Below is an excerpt from my book Breaking Open the Head, about modernism and the quest for visionary experience. Starting next Sunday, February 7, I am teaching a four-week seminar, Breaking Open the Head and the Psychedelic Renaissance. As part of the seminar, we will be exploring insights into psychedelics and shamanism from artists and thinkers including Allen Ginsberg, Aldous Huxley, Antonin Artaud, and Walter Benjamin, among many others.

The course will review the history of visionary plant shamanism, the current landscape of psychedelic knowledge and research, and look toward the future of the psychedelic movement as it becomes increasingly integrated into the corporate structures of Capitalism. Together, we will interrogate the current paradigm of psychedelics, which tends to reduce them to therapeutic tools. Is there a deeper potential of the psychedelic renaissance for the future of civilization as well as for us as individuals?

Full course info and link to buy tickets here. Next 10 participants get 1/3rd off the ticket price when they use the promo code, ‘ AreYouExperienced ‘. Paid subscribers to this newsletter get reduced price tickets to this and free entry to other events.

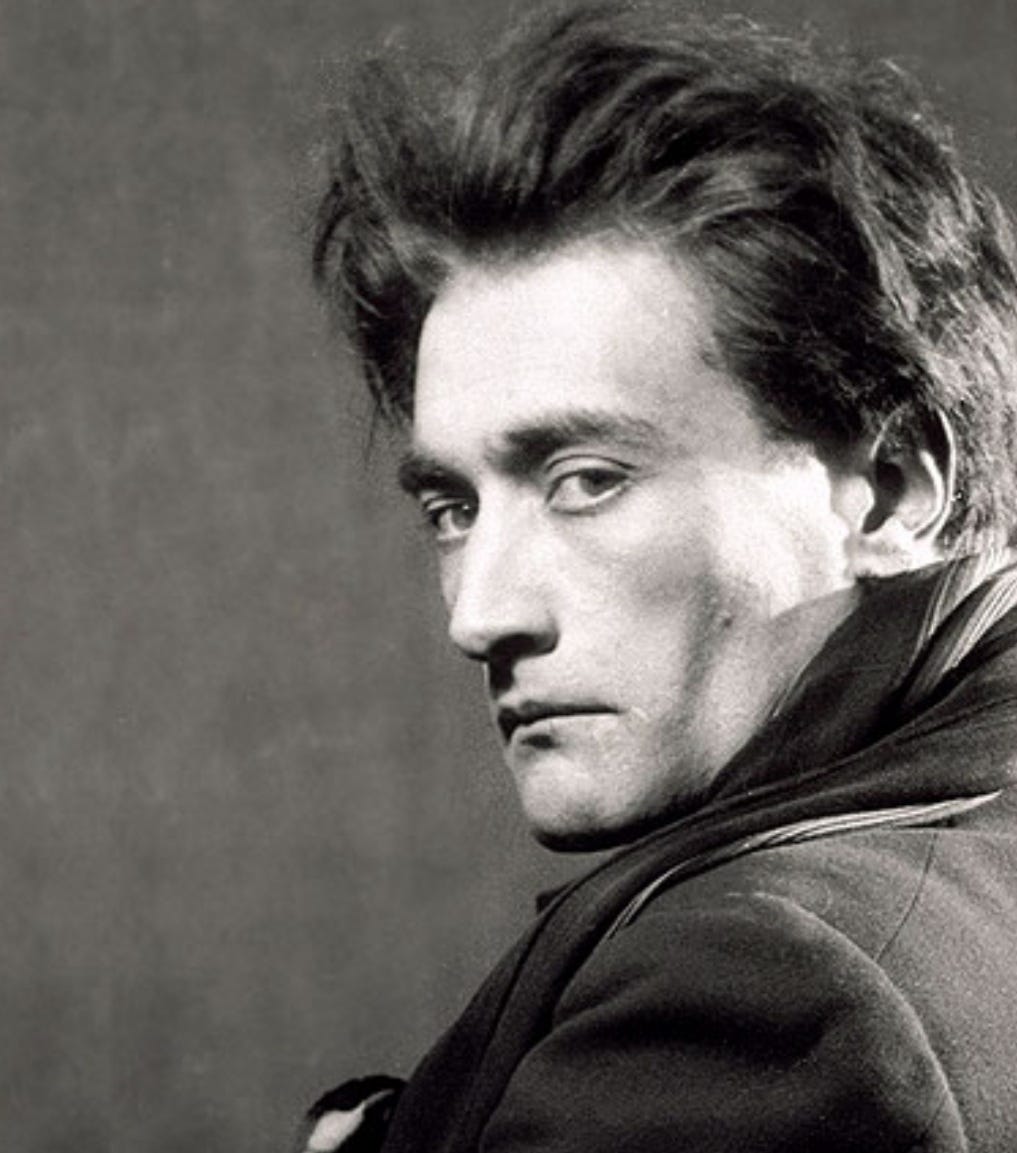

Antonin Artaud

What if the origin of culture, what Carlo Ginzburg called "the matrix of all possible narratives,” was the shamanic journey? Then art and literature, dance and theater would be elaborated or degraded forms of the original impulse to reach the "other worlds" through trance and ritual.

Perhaps modern culture and faith-based religion is a short-term experiment within the larger context of shamanism and its untold millennia of continuity: an experiment in turning away from actual visionary knowledge in favor of cathartic spectacles, symbolic codes, and the mimetic techniques of literature and film; in substituting personal knowledge of sacred realities with faith, and finally, in the secularized West, extinguishing faith entirely in favor of nonbelief in any spiritual dimension of human existence.

The "rediscovery” of shamanism is not just a New Age phenomenon. The Western world has made repeated attempts to understand shamanism, often seeking to reduce it to simple quackery. The process of forgetting and rediscovering, reevaluating and dismissing, shamanism has continued for centuries. From the sixteenth through the eighteenth century, explorers in Siberia and the New World wrote reports of jugglers, conjurers, and tribal sorcerers that were avidly studied by the intelligentsia of Europe. The tone of these accounts ranged from sneering attacks on fraudulent practices and shrill denunciations of devil worshiping, to objective and even compassionate studies of shamanic healing practices.

“While some Europeans continued to ridicule what they considered public trickery and ignoble credulity, others began taking shamanistic practices very seriously,” writes the historian Gloria Flaherty in her book Shamanism and the Eighteenth Century. “Shamanism seemed to them to epitomize a grand confluence of ageless human activities the world over.” Flaherty suggests the evolving cult of the genius, the magic powers of enchantment attributed to Mozart or Goethe, arose out of Europe’s fascination with shamans.

The archetypal figure of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, Goethe amassed information on magic and ghosts, rejected Newton’s mechanistic view of nature, believing that nature was animated by spiritual forces. "We all walk in mysteries,” the poet and scientist wrote to a friend. "We are surrounded by an atmosphere about which we still know nothing at all. We do not know what stirs in it and how it is connected with our intelligence. This much is certain, under particular conditions the antennae of our souls are able to reach out beyond their physical limitations.” Goethe incorporated many aspects of the shaman archetype — contact with ghosts during Walpurgisnacht, drug-induced trance, journeys into the world of the dead, etcetera — into the figure of Faust, the modern magician.

In the nineteenth century, Romantic poets like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Edgar Allan Poe, and Percy Bysshe Shelley obsessively explored their dreams as a bridge between the unconscious and conscious mind. "I should much wish, like the Indian Vishnu, to float about along an infinite ocean cradled in the flower of the Lotos, and wake once in a million years for a few minutes — just to know I was going to sleep a million years more,” wrote Coleridge, whose most famous poem, “Kubla Khan,” was reconstructed from an opium revery.

Like shamans, the Romantic poets were practical technicians who investigated their own dreams and trance states, using drugs among other methods to probe the far reaches of the mind. They trained themselves to produce hypnagogic imagery — the semi-controllable hallucinations that can rise up just at the edge of sleep. Thomas De Quincey, who founded the modern genre of drug testimony with Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, described these visions as "heraldries painted on darkness.” The dream lyricism of the Romantics was an act of resistance to rational empiricism and the Industrial Revolution.

While the Romantics sought to linger in their dreamworlds, the Modernists explored the moment of awakening as the model for a new type of consciousness that could fuse rational and irrational processes. For writers like Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf, the effort made by the sleeper to awake from the dream served as a metaphor for the disconnect between the progressive scientific and social thought of their era, and the primordial, ritualistic slaughter of the First World War. "History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,” announces Stephen Daedalus, near the beginning of Ulysses, a book that includes a one-hundred-page play that takes place in "Night Town,” a transcript of a semi-coherent nightmare or ghost trip that reads like it was dreamt by the book itself.

In Search of Lost Time begins with Marcel Proust's protagonist lying in his bed, sorting himself out from confused and vivid dreams of the past. Proust's opening reveals the moment of waking up as a mystical transgression between the self and the not-self:

. . . when I awoke in the middle of the night, not knowing where I was, I could not even be sure at first who I was; I had only the most rudimentary sense of existence, such as may lurk and flicker in the depths of an animal’s consciousness; I was more destitute than the cave-dweller; but then the memory — not yet of the place where I was, but of various other places where I had lived and might now very possibly be — would come like a rope let down from heaven to draw me up out of the abyss of not-being, from which I never could have escaped by myself: in a flash I would traverse centuries of civilization, and out of a blurred glimpse of oil-lamps, then of shirts with turned-down collars, would gradually piece together the original components of my ego.

Each night, Proust's narrator journeys from psychic dissolution to self-possession, from dismemberment to remembrance. The image of a "rope let down from heaven" is akin to the shamanic motif of a ladder from the sky, leading between this world and the other realms. The vast undersea kingdom of sleep called into question the solidity of the waking reality: “Perhaps the immobility of the things that surround us is forced upon them by our conviction that they are themselves and not anything else, by the immobility of our conception of them.” The sickness that exiled Proust to a cork-lined room, out of contact with other human beings, in a kind of living afterlife, was like the shaman’s initiatory sickness and nervous disorder, his celibacy and his compulsion to separate from his tribe while exploring the spirit realms.

The Modernist writers and artists, consciously or not, borrowed elements from the shamanic archetype. Like tribal shamans, the artists saw themselves, in Ezra Pound’s phrase, as “the antennae of the race.” In a secular culture, they were the ones who journeyed into the land of the dead, who crafted images of an elusive sublime, who went into ecstatic states of inspiration. They believed their icons and testaments, like magic fetishes, contained the power to heal the culture’s spiritual maladies. Writers like Gertrude Stein, Tristan Tzara, or James Joyce explored private languages or languages explicitly made out of nonsense — similar to the shaman’s common practice of glossolalia, speaking in tongues, during trance. The shaman’s songs were taught to him by the spirits; the chants of the Modernist poet were expressions of alienation from a dehumanized and demystified world.

“I Am Not Here”

In the last centuries of capitalism, industrial progress and rationalism were mirrored by a cultural history of frantic visions, symbolic excursions, and narcotic escapes. Artists and intellectuals searched for antidotes to the suffocating materialism of the West. The exploration of chemically induced altered states was one extreme limit, one essential element, of the Modernist quest. The poet Arthur Rimbaud called for "a systematic derangement of the senses," and in the 1920s the Surrealists, following his lead, found inspiration in psychic disorder and extravagant shock effects. Writing on the Surrealists, the critic Walter Benjamin noted: "In the world’s structure, dream loosens individuality like a bad tooth. This loosening of the self by intoxication is, at the same time, precisely the fruitful, living experience that allowed these people to step outside the domain of intoxication.” Altered states allowed thinkers to escape, temporarily, from the overwhelming, and intoxicating, dreamworld of capitalism.

Modernist artists pursued the deviant and disgraced, sought out what had been refused, tossed aside, made alien by the West. The resurgence of interest in the sacred tribal medicines, which began with a few dedicated and often desperate seekers, opened a new phase of the Modernist exploration of cultural otherness: an attempt to make direct contact with the visionary knowledge of "primitive" societies.

The writers of the twentieth century who first took the psychedelic voyage out — Antonin Artaud, Henri Michaux, Aldous Huxley, and William Burroughs among them — found that the tribal sacraments, off-limits and little known in the West for many centuries, had a split identity. On the one hand, the substances opened vast domains of perceptual awareness, sparked new ideas, and unleashed visions that seemed to unfold from the Jungian collective unconscious, or from the mind of a supernatural trickster. But the experience was also one of abjection and anxiety and helplessness.

Artaud traveled to Mexico in 1936 to take part in the peyote rituals of the Tarahumara Indians, a remote mountain tribe living on barren peaks a few days' journey from Mexico City. The tormented poet went to the mountains of the Tarahumara out of desperation. He yearned to recover "that sense of the sacred which European consciousness has lost . . . the root of all our misfortunes.”

Artaud suffered internal exile from his own mind, his own thoughts, “a fundamental flaw in my psyche.” In his writings, he returned, over and over, to this inner separation, felt as terror, as rupture, as yearning for connection to some reality. "I am not here,” he wrote to a friend. "I am not here, and I never will be.”

Poet, actor, founder of the Theater of Cruelty, inspiration for generations of embarrassing pseudotransgressive spectacles performed in liberal arts colleges and fringe theaters around the world, he has a deserved reputation as a radical and histrionic figure who once declared, “All literature is pigshit.” Some of Artaud’s writing is mad ravings and some is extremely tough going, but he was also capable of great lucidity. Seeking clues to his condition, he probed among mystical traditions, alchemical processes, the fragmentary shards gleaned from his own inner world: “There is a secret determinism based on the higher laws of the world; but in an age of a mechanized science lost among the microscopes, to speak of the higher laws of the world is to arouse the derision of a world in which life has become a museum.” His life was a quest for those higher laws.

For a time, Artaud belonged to the doctrinaire Surrealist party: "Surrealism has never meant anything to me but a new kind of magic. The beyond, the invisible, replaces reality. The world no longer holds.” Surrealism was, for Artaud, a system of techniques for exploring irrational, mystical, and dissociative states — those domains of consciousness that a materialist culture discards as useless. Surrealism showed how, “Out of the right use of dreams could be born a new way of guiding one’s thought, a new way of relating to appearances.”

He split the Surrealists when they turned to communism. For Artaud, the fact that the Surrealists joined the communists only proved that their revolutionary impulse had not penetrated deeply enough. “The revolutionary forces of any movement are those capable of shifting the present foundation of things, of changing the angle of reality.” Communism was doomed to failure because it didn’t recognize, didn’t transform, "the internal world of thought.”

To reach the Tarahumara, Artaud passed through a primordial landscape inscribed with symbols, numbers, and images — blasted trees like crucified men, demonic faces peeking from rocks. Later he saw the shamans of the Tarahumara weave these symbols into a living cosmology that expressed the essence of their mystical science. "This dark reassimilation is contained within Ciguri (peyote), as a Myth of reawakening, then of destruction, and finally of resolution in the sieve of supreme surrender, as their priests are incessantly shouting and affirming in their Dance of All of the Night.” Like the Bwiti, the Tarahumara had a symbiosis with their magical root. When the shamans danced, Artaud realized, "they do what the plant tells them to do; they repeat it like a kind of lesson which their muscles obey.”

European Modernists like Pablo Picasso and Andre Derain were fascinated by “Primitivism.” Cubists, Fauves, and Futurists took their formal innovations from African masks and Eskimo totems. Despite this interest in the exotic and tribal, only Artaud, of all the European Modernist artists, had enough desperation or courage — often they are the same thing — to venture into the tribal reality and eat the visionary sacrament for himself. Only for Artaud was achieving this knowledge a matter of life or death — or even beyond. He was not looking for any other reward: “I had not conquered by force of spirit this invincible organic hostility ... in order to bring back from it a collection of moth-eaten imagery, from which this Age, thus far faithful to a whole system, would at the very most get a few new ideas for posters and models for its fashion designers.” Thirty years ahead of his time, Artaud presciently conjured the late 1960s, when psychedelia turned mass market, producing much "motheaten imagery” for the machinery of advertising, TV and design.

The Peyote Dance, Artaud's text on his voyage, worked and re-worked over many years, while its author suffered in mental hospitals, is a fractured narrative made up of stops and starts, convulsive revelations and tormented cries. A unique mytho-poetic masterpiece, his text is shot through with Christian images of crucifixion and redemption, the pressure of his madness, his yearning to reenchant the world. "For there is in consciousness a Magic with which one can go beyond things. And Peyote tells us where this Magic is, and after what strange concretions, whose breath is atavistically compressed and obstructed, the Fantastic can emerge and can once again scatter in our consciousness its phosphorescence and its haze.”

The Tarahumara, far from being savage or backwards in their beliefs, were actively seeking answers to the deepest questions of philosophy. "Incredible as it may seem, the Tarahumara Indians live as if they were already dead. They do not see reality and they draw magical powers from the contempt they have for civilization.” The Indians pursued metaphysical knowledge in a direct, visceral way, through dance, ritual, and, above all, through Peyote. "The whole life of the Tarahumara revolves around the erotic Peyote root.”

The Tarahumara shamans fooled with Artaud at first, as shamans like to do. "They thrust on me these old men that would suddenly get the bends and jiggle their amulets in a queer way,” the poet complained. "I saw they were palming off jugglers — not sorcerers — on me.” At first the Indians did not want him to participate in the ciguri rituals: "Peyote, I knew, was not made for whites. It was necessary at all costs to prevent me from obtaining a cure by this rite which was created to act on the very nature of the spirits. And a White, for these Red men, is one whom the spirits have abandoned.”

But Artaud was tenacious. He waited them out. He also learned that the Mexican government was trying to stop the peyote rituals; he confronted the local schoolmaster about it. Later he learned the Tarahumara knew their tradition was coming to an end. The spirit was abandoning them — and all men. "Time has grown too old for man," a priest told him.

He made friends with a tribesman who explained, at least in Artaud’s recollection: "Peyote revives throughout the nervous system the memory of certain supreme truths by means of which human consciousness does not lose but on the contrary regains its perception of the Infinite."

Eventually the real shamans arrived. He was allowed to join their all-night peyote ceremony. He was the first white man, the first Western intellectual, to do so. He ate a fistful of the powdered root, received those “dangerous disassociations it seems Peyote provokes, and which 1 had for twenty years sought by other means.” He watched primordial symbols rise from his inner organs: "The things that emerged from my spleen or my liver were shaped like the letters of a very ancient and mysterious alphabet chewed by an enormous mouth, but terrifying, obscure, proud, illegible, jealous of its invisibility.” He witnessed the fiery letters J and E burning at the bottom of a void — an immense void that was somehow contained within his own body.

"Peyote leads the self back to its true sources,” he wrote. “Once one has experienced a visionary state of this kind, one can no longer confuse the lie with the truth. One has seen where one comes from and who one is, and one no longer doubts what one is. There is no emotion or external influence that can divert one from this reality."

As powerful as they were, these revelations could not cure his inner divisions. They could not heal him. Artaud spent the last twelve years of his life in mental institutions, treated by electroshock, writing paranoid letters and increasingly incoherent rants, and revising the text of his revelations among the Tarahumara. Like some of the psychedelic martyrs of the 1960s, Artaud’s quest for shamanic knowledge ended in self-destruction. But what other fate was possible or even conceivable for the modern Western artist, compelled beyond any worldly ambition to cross the spiritual wasteland, to resacralize himself and his culture?