The Solar Singularity

Can renewables replace fossil fuels?

What follows is an excerpt from my book How Soon Is Now, published by Watkins Press in 2016. I am less optimistic, today, that we will muster the political will to make the type of systemic changes I defined in that book. While specifics may have changed since How Soon Is Now’s publication, the broad outlines remain the same. Peak Oil, for example, is still a looming reality. (Electronic copies, hard copies, and audiobook available here).

What do you think? Please let me know in the comments.

What Do We Do?

Living in New York City, I see new buildings going up all the time. I don’t see these buildings covered in solar panels feeding energy back to the grid, or vegetable gardens on their rooftops. We keep building needle-thin skyscrapers and luxury hotels, not earth ships and vertical farms.

Young people still pursue careers in the art world, fashion, rock music, celebrity journalism, marketing; they get their degrees in old master paintings and critical theory and so on – I look over their shoulders in East Village cafes to see what they are typing away on. If we prioritized the Earth’s ecology, we would probably apply our intelligence differently at this point. Young people might be encouraged and incentivized to pursue careers in ecosystem management, permaculture, wetland restoration, carbon sequestration. The best and brightest would build systems for sharing and conserving resources, organizing local communities to maximize resilience, and so on, rather than building computer games or working for profit-seeking corporations.

Our system doesn’t reward all of the work that desperately needs to be done now, and it over-rewards everything that shouldn’t be done – such as using marketing to convince people to buy new clothes, cars and gadgets. Those working in financial services make exponentially more than primary school teachers or farmers. And we are all caught in this system.

It is easy to convince one’s self that we have reached the edge of the abyss. But there are many scaleable solutions within our reach. Others will soon become feasible. In a sense, the technical solutions are the easy part, as we will see. The more difficult struggle is to educate people and change our political and economic system so that we can implement the technical solutions rapidly. That requires a leap in collective consciousness, which is not an easy task.

So far, many existing alternatives remain little known. We must act to change this situation as quickly as possible. According to many projections, renewable energy technologies can be exponentially scaled up in a few decades to supply the world’s population with non-polluting energy. If we coordinate a global transition to regenerative, organic and no-till agriculture, we will be able to put a great deal of excess CO2 back in the soil. That transition can also be combined with the rapid distribution of regenerative technologies, like biochar gasifiers and biodigestors that convert organic waste into fuel while sequestering CO2. We can stop all unnecessary forms of industrial manufacturing while we establish networks for sharing and conserving our remaining resources. All of this, in fact, is what we need to do. But how do we do it?

Now let’s consider how we can transform our technical infrastructure if we decide to change our direction as a species, beginning with energy.

Energy

As the residue of millions of years of stored sunlight, fossil fuels were a one-time-only bequest from Earth to humanity. They gave us the opportunity to build a global machine-based civilization, in a few short centuries. Over the last 150 years, we have accessed an enormous quantity of cheap energy. Incredibly, just one gallon of petrol equals 500 hours of human work output. Granted this largesse, it is not surprising we became utterly dependent on cheap fuel.

‘Cheap oil is not a useful part of our economy,’ writes Bill McKibben, ‘It is our economy.’

The availability of cheap energy allowed for the production of inessential goods, impelling the growth of a mass consumer society over the last 200 years. ‘Oil provides 40 per cent of all energy used by human beings on Earth, and it powers nearly all transportation in the industrial world. It’s also the most important raw material for plastics, agricultural and industrial chemicals, lubricants, and asphalt roads,’ writes John Michael Greer. According to Peak Everything author Richard Heinberg: ‘Without petrochemicals, medical science, information technology, modern cityscapes, and countless other aspects of our modern technology-intensive lifestyles would simply not exist. In all, oil represents the essence of modern life.’

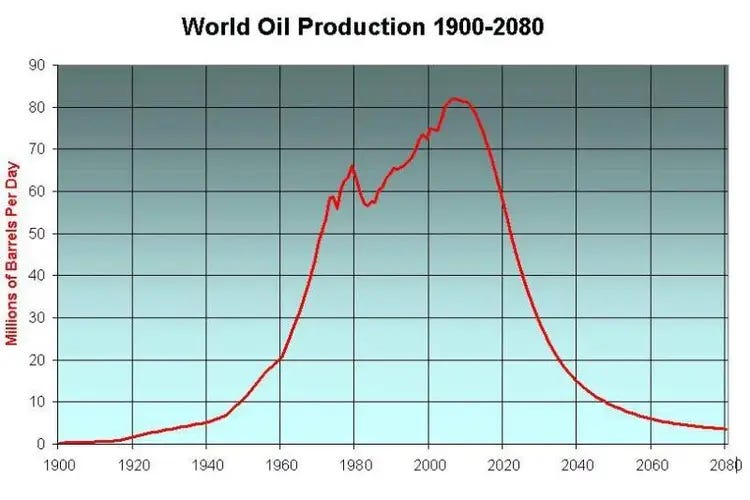

As predicted by the oil company geologist M King Hubbert, we have passed the critical threshold, known as peak oil, when most of the easily available oil has been extracted from the Earth. We have entered a new phase in which fossil fuels become more difficult and expensive to extract, following the downward decline of a bell curve. However, as I write this, the fact that oil has become more costly to extract is not reflected in market pricing – in fact, energy prices keep fluctuating, often going down, and the market is glutted. There are many reasons for this. It is possible that oil-producing countries are keeping prices low to stall the development of renewables. There is also the fact that we are now extracting more fuel from non-traditional sources. But this is not a good thing.

As we run out of traditional sources of fossil fuels, energy corporations pursue, with ever-increasing fervour, procedures such as hydro-fracking for natural gas, mountaintop removal to access coal reserves, and extracting oil from the Alaskan Tar Sands. Their success in developing new processes for accessing these resources has contradicted the predictions of peak oil doomsayers. But this is only a temporary reprieve, and the ecological impacts of these practices are devastating.

The depletion of traditional sources also explains the recent initiative to mass-produce ethanol out of corn. A global rush towards biofuels resulted in global famines, as well as food riots in 37 countries, in 2008. In the future, the depletion of fossil fuel supplies, as well as the limits of our ‘carbon budget’, could make large-scale projects, requiring intensive development of new technology and infrastructure, increasingly difficult to achieve. That is another reason – besides accelerating warming – that we should be seeking to switch to renewables now, when energy is still readily available.

Jeremy Leggett, president of Solar Century, writes, ‘Peak oil is not a theory. Because oil is a finite resource, it is an inevitability. The debate is all about its timing.’ Saudi Arabia, and other oil-producing nations, have passed their peak of production. What follows could be a surprisingly quick decline. Eventually, even unconventional sources of hydrocarbons will run out.

Leggett reports that many experts and insiders ‘think there will be a drop in production within just a few years, and we are in danger of that drop being so steep as to merit description as a collapse’. This collapse would affect not only manufacturing and transportation, but our food system, which requires massive inputs of petroleum to make fertilizer, and for long-distance transport. The average morsel of food in the US travels over 1,500 miles.

In the 1960s, Buckminster Fuller realized we needed to use our resources of fossil fuels to switch to unlimited, renewable sources. ‘The fossil fuel deposits of our Spaceship Earth correspond to our automobile’s storage battery which must be conserved to turn over our main engine’s self-starter,’ he noted. ‘Thereafter, our “main engine”, the life regenerative processes, must operate exclusively on our vast daily energy income from the powers of wind, tide, water, and the direct Sun radiation energy.’ Unfortunately, society went in the opposite direction, burning massive reserves of fossil fuel without establishing a new infrastructure based on renewable energy.

As a side benefit, if we make a global transition to renewable energy sources, we will eliminate air pollution. ‘The idea of a pollution-free environment is difficult for us even to imagine, simply because none of us has ever known an energy economy that was not highly polluting,’ writes Lester Brown, the founder of Worldwatch Institute, in Plan B 4.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization. ‘Working in coal mines will be history. Black lung disease will eventually disappear. So too will “code red” alerts warning of health threats from extreme air pollution.’ As an asthma sufferer, I can appreciate this happy by-product.

We have the technical ability to make this energy transition, but our time for accomplishing it is short. Whatever it takes, we must force our global civilization to put the brakes on its current momentum, and change its course. This requires a realistic reckoning with the urgency of our situation – far beyond the voluntary limits set by the 2105 Paris Climate Conference, also known as the 21st Annual Cooperation of Parties (COP-21), where 195 countries came together but were unable to make the UN Framework on Climate Change legally binding – and a rejection of meaningless half-measures. Let’s take a look at some of the admittedly wonky details.

How Do We Transition?

The likelihood that we can make a rapid energy transition keeps growing due to technical innovations – such as Tesla’s development of the Powerwall, a storage battery for renewable sources usable in private homes, or the ongoing development of the infrastructure for an ‘Internet of Energy’, maximizing efficiency, and allowing people to send extra power back to the grid. Germany is leading the way, particularly with solar. Solar now satisfies around seven percent of Germany’s electricity needs – but on bright summer days this goes up to above 50 percent. While the percentage of world energy needs supplied by solar remains relatively small, the amount has been doubling annually, revealing the potential for a rapid, exponential leap.

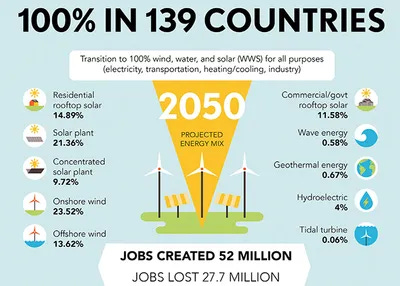

The Solutions Project, founded by Mark Jacobson, Director of the Atmosphere and Energy Program, Stanford University, mapped out a programme for all 50 US states to run on 100 per cent renewable energy by 2050. This envisions a rapid transition in energy infrastructure at the state level, with power coming from numerous renewable sources, including solar, wind, geothermal, hydroelectric and wave devices. To take the state of New York as an example, the Solutions Project proposes that 40 percent of the state’s energy could be generated by offshore wind turbines, with solar photovoltaic plants providing another 35 per cent. The rest would come from a mix of other sources, including solar cells on rooftops.

Similarly, in the UK, a report from the Centre for Alternative Technology at Machynlleth, Zero Carbon Britain: Rethinking the Future (2010), proposes that Britain could completely eliminate fossil fuels in twenty years, through a systemic transition in energy use, production, agriculture and land-use patterns.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.