained pressure and large-scale campaigns against the tech overlords, along with a definitive plan and vision for the alternative.

Capitalism has been playing this trick on the people for many years now. Back in the 1950s in the U.S., it was normal for the husband in a traditional nuclear family to be the only working member of the household. The family would still be able to buy a house and send their children to college. More recently, both parents need to work and often they still slide into debt. As corporations and investors profit, the “American Dream” has become a distant memory for most people. This has led to mass frustration and anger that gets misdirected, away from class politics, into cultural and religious issues.

Unless new models of economic life, ownership, and governance are defined and actually implemented soon, we will find ourselves trapped in a highly stable totalitarian regime with massive powers of surveillance and military repression. According to The New Republic, “The Trump administration is collecting data on all Americans,” working with Peter Thiel’s company Palantir. The magazine fears “the government is putting together a database to wield surveillance powers over the American public.”

So what are the answers?

Mainstream liberals like the New York Times’ Ezra Klein promote the idea that we can essentially preserve the current system of government by fixing zoning laws and otherwise tinkering around the edges. This seems very naive to me, considering the massive transformations of social and political system currently underway from the Right. Personally, I think we will have to consider far more radical possibilities to address the massive social dislocation that AI will unleash, and, also, build a new kind of social movement that proposes a desirable enough vision of the future that it inspires and incites many millions of people to act together toward that shared vision.

Personally, I think our answers are more likely to be found in essays like Oscar Wilde’s amazingly prescient The Soul of Man Under Socialism, as well as Piotr Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid, and Murray Bookchin’s The Ecology of Freedom. What do these thinkers propose? Can we synthesize their ideas to draw a blueprint for our future?

Writing in 1891, Oscar Wilde envisions a radical transformation of society that would render enforced labor obsolete and liberate the individual to pursue artistic and spiritual development. He critiques the charity and reformism of his time as treating symptoms rather than causes, writing, “Their remedies do not cure the disease: they merely prolong it. Indeed, their remedies are part of the disease.” Wilde’s “socialism” seeks more than economic freedom: He calls for the emancipation of the human personality from the degradations of property and compulsory work. He imagines a future society where machines perform all necessary labor and “nobody will waste his life in accumulating things, and the symbols for things. One will live.”

Wilde point towards a post-scarcity world in which technology frees humanity rather than enslaves us. He demands a revolutionary socialism of the artist and aesthete instead of the bureaucrat and accountant. What is amazing is that, if AI could be utilized sanely and properly, we would be on the precipice of creating that post-scarcity world that Wilde imagined. Aaron Bastani proposed a similar model in his recent book, Fully Automated Luxury Communism.

Peter Kropotkin, writing in Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), offers a scientific and ethical foundation for a cooperative society. He challenges the Social Darwinist view of evolution as inherently competitive, arguing instead that cooperation is the primary force in both human and animal survival.

For Kropotkin, mutual aid is the empirical basis of evolution and the means for organizing a non-hierarchical, decentralized society. In his anarcho-communist framework, voluntary associations replace coercive institutions. Resources get distributed according to need, not market exchange. He imagines “communal possession of the instruments of production” and criticizes the wage system as a form of slavery. His model presumes that human nature is not fixed in greed but is protean, responsive to conditions of solidarity. Wilde, similarly, saw human nature as something that changes continuously.

Murray Bookchin, in The Ecology of Freedom (1982), unifies ecological awareness with social liberation through what he calls “social ecology.” He critiques both capitalism and centralized Marxism for perpetuating domination—over nature, over women, over the working class—by failing to examine the deeper patterns of hierarchy embedded in civilization itself. He traces the roots of domination not just to capitalism but to the earliest systems of gerontocracy and patriarchy, arguing that true liberation must dismantle all forms of hierarchy.

Bookchin proposes a decentralized, directly democratic polity organized around communes and confederations, using technology in a rational, ecological, and human-scaled way. “What renders the present crisis so unique is that society now has the technological means to eliminate toil, poverty, and material insecurity,” he writes. “The failure to do so stems from social relations, not technical limitations.” His project aims not merely at sustainability but at the flourishing of autonomous, ethical individuals within a richly interconnected world.

If we synthesize Wilde, Kropotkin, and Bookchin, we arrive at a radical blueprint for a post-capitalist, post-domination society rooted in voluntary cooperation, ecological balance, and the cultivation of the individual spirit. This would be a society where the individual is no longer deformed by labor or property, but is free to become what he or she is. Wilde notes that, in the past, artists were generally those with an inheritance and a trust fund, who had the time and freedom to cultivate their unique essence and creativity. He wanted everyone to have that opportunity in the future — whether or not they became artists or just spent their time with their family or exploring what he called “cultivated leisure.”

Kropotkin shows how mutualism and decentralized organization are basic to all life, grounding these models of reciprocity in biology and anthropology. Bookchin melds a systemic analysis of hierarchy with a concrete political vision of “libertarian municipalism.” Technology, including AI, and ecology can be harmonized through participatory democracy. Together, these thinkers converge on the necessity of dismantling the deep structures of domination and control—economic, psychological, and ecological—that are the invisible undergirding of modern life.

Ironically, if we can decouple the AI revolution from capitalist and technofeudalist modes of control, it could provide the necessary conditions to fulfill Wilde’s dream of a life beyond toil, as well as Bookchin’s vision of a world without domination or excess private property. But this would require a massive shift of social values away from competition and accumulation toward autonomy, community care, and creativity.

AI could allow us to redefine and embody new dimensions of human freedom where we learn to co-create and evolve ourselves in partnership with technology as well as nature. At this point, whether we rise to this challenge depends entirely on us.

Good analysis. Public debate is going to be difficult because most Americans have no clue about the force and rapidity of the megatrends you’re pointing out. Congress is certainly clueless as well. Either that or they're ducking the issue entirely. The only social movement that I can think of at the moment that makes any sense is not to use AI as a form of protest. That of course is highly unlikely to happen because we're all are being groomed and herded toward its use, like it or not. AI is showing up in many of our Web-based resources and other digital systems including search which will soon be highly AI-dependent. There seems to be no escape or immediate solution on the horizon which means that our fundamental human agency is being slowly eroded and stripped away.

Very interesting points about Bezos and Kindle. And the Hartman quote. In this context, it also seems fair to ask why Zuckerberg is building his incredibly expensive bunker. This suggests a survivalist mentality of take the money and run while the ecology of planet Earth and the stability of longstanding economic systems get trashed. As a sidenote, I have never believed that UBI could be fairly implemented as it seems to have originated with the WEF crowd and just seems like some kind of high-end welfare system, bribe, or consolation prize for a wider swath of disadvantaged economic classes.

"But if labor is no longer the central engine of value creation, that cycle collapses. The owners of the AI models—typically large technology firms or their shareholders—will accumulate exponentially more capital, while a large proportion of the population finds itself economically redundant, ruined and marginalized."

This is just primitive accumulation in a new era. Ths is what happened with the enclosures between the 16th century and the 19th century. During this period of time, the Rates provided UBI for anyone who could not find work. Why were the Rates ended? They were ended because of the Speenhamland system:

"Under Speenhamland, society was rent by two opposing influences: the one emanating from paternalism and protecting labor from the dangers of the market system; the other organizing the elements of production, including land, under a market system, and thus divesting the common people of their former status, compelling them to gain a living by offering their labor for sale, while at the same time depriving their labor of its market value. A new class of employers was being created, but no corresponding class of employees could constitute itself. A new gigantic wave of enclosures was mobilizing the land and producing a rural proletariat, while the “maladministration of the Poor Law” precluded them from gaining a living by their labor. No wonder that the contemporaries were appalled at the seeming contradiction of an almost miraculous increase in production accompanied by a near starvation of the masses. By 1834 there was a general conviction—with many thinking people a passionately held conviction—that anything was preferable to the continuance of Speenhamland. Either machines had to be demolished, as the Luddites had tried to do, or a regular labor market had to be created. Thus was mankind forced into the paths of a utopian experiment."

Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (pp. 84-85). (Function). Kindle Edition.

What we are seeing now is a continuation of enclosures. Now, it is not just land, but people's bodies, words, etc., that are being enclosed. Social media is a form of enclosure of the commons—even Substack.

The only way is through, and the only way through is the creation of real communities of flesh and blood people, not abstracted relationships through computer screens, the dominant mode of soclal interaction today. If one wishes to build a new mode of production, what could that possibly be? The challenge of the mass disruption (read primitive accumulation) that may be caused by AI is huge and will not be solved by UBI.

Silvia Frederici asks:

"tWhat do we mean by ‘anticapitalist commons’? How can we create a new mode of production no longer built on the exploitation of labor out of the commons that our struggles bring into existence? How can we prevent the commons from being co-opted and, instead of providing an alternative to capitalism, becoming platforms on which a sinking capitalist class can reconstruct its fortunes?"

Federici, Silvia. Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons (Kairos) (p. 86). (Function). Kindle Edition.

People who have no role in capitalist value creation still can work. They just can't work in a capitalist system. They need to create a different means of production. They may have to return to subsistence farming to feed themselves and their families etc. They can still create value. They just won't be able to sell it on Amazon or trade shares of it.

And what if we choose to devalue the products of the technocrats by refusing to use them, if it comes to that? Value is only produced by human beings and can only be used by human beings. Machines themselves create no value and use no value. Their activity is meaningless without a human context to give it meaning. If AI causes the collapse of the economy by throwing millions out of work, who have no income and no means to participate in the economy, then the technocrats havw hoisted themselves on their own pitard. Who cares if there are a million robots in Tesla factories making trucks to carry goods if there is no one to buy them?

Resistence will be found in communities nearby, not flung across the world. Fairly soon the walls are going up, travel will be restricted, and we will have only our neighbors to rely on. The era of state revolutuons is over. We can only resist though developing commons together.