Now I am in Brussels: A city I know almost nothing about, where I know virtually no-one.

In Brussels, it is hard not to think about the Surrealist artist Rene Magritte, as his images are everywhere. Visiting the Magritte Museum at the center of town, I felt resonance between Magritte’s paintings — with their nod to old-fashioned commercial inducements — and the vaguely uptight Belgian bourgeois vibe. I would say Magritte is a minor artist, even though he had a major influence in art, advertising, and even philosophy (Michel Foucault wrote a book based on Magritte’s famous verbal refutation scrawled beneath the image of a pipe).

Magritte’s art, like other modern and postmodern oeuvres, extracted enough poetry out of the world of bourgeois commodities to satisfy the cognoscenti of his time. I suspect, in retrospect, it was a social function of the Surrealist movement to infuse the world of commodities, manufactured things, with a magical, absurdist aura. This postponed a cultural reckoning with Capitalist nihilism — a reckoning we still postpone, today.

Perhaps it is no longer cool to say this, but strange cities (even slightly boring ones) still excite me. If I am honest, I find most countrysides and rural areas to be tedious. I suppose this reflects my urban bohemian pedigree. I identify with Baudelaire’s notion of the flaneur, who “saunters around observing society,” flitting through urban landscapes like a phantom, on a quest for peak aesthetic moments and odd disjunctions.

For the roving flaneur, a city like Brussels reveals centuries of interwoven cultural practices, historical processes, and the jumbled-together lives and dream-worlds of so many people living in tight proximity. Like Paris or London, Brussels approximates the highest evolution of today’s post-industrial techno-culture into a sleek, well-functioning mega-machine undergoing constant fine-tuning. For its middle class, a city like Brussels is, in its own way, a kind of paradise, when we consider it from the perspective of someone living centuries ago.

What primarily differentiates the humdrum ambience of a metropolis like Brussels from the ecstatic infinite Now of Burning Man’s Black Rock City is that, here, people do not consciously realize they are living in a human-concocted utopian project. They don’t welcome every person as a variant of themselves, seeking joy and experimenting with consciousness, improvising, moment by moment.

People — here and in other big cities — have imbibed the notion that life is meant to be serious. We must keep producing, working — to survive and to fulfill somebody’s notion of progress. They do so with fixed intent, with serious faces. They are, like Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous Parisian waiter, playing a game they forget is a game:

Let us consider this waiter in the cafe. His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes toward the patrons with a step a little too quick. He bends forward a little too eagerly; his voice, his eyes express an interest a little too solicitous for the order of the customer. Finally there he returns, trying to imitate in his walk the inflexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tight-rope-walker by putting it in a perpetually unstable, perpetually broken equilibrium which he perpetually re-establishes by a light movement of the arm and hand. All his behavior seems to us a game… He is playing, he is amusing himself. But what is he playing? We need not watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter in a cafe.

Very few people want to be startled awake from the dream of ordinary life in late-stage Capitalism. If anything, they seek to immerse themselves in it more deeply.

I like visiting cities where I have no particular affiliations or human connections because I more easily appreciate the city as a gigantic human beehive, a “scaffold for living systems,” as designer John Todd called them.

As I stroll around, I think: This is the threshold we’ve attained as a species. We go from bistro to cafe, from museum to nightclub. We consume French fries, beer, and entertainment spectacles. We have these various yet, at the same time, homogenous adventures altogether. As myriad strangers linked by proximity, we effortlessly dodge the ever-unspoken question: “What’s the point?”

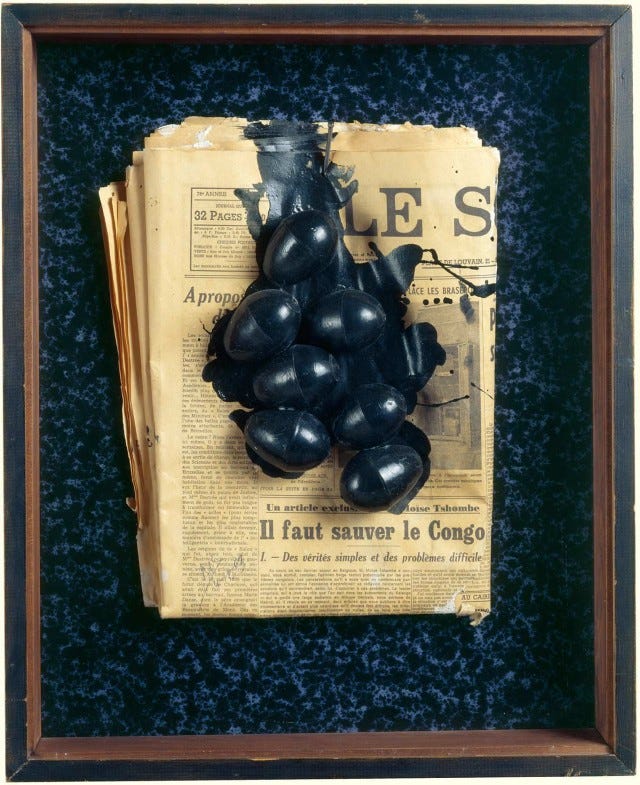

Wealthy European capitals like Brussels conceal beneath their well-heeled surfaces the colonialist history of domination and exploitation which created much of their splendor. King Leopold II’s cruel domination of the Congo from the 1880s decimated half that country’s population to extract ivory, rubber, and other raw materials, filling Belgium’s coffers. There is still a large African population here, a living continuity of that history.

In The Culture of Cities, Lewis Mumford defined the city as collective art work and dramatic spectacle: “One may describe the city, in its social aspect, as a special framework directed toward the creation of differentiated opportunities for a common life and a significant collective drama.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.