Slavoj Žižek's Christian Atheism

Can "Christian atheism" and "real materialism" save the West?

Apparently I am writing a series on contemporary icons or cultural archetypes: Last week, I sought the meaning of the Taylor Swift hyperobject. This week, I am hunting a bird of a different feather: Slavoj Žižek, notoriously convoluted Slovenian political philosopher. I saw Žižek speak with Cornell West last week at the New School on the subject of “Politics and Theology” (recording is here). I found their talk discouraging, almost alarming, for reasons I will explore. The event promoted Žižek’s latest book, Christian Atheism: How to Be A Real Materialist, written in his characteristically digressive style, which I am halfway through. I’ve been reading him, off and on, for more than thirty years. He’s produced a convincingly massive pile of tomes.

Žižek defines himself as a Lacanian Hegelian Communist who admits a strange penchant for Stalin. I went through a Lacanian phase in college, inspired by a young Scottish literary professor who resembled Bette Davis, drank with her students after class, and wore vintage dresses. She was a rising star but, tragically, succumbed to alcoholism at the age of thirty-two. She took a teaching job at NYU where she proceeded to drink a bottle of whiskey a day (a bit of Internet research excavated this remembrance of Rena, written by my old friend Josefina Ayerza, editor of lacanian ink). I couldn’t help finding that my teacher’s tragic end cast a pall on Lacanian ideology, with its funny coinages such as “petit objet a” and “sujet supposé savoir” (“the subject supposed to know”), and the sense of an underlying, inescapable lack or schism within Being itself.

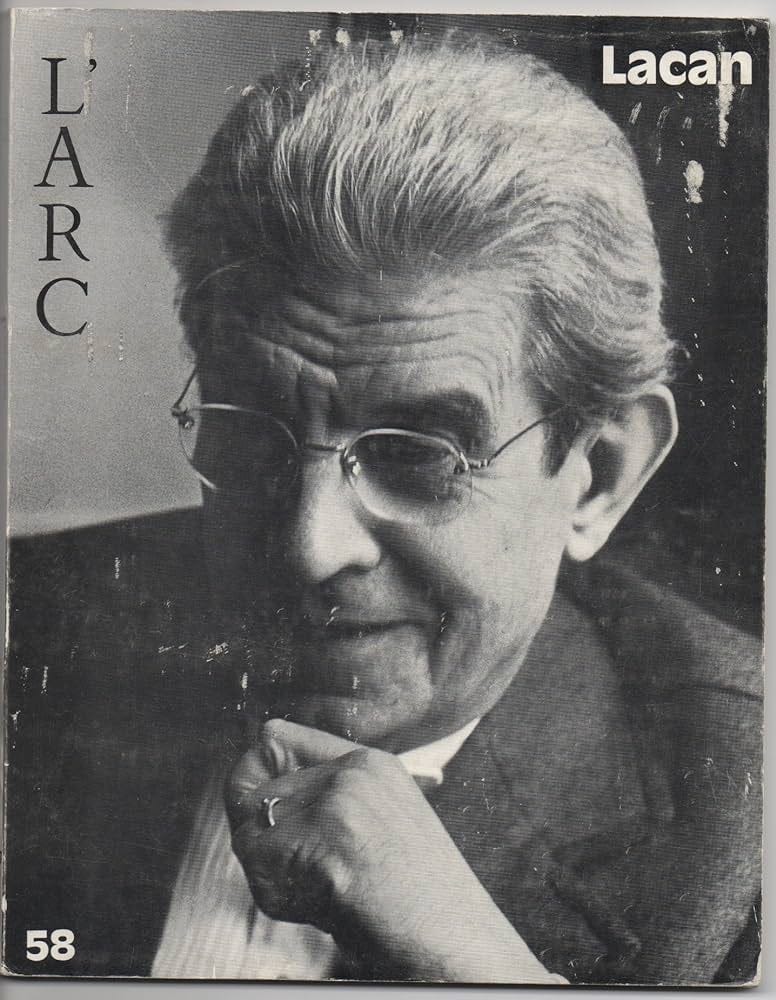

An imposing figure in French postwar intellectual life, Jacques Lacan radiated hawk-like glamor and regality. As a psychoanalyst, he was infamous for cutting off his patients in suddenly-declared “short sessions.” During appointments with patients, Lacan would often ignore them by reading the newspaper or counting stacks of French francs at his desk – money, he told them, he had accumulated through their patronage – while they spilled their guts. It is more than rumor that “a large number of Lacan’s patients killed themselves.” As one might expect, this caused “sharp suspicion of his work among many in the analytic world.”

Lacan’s writing – somewhat akin to Žižek’s – is fascinatingly difficult. I come from a tradition of writing and thinking that prioritizes being clear and comprehensible. Except in poetry, I write to be understood – to make difficult things easier for myself and other people to understand. I do recognize that the difficult style of certain philosophers and thinkers is inextricably woven into their way of thought, and cannot be easily simplified or parsed – Nietzche and Heidegger come to mind. But I find this a high bar. For the vast majority of writers, clarity is far preferable, as a service for readers and for thinking, in general. I admit to a suspicion that excessive stylistic difficulty is often a kind of cover-up for weak argumentation, or a means of conveying an imposing vibe of intellectual superiority: This text is not meant for just anyone, the ordinary Joe, but only for those who form an intellectual elite, a select coterie. A lot of art criticism has this insular, cult-like quality, meant to imbue the work with (cultural but also financial) value.

When I read Žižek, I get a feeling similar to whirling around in a washing machine or Merry-Go-Round: a kind of destabilizing turbulence that is seductive for those (like me) who are susceptible to this kind of intellectual overwhelm, where abstract theories from a maze of thinkers alternate with anecdotes, pop cultural references, and dirty jokes. He is, in his own strange way, an entertainer, a philosophical comedian – that is part of his charm. Christian Atheism contains early chapters on Buddhism and quantum physics, two subjects that also fascinate me. I thought I would focus on these chapters, as I utterly disagree with what I am able to pin down of his ideas.

Here, one might ask: What’s the point? (Or, similarly, Who cares?)

The real battle, for me, is to budge, nudge, and eventually smash apart (shouldn’t we, as Nietzsche put it, philosophize with a hammer?) the atheist and materialist foundation of the contemporary Left, which Žižek, who remains a major figure in Leftist thought, exemplifies. There is much I admire about him. For instance, I wrote appreciatively about another recent book of his, Hegel in a Wired Brain, here. I love Sophie Fienne’s two-volume documentary, A Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, on his film theory (I recall his point that the catastrophe of the sinking of the Titanic “saved the world” from the far worse potential catastrophe of the Leonardo di Caprio and Kate Winslet characters falling in love across social classes). I find him a necessary, archetypal figure, but problematic and, in crucial ways, regressive.

Regressive partly because, I believe, materialism ( even, in a traditional sense, atheism) is an obsolete paradigm which we must discard. My hope for the future is a “resurrected” Leftism that is esoterically infused and mystically empowered – while fully integrating empiricism, science, and rational inquiry. Only such a resurrected Leftist movement (it may come too late, but it will come) has the potential to not only assimilate the traditional religious structures but, eventually, unify and elevate our human community. Such a movement could help us build a new, post-Capitalist infrastructure based on mutual aid, solidarity, trust, and transparency (what the Catholic visionary Teilhard de Chardin anticipated as the Noosphere), with a much lower expenditure of energy and resources.

There – I have put my cards on the table.

In the past, I’ve noted that any cultural figure who comes to prominence does so because they reflect the current level of (psychological, intellectual, moral) development in their particular constituency. The philosopher Timothy Morton (Hyperobjects) sees in Žižek’s often-expressed “hostility” to Buddhism “a narcissistic woundedness so painful that it seems better to paint the whole world with its raw colors than examine itself, even for a second.” I think this is true.

To be honest, I find elements of this “narcissistic woundedness” in myself. I can feel how that hurt part of myself easily identifies, finds a kind of grim solace, in Žižek’s particular whirligig style of philosophizing. I think this is the case across a swathe of contemporary Leftists, self-identified as outcasts, pained by the horrifying impacts of the Capitalist megamachine on the human hive-mind and the planetary ecology, while trapped in the spell – the “rebel yell” – of atheist materialism (the spell I am trying to break).

One theory I have is that post-Existentialist / materialist thinkers such as the French Post-structuralists created an exhilarating, mystified language to give some of the allure of cultic religiosity to an otherwise dreadfully nihilistic worldview which sees consciousness as a purely accidental byproduct of brain complexity and denies any possibility of soul, spirit, or any kind of consciousness existing after death. The hyper-complexity – which can be great fun, as in Derrida, Barthes, or Iragary – hides the barrenness of vision, the forfeiture of transcendence, behind the project.

Žižek puts forward his “stance of Christian atheism” as, impressively, the “only” way to “save the Western legacy from its self-destruction.” He has said this for decades now. As with many of his ideas, I find it unclear if this is meant as comedy or somewhat seriously. He reinterprets Christ’s crucifixion – God’s temporary forsaking of Christ on the Cross – as a repudiation of anything beyond or transcendent to our human realm:

“What dies on the cross is not an earthly representative or messenger of god but, as Hegel put it, the god of the beyond itself, so that the dead Christ returns as Holy Ghost which is nothing more than the egalitarian community of believers… This community is free in the radical sense of being abandoned to itself, with no transcendent higher power guaranteeing its fate.” I doubt many theologians would agree with this interpretation.

Žižek reiterates: Christ’s sacrifice “stages the meaninglessness of a sacrifice and thus releases us into our freedom. In other words, Christ is not a mediator between god and man which brings about their reconciliation: his dead body is rather a monstrous frozen monument to the lack of any transcendent agent safeguarding our fate… in his passive suffering, he gives body to the fact that “there is no big Other,” that something is terribly out of joint in our world.” For Žižek, Christ’s sacrifice still has cosmic significance, but only in a negative sense: It reveals atheist materialism – the abyss or lack that constitutes reality – as our ontological basis. Obviously, this is not how Christians or occultists understand Christ’s sacrificial act.

I won’t dive too deep into theological disputes here. I have my own interpretation of Christ’s life and sacrifice, which owes a great deal to Western esoteric and occult philosophers including Rudolf Steiner, Gurdjieff, and Dion Fortune. Shorthand: I find Žižek’s interpretation completely wrong.

Obviously I don’t believe Christ “died for our sins,” or that we absolve ourselves of “sin” by faith in his Divinity. I suspect Christ – as a spiritual being and principle – did incarnate on Earth with a mission and purpose: He showed us a model for how to live in this “matrix-reality” (Gnostic perspective) while reconciling other dimensions and “higher” planes with our words and deeds. For Steiner, Christ’s incarnation did, in a sense, give humanity a new threshold of individual sovereignty: We have the freedom, for example, to pursue an occult or a materialist path. But for Žižek, there simply cannot be other dimensions, spiritual realms, or anything occult or “beyond.” His materialism is an anchor to which he must cling.

In Pain, Sex, and Time, Gerald Heard made an astute observation: Centuries ago, during the Enlightenment and after, it was agonizing for people to give up their cherished religious beliefs for the desacralized scientific / materialist worldview. This battle was still fought over the course of the Twentieth Century and even recently, through thinkers like David Dawkins (The God Delusion), Daniel Dennett (Breaking the Spell), and Sam Harris (The End of Faith). Growing up in New York City in the 1970s and 80s, I hardly met anyone with the slightest smidgen of religious faith or mystical access. Materialism, atheism, was the only ontological game in town, unless you were some kind of idiot. Our mainstream progressive institutions (The New York Times, Harvard, etc) still maintain this stance, more or less. Today, corporations, scientists, and journalists make an ongoing effort to assimilate the psychedelic experience into this reductive physicalist worldview (the “default mode network,” etcetera), suppressing the commonly experienced psychic, paranormal, transpersonal, and infra-dimensional revelations.

Today, the materialist worldview is obsolete, as we will discuss (and I explored here). But people cannot relinquish or question it because materialism/atheism has become a core part of their identity and ego structure. It would be too painful for them – and make them look too foolish – to concede the point. Heard makes the point that, just as it was very painful to make the shift from seeing the universe as replete with transcendent meaning and purpose, it is equally painful to make the shift in the other direction. At the same time, while materialism is the entrenched establishment faith, materialists/atheists still tend to perceive themselves as existentialists, holding the outsider/rebel/cool perspective, with anybody following what Žižek calls “theosophy” (New Age-ism and its variants) unworthy of serious intellectual consideration.

As an aside, I find it interesting that, despite Žižek’s avowed commitment to (Communist) revolutionary struggle, he seems to defend his particular version of the Western or Anglo-European project, which he connects to Christian atheism, which he called, in a 2006 New York Times Op-Ed, “one of Europe's greatest legacies and perhaps our only chance for peace” (although Communist Russia and China were atheist societies, yet committed mass murders on vast scales). In Christian Atheism, he notes, “Europe is no longer able to remain faithful to its greatest achievement, the Leftist project of global emancipation.” While Europe is assailed for allowing slavery, Žižek argues, the “Western European nations… were the only ones which gradually enforced the legal prohibition of slavery. To cut it short, slavery is universal, what characterizes the West is that it set in motion the movement to prohibit it – the exact opposite of the common perception.”

I don’t have the full geopolitical scope to know if this is the case, but I would say – as I am sure Žižek knows – the West supplanted out-right slavery with other technocratic and financial practices that fulfilled, more or less, the same aim with less moral taint. For example, we have used economic and military methods (Third World debt structures, assassinations, coups against Democratically leaders, and so on) to compel brutally underpaid labor and resource-extraction around the world. As one almost random example, chocolate farmers in the Ivory Coast, in an industry dominated by a few American companies (Hershey’s, Nestle’s), get paid 78 cents a day for difficult, dangerous labor. We find variants of this — efficient, remote-controlled techniques of Western domination – around the world, although other, non-Western empires are now catching up to us in their practices. Anyway, it is difficult to defend much about the West’s historical project at this point in time, although I admit I feel the same inclination

Žižek’s Buddhist Fantasies

For Žižek, following Hegel and Lacan, reality is built around a core lack, crack, or gnawing insufficiency. He writes:

“Doubt” is located in reality itself, in the sense that there is no “knowledge in the real,” that reality (partially) ignores its own laws and doesn’t know how to behave – there is a crack in reality which makes it non-totalizable, “not-all,” but everything that we project beyond this gap is our fantasy formation. The only way to avoid agnostic skepticism is to transpose this gap into reality itself: the gap we are talking about is not the gap that separates reality-in-itself from our approaches to it but an impossibility which gapes in the heart of reality itself.

This is not, in essence, the perspective of Buddhism. This makes it an ideological threat to the model he seeks to maintain, which is why he keeps attacking it. Along with this ontological question about the underlying nature of reality itself, Žižek also dislikes Buddhism for having an apolitical or amoral stance that, ultimately, he believes, deprioritizes political action when compared to the individual, inner quest for realization.

This essay has gotten long! I will pause here, and return to it next time. As always, I look forward to your thoughts, ideas, and other comments.

I did my grad work at NYU 1984 - 94 when poststructural theory was all the rage in my field, comparative literature. As I recounted in my memoir, What I Forgot...and Why I Remembered, it took me years to recover from that heavy-handed indoctrination into what I eventually came to recognize as elitist mental masturbation. I didn't realize that Zizek was anti-Buddhist, but it doesn't surprise me. Anything with depth & heart would be too "soft" for him. I am not a fan of "philosophizing with a hammer"; this was Nietzsche's response to his own profound trauma. I prefer philosophizing microrrhizally, which I appreciate in your work, Daniel. You are radically inclusive with so many different roots & shoots nosing out through the terrain. Always interesting to see what you'll turn up next.

enjoyable read my man, but couldn't help but wonder how many folks (still) possess the background in intellectual history to track half the references you're making? Our current hyper-presentism has erased the "generally educated in the liberal arts" middle ground of the New Yorker/Atlantic reader of the 90s. Erik Davis and I were just assessing this simple fact--anything that's intriguing enough to write about is generally a hop and a skip from consensus reality, but those stepping stones are now underwater in the deluge of AI Slime and Digital Drivel. So anything you'd want to say (like contrasting Zizek's materialist atheism with a more mystic Christic gnostic version) gets lost in translation. Better (I think for all of us of a certain GenX persuasion) to write more like Ryan Holliday resurrecting the Stoics--presume nothing, explain everything, popularize/simplify most things. Keep writing regardless, there's at least some of us following along ;)