"The Honeyed Nectar of the True Soul-Life"

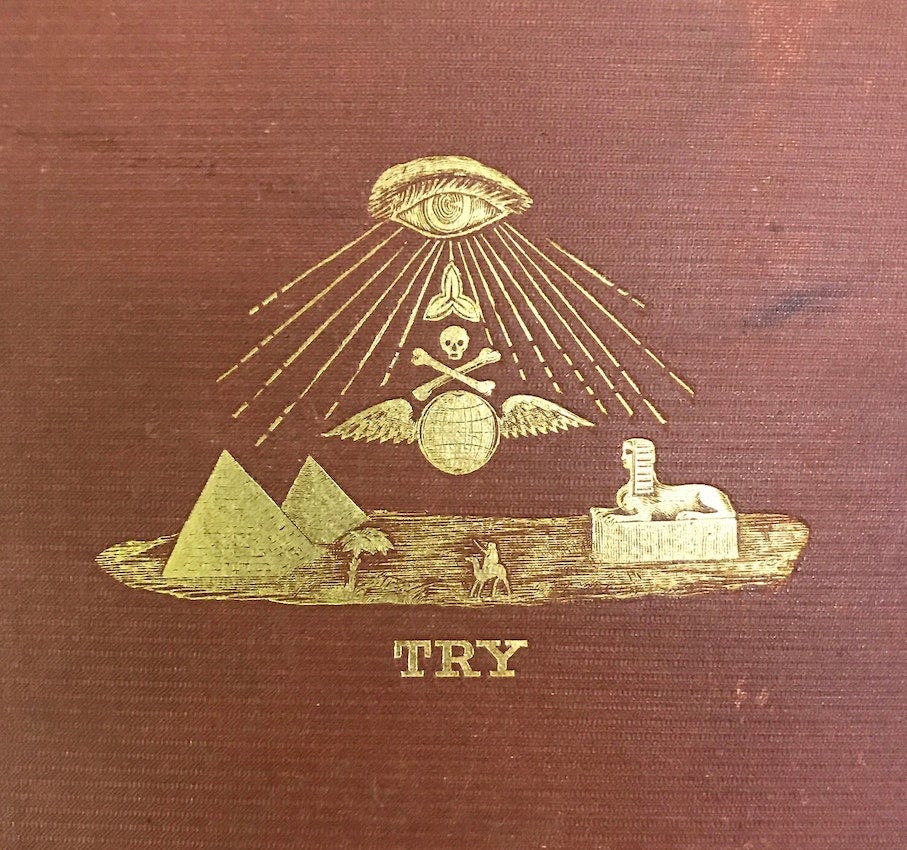

The amazing career and brilliant writing of the 19th Century Black American Rosicrucian sex magician, Paschal Beverly Randolph

Today I thought I would share about someone I find completely fascinating. I discovered Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825 - 1875) while researching my course on the history of the Western hermetic tradition. I am actually quite surprised he isn’t better known and much more discussed. He is a completely unique black American thinker, visionary, and occultist who blazed an extraordinary path through the middle of the long-distant 19th Century.

Randolph grew up in New York City where he was the son of freed slaves, and also claimed Native American heritage. Between the ages of 16 and 20, he traveled the world as a sailor, seeking out mystics and occultists in Europe, Persia, and other ports of call. Back in the US, he performed publicly on stage as a trance medium and became a medical doctor. He promoted sex magic, founded an occult publishing house as well as America’s first Rosicrucian center in San Francisco, wrote a dozen or so books, and taught literacy to emancipated slaves. His death in Toledo, Ohio is shrouded in mystery; he may have been murdered by a jealous student. He certainly packed a lot of action into his half century!

In “The Emancipatory Visions of a Sex Magician,” a perceptive essay on Randolph for The Public Domain Review, Lara Langer Cohen explores the myriad complexities of the magus’ life and work:

Although at times Randolph insisted that “not a drop of continental African, or pure negro blood runs through me”, over the course of his life he increasingly identified with the struggles of Black people. When the Civil War began, he recruited Black troops for the Union army, and during Reconstruction he worked as a teacher and agent for Freedmen’s Bureau schools in Louisiana, participated in important Black and Republican conventions, and served as a correspondent for the Weekly Anglo-African. But from within these established institutions, Randolph was also developing a subterranean praxis that he called “angular and eccentric” and which L. H. Stallings describes as that of a “funky black freak”. He founded a series of secret societies organized around his idiosyncratic interpretation of Rosicrucianism, an esoteric religious movement claiming to preserve the wisdom of a mysterious ancient order, and he dreamed of building still more. Randolph produced a huge body of writing, which he mostly self-published with his first wife, Mary Jane Randolph, and his second wife, Kate Corson Randolph, both gifted spiritual practitioners in their own right. In handbooks, pamphlets, novels, newspaper articles, manifestos, historiography, a wildly embellished memoir, printed “private letters”, handwritten manuscripts, and more, he taught curious students a kind of DIY occult practice that used their own bodies — through study, sex, and drugs — to make connections with the spirit world. But the gospel of a hallucinatory, cosmic sex magic was not an easy path for anyone in the late nineteenth century, much less a Black man. Randolph struggled against racism (which he deeply internalized), economic precarity, and an abiding sense of being an outsider his entire life.

Today, occult thinkers remain marginalized in subcultures. Even Rudolf Steiner — an amazing visionary philosopher — is only taken seriously by a very small esoteric coterie. Today, most would find Steiner’s discussion of cosmic evolutionary cycles, “supersensible" beings influencing humanity, etcetera, nonsensical. Basically we lack criteria to evaluate authors and thinkers who earnestly claim to have direct access to the spiritual worlds via clairvoyance or visionary modes of perception, as both Steiner and Randolph did. Also, a huge gap separates us from these 19th Century occult figures who express themselves in such different cadences, with fantastically ornate rhetorical flourishes. On the other hand, Madame Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley — both very obtuse stylists at best — remain favorites with a wide audience. It doesn’t help that Randolph’s work is largely out of print.

Personally, I find Randolph’s literary style refreshing and immensely charming. He reminds me of Emerson, one of my favorite 19th century writers. There is something in his capacious style and feeling for the range of human experience that conjures up Jack Kerouac, another writer I love. I consider Randolph a forerunner of the Beats, promoting self-liberation, personal gnosis, spiritual sovereignty.

I find myself excited, inspired, transported when I dive into Randolph’s prose. He loved to prolong his sometimes delirious sentences with semi-colons, clauses, and dashes. Here is one characteristic offering, from Disembodied Man, an extraordinary book on the afterlife, where he inquires into the innate sense of a divine presence most of us possess, in some way or other:

Now when we gaze about us, with all our senses in health and active play, and realize how very small we are, how insignificant, in comparison with the enormous vastitude above, beneath, about, and beyond us; if we are really true men; if our souls — our better part—be not subservient to mere sense, mere surface; if we are free, not in the restricted, but the larger sense, — untainted by or with the filth and bitterness of the past; if we shall have bursted our chrysalis shell, and tasted a few drops of the honeyed nectar of the true soul-life, the upper existence, here below, — we cannot help believing that all we see, feel, and know to be around and above us, is, after all, something more than the result of mere accident or fortuitous chance.

Disembodied Man begins with Beverly confessing his own world-weariness (Weltschmerz), yet finding a seam of transcendence that elevates human life above all careworn gloom:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.