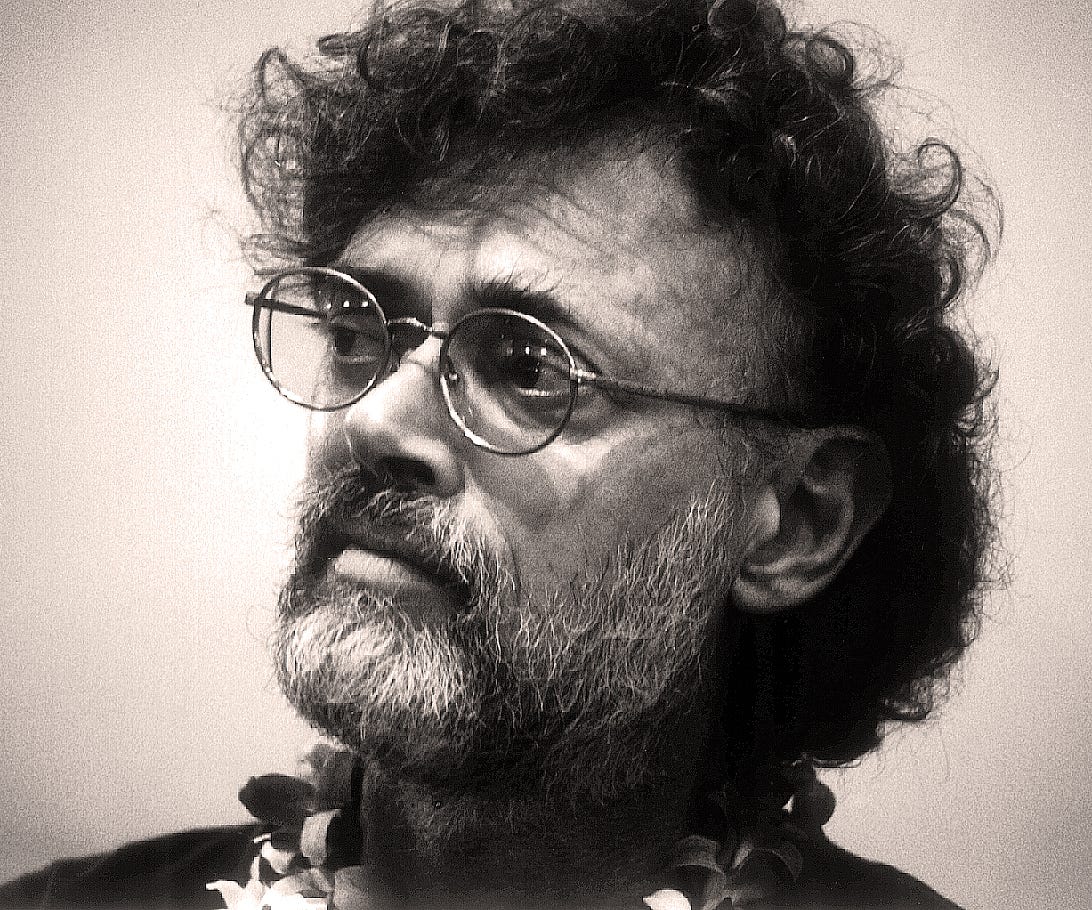

For the last few days I have been reviewing this extraordinarily prescient interview with Terence McKenna from twenty-five years ago (October, 1998). McKenna was a huge influence on my books and my thinking but I haven’t engaged with him in a while. His ideas remain fantastically relevant, fresh, inspiring, fascinating. I feel we must keep remembering them as we slide-slither further toward the Eschaton (the end of the end… if that’s indeed where we are heading).

Today we live in a world over-saturated with noise, news, factoids, endless interpretations, incessant events — it is overwhelming and inundating. I admit I struggle with the feeling that I don’t want to contribute to it anymore. I’ve been waiting for something new to rise up within me, some sense of deeper pattern or coherence. A truth that is worth sharing. Sometimes you have to wait a bit, in darkness and silence, for something to emerge.

McKenna anticipated our contemporary chaos — the palpable sense we have now of breakdown, rupture, and telescoped collapse. With his novelty theory, he proposed that the universe innately, purposefully, seeks out complexity and innovation. The speed of the universe’s quest for novelty keeps accelerating, to the point where we may, eventually, experience thousands or millions of years of evolutionary time in a few short moments:

Novelty increases as we approach the present moment. The universe you and I are living in is a far more novel and complicated place than the early universe was. Some people would say, ‘Well, that's just a consequence of the unfolding of developmental processes.’ But this begs the question: What are developmental processes? Why should the universe have a preference for order over disorder, especially when we have something called the second law of Thermodynamics which tells us exactly the opposite? Physicists believe the universe is running down, ultimately, into a state of disorder. But what I see is, everywhere, the emergence of more and more complex forms — languages, organisms, technologies — always building on the previously achieved levels of complexity.

McKenna noted that novelty was not necessarily benevolent or kind. Novelty increases complexity, which means, as we approach the Eschaton, a “zero point” of accelerating transformation and exponential change. He predicted the world would get increasingly bizarre and demented, which is indeed the case:

I think it's just going to get weirder and weirder and weirder and finally it's going to be so weird that people are going to have to talk about how weird it is. At that point novelty theory can come out of the woods, because eventually people are going to say, “What the hell is going on? It's just too nuts.”…

I look for the invention of artificial life, the cloning of human beings, possible contact with extraterrestrials, possible human immortality, and, at the same time, appalling acts of brutality, genocide, race-baiting, homophobia, famine, starvation, because the systems which are in place to keep the world sane are utterly inadequate to the forces that have been unleashed.

We see this escalating weirdness in our current political turmoil. In the US, we have an octagenerian President who can barely speak — a final vestige of the Baby Boomers, still clinging to power — yet he is all that stands between us and a resurgent Fascism, now backed by the super-wealthy elite of Silicon Valley. Trump continues to have an occult field of protection around him that protects him from harm. Ears are notoriously close to the skull. Trump gets grazed by a bullet, bleeds flamboyantly from a tiny wound on the outside of his ear, and is barely hurt. This is astronomically improbable. Our situation is mythological: We wouldn’t believe it if we saw it in a film.

McKenna, who died of brain cancer in 2000 at the age of fifty-four, was a proponent of the idea that December, 2012, would be the Eschaton, the threshold of “concrescence” or “Singularity,” based on his Time Wave Zero predictions, which meshed with the Mayan long count calendar. However, he also admitted he might be off by ten, fifty, or five hundred years, and this would make no difference whatsoever. These are infinitesimal timespans in relation to the four billion plus years of the evolution of life leading to this point.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.