What Happened to Art?

Seeking the cutting-edge of creative expression today

I am delighted to announce that we have just launched a new platform for online seminars: www.theliminalinstitute.com . Please check it out. We have lowered the prices for recent seminars including my 4 classes on Breaking Open the Head and one-time workshops on Rudolf Steiner and ETS / UFOs. Also, anyone who becomes a paid subscriber of the newsletter now will receive access the Breaking Open the Head seminar for $25 and Building Our Regenerative Future (over 24 hours of tremendous content) for just $50. I hope you will join us!

Does anyone else share the eerie feeling that new artworks, films, and literature no longer function, don’t hold the same power, as they once did? It seems that what we once knew as cutting-edge culture has lost much of its influence on society, its capacity to change collective consciousness. These days, it is difficult to find a new cultural imprint that seems significant — to separate out the new signal from a deluge of noise. People I know rarely discuss a new film, exhibition, or book with the breathless excitement that comes from making a new discovery, as they did in the past.

For reasons I will explore, I am not sure whether this is entirely a bad thing. I also don’t know to what extent the feeling I have is due to my own history. After all I have been immersed in artistic expressions for a number of decades now. Perhaps this has brought me to a point where I find a certain predictability, repetitive patterns, in most artistic efforts.

When I was young, I found novelty, amazement, solace, and shocks of recognition when I read great literature or went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to visit the Van Goghs, Rembrandts, Pollocks, the African and Polynesian collections, and so on. Modernist culture, in particular, filled a deep yearning for me – authors like Virginia Woolf, Kafka, Henry Miller, Proust, Rilke, Thomas Bernhard, Julio Cortazar, among many others. Along with certain music and film (Godard, Fellini, Antonioni), such works shaped my attitudes and ideas about the world, in many ways. They were tools that transformed my consciousness.

In my twenties, I wanted to be a poet and novelist. I co-edited a literary magazine, Open City. We hope to help create and be part of a literary and artistic movement, a scene, like ones from the past. As a journalist, I wrote about art, interviewing artists for magazines like Art in America and The Art Newspaper of London.

My parents were both artists who shared a passionate faith in the value of personal expression. I never really considered being anything other than an artist of some sort. My father moved to New York from Brighton, England, to join the Abstract Expressionist movement, but arrived a half-generation too late. My mother was connected to the Beat Generation as a young woman. Later she wrote a memoir, Minor Characters, about her relationship with Jack Kerouac and the Beats.

The Mudd Club, 1980

When I was in junior high school, my father discovered the New Wave and Punk movement which flourished in New York in the late 1970s. He took me to places like the Mudd Club and CBGBs, dank clubs vibrating with electric possibilities where generational consciousness – edgy, raw, amorphously outraged – was in the process of discovering itself.

Many things have happened over the last few decades to change the collective consciousness. One of these is, of course, social media. Our incessant immersion in the digital and virtual costs us a certain degree of interiority and unique subjectivity. With our ever-present phones, we can’t escape the intrusion of the collective into our inner space of self-reflection. This insistent presence is like an implicit, mute Greek chorus, ever ready to judge, praise, condone, or condemn.

Our ubiquitous phones and laptops also represent the deeper incursion or penetration of Capitalist economics and the one-dimensional logic of the market into our interior psychic realm. Every Tweet, blog or photo we post enters immediately into the liquid medium of society as a whole. People shape their ideas and creative content according to how it will be instantly received, whether their audience is a few hundred or many millions. Lewis Mumford once noted that Capitalism makes us wake up every morning, look in the mirror, and ask ourselves, ‘What part of my personality can I sell today?’ Social media is, today, like a mirror that looks back at us.

Because I grew up in the pre-Internet age (I remember I was commissioned to write a proposal for a book on the future of the “information super highway” back in the early 90s, before anyone knew what it would turn into), I am still surprised when I discover how platforms like Instagram have colonized the psyche of younger people. They experience it as a powerful reality, equal to or more important than their visceral interactions in the world. Shaped by a different time, I have never taken it so seriously.

For many people I know — particularly those in creative fields — their digital persona and social media reach have a direct link to their economic value, their capacity to generate revenue. Over time, this tends to erode any distinction between public and private spheres. It would be instructive to compile a list of all the ways that social media has impacted our contemporary sense of self. Hypnotic and hyper-addictive, it reduces our capacity for sustained reflection and spontaneous response.

Instagram culture has perhaps reached its apex in the last years. One beach hotel in Tulum is famous for its biomorphic design as well as notorious for its unfriendliness and disregard of the local ecosystem. People will pay up to $8,000 a night in high season to stay in intentionally rustic rooms with no air conditioning. They buy expensive drinks at a bar where security guards block anyone from stepping outside of narrowly defined sectors. I struggled to understand what the appeal of this was, until someone explained to me that it was all about Instagram. Guests subject themselves to this misery in order to capture Selfies of their perfect lifestyle, presumably showing off to all those who don’t make the grade.

The constant presence of the invisible social as ghost realm or Greek chorus, ever ready to judge or applaud or condemn us through our phones and laptops, degrades consciousness, reduces interiority, curtails individuality. We live in a shallow culture where everything must make its point immediately, with no mystery or ambiguity, no depth of curiosity or openness. The only antidote to this is our individual choice to reject the linear logic of the market and the narcotic narcissism induced by social media, reclaiming the depth dimensions of interior reflection for ourselves.

While the hypnotic power of social media and the digital sphere is one reason that art has lost some of its influence and impact, it is not the only cause. In 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl, I explored ideas of the philosopher Jean Gebser who thought we are in a transition between two “structures of consciousness.” This is more than a shift in world views. When humanity reaches a new structure of consciousness, we enter into a new reality that has different possibilities inherent within it.

Gebser wrote about these structures of consciousness as different ways of understanding and living in time as well as space. These structures – Gebser enumerated several past ones, the archaic or aboriginal, the magical or tribal, the mythical or cyclical; our current one, the mental-rational; and our future one, the integral or aperspectival – also transform humanity’s self-awareness and change our individual consciousness. Each structure also has forms of artistic expression and ritual that mesh with it.

The Absinthe Drinker (1875) by Edgar Manet

Over the past centuries, modernist and postmodern art reflected the consciousness of industrial civilization — defined by reductive scientific materialism that left no place for spirit or soul — as humanity went through rapid changes. A great deal of 19th Century Impressionist painting, for instance, focused on the new leisure activities, boating and such like, enjoyed by the bourgeois and working class in a world defined by the mechanical time of the clock, which separated work from leisure in a new way. Such antiheroic and non-mythic themes would never have been deemed worthy for art, for monumental paintings, in the Renaissance or Middle Ages.

The discovery of perspective in the Renaissance profoundly changed art as well as human subjectivity. For the first time we fully entered the spatial realm. In a sense, Gebser wrote, we became “possessed" by space and matter. We saw everything for the next centuries after that in terms of space and matter. This included “intensities" that could not really be defined as spatial or material, such as time and consciousness. We still think of time as akin to a material quantity. We talk about “wasting time” or “spending time” or “running out of time”. This is a distorted perception, as time is not comparable to space.

Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2 (1912) by Marcel Duchamp

For Gebser, early Twentieth Century art movements like Cubism, DaDaism and Futurism were efforts to address the flawed conception of time as equivalent to space – time as an unvarying linear extension — which had been held since the Renaissance. The paintings of Cubism that showed many angles of a figure at once, or a work like Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, revealed the “irruption" of time into consciousness, but in a still quite primitive form. These art movements happened while physics made a series of mind-bending breakthroughs.

Physicists discovered that time was relative, that conscious observation caused a probability wave to collapse to a definable particle, and so on. The physicists’ findings led them to propose that space-time already existed in its totality from the perspective of a higher dimension, and that the physical universe was more like a “great thought” than a set of tangible things. These insights more closely resembled Eastern mysticism and ancient metaphysics than the prevailing Newtonian-Cartesian paradigm. They remain difficult for our society to integrate, even today.

Still from L’Avventura (1960), directed by Michelangelo Antonioni

Modernist art expressed a sense of rebellion, freedom from the dead weight of the religious past, but also a sense of horror at the empty, void-like state of a universe without any sacred or divine dimension to it. Think of Kafka with his parables of immutable judgment or Samuel Beckett’s existential despair, or the lost, dispossessed heroes of Antonioni’s films. The ultimate discovery of DaDaism and neo-Dada artists like Koons or Warhol is that any object, no matter how tacky or mass-produced, once isolated and presented in the pristine container of a museum or gallery, takes on a numinous quality. A urinal, vacuum cleaner, or Campbell Soup can will stand in for the religious relic or sacred totem — as an ironic reminder.

We can think of culture as the learning from other people's learning. Each generation assimilates some of the knowledge painfully accrued by past generations almost automatically, without thinking much about it. The content and style of modernism and postmodernism are easily comprehended, at least vaguely, by the young , even if they receive it in a commercial, stereotyped way. Lady Gaga, to take just one example, borrowed from difficult, high brow performance art, taking from it what she could sell to the masses.

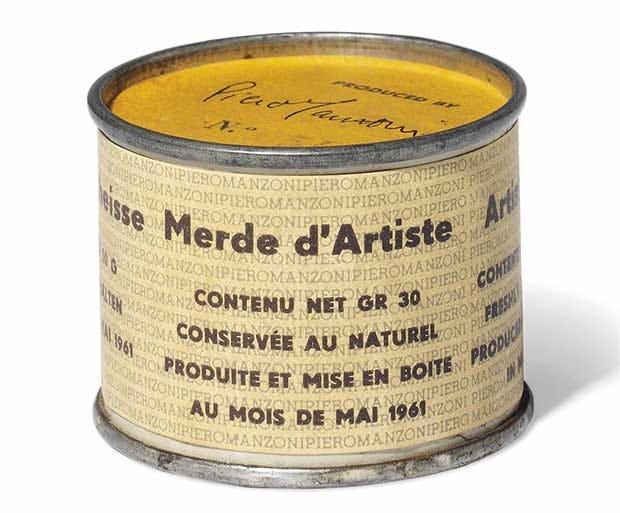

One thing that seems definitely worn out, over and done, is the capacity of new art to gain attention and accrue value from being more transgressive or more shocking. All of the possible transgressive tricks and tactics have been used already. Artists have canned their shit, stacked the cans in galleries, and sold it. They have documented heroin addiction and every form of depravity and degradation. They have been shot or crucified to the roof of a car. They have hung themselves on the wall and invited the audience to torture them. Etc. Anything else along these lines would just be Baroque elaborations on a theme.

In The Rebel, Albert Camus proposed that only two worlds ultimately exist for the human mind: The world of rebellion or the world of the Sacred. These are the two opposite poles which the human mind swings between. I think this is true.

We have exhausted the world of rebellion over the last centuries. We rebelled against nature, order, God, the feminine, etcetera. We must, therefore, be scrabbling to find our way back toward a sacred vision of the world, somehow or other. It is the only way that art can find its proper role and function again – and of course, art can also help to illuminate the path we traverse in between.

I admit I find it embarrassing to write in lofty terms about the “sacred” or the “spiritual.” I am someone who has made many mistakes in my life and continue to make them. I am not a devout meditator. I rarely pray. I feel more connected to the edgy, avowedly Left Wing, bohemian counterculture of my parent’s generation, with its commitment to spontaneous self expression, than I do to the post New Age spiritual culture of yoga and neo-shamanism, which in Tulum is very much the status quo and has a slightly glossy feeling to it that I find constricting. It avoids shadow and ambiguity.

Having said that, I will also say that the “consciousness culture” here in Tulum, as at Burning Man and other transformational festivals, shows us what is emerging. As we leave behind the old culture of modernist and postmodernist rebellion, which was focused on the de-centering and deconstruction of meaning as well as the subject, we can turn our attention to the exploration of consciousness and subjectivity, in itself.

We see nascent efforts to build from the ruins. And this can only be applauded, even when this no longer quite-so-new neo-spiritual culture utilizes pastiche — a trope of postmodernism — to mash up the world’s esoteric traditions. This culture can also be accused of extending the logic of Neocolonialism. Now that the dominant Western culture has stripped everything from the indigenous people, taking their forests and lands and cultures, we are now absorbing their spiritual practices as well, assimilating them, because, we now realize, they benefit us.

The inability of new art to impact us as it did previously has something to do with this deeper shift happening within society, within consciousness itself, as we leave behind the Modern and Postmodern rebellions. The inner drama of a tormented individual subjectivity undergoing existential throes and absurdist confrontations with the void is no longer so enticing. We desire something more — something new — even if we don’t know exactly what it is, as of yet.

We can rest assured that it is nothing we will find on Netflix. Over the last decade or so, Netflix assumed a position of cultural power. It pivoted its business model from loaning DVDs of films to making it’s own content. This includes wildly popular series such as Black Mirror and Stranger Things. The content that Netflix produces often has a dark, dystopian quality. It applies many Modernist and Postmodern tropes.

I was fascinated to learn that Mark Randolph, the co-founder and first CEO of Netflix, is the grand nephew of Edgar Bernays, the founder of modern public relations, who was himself a grand nephew of Sigmund Freud. Bernays is widely recognized (he was the focus of the Adam Curtis documentary, The Century of the Self) for applying Freudian psychology to PR. For instance, he was hired by a cigarette company in the 1920s to get women to smoke more. Bernays came up with the idea of holding flapper parades that ended with a horde of glamorous women lighting what they called “torches of freedom,” but were in fact cigarettes. By associating smoking with female liberation, Bernays helped increase sales of these fatal products.

Bernays coined the term “engineering consent.” He argued in his book that the elites needed to consciously manipulate the masses to maintain their control over society. When I found the link between Bernays and Randolph, it crystallized my sense that Netflix is expertly designed to manipulate the mass Psyche. The malevolent mood of so much of Netflix’s content meshes with the dark ambiance of our society. It prepares people for future technocratic outcomes – for instance. the interminable lockdowns, enforced experimental vaccines, and other aspects of the Coronavirus pandemic we are experiencing now. Our media has primed us for dystopian scenarios for decades. These now seem to be coming to pass, as advertised and foreordained.

There is some good content to be found on Netflix, but most of it is awful. You never find more than a few thoughtful movies on the network, despite their vast catalogue. Netflix seems frustrating, almost by intention. Their content reflects intensive market research into the generic, algorithmic desires of the masses. I find it depressing that Netflix shows have become acceptable substitutes for truly challenging or thought-provoking content. Of course, Netflix shows — along with the rest of the canned content produced by similar networks — never challenge the Capitalist system of exploitation itself, which is rapidly dismantling the planet. Instead, they tend to present increasing technological control as a forgone conclusion.

And that may be another reason that art has stopped feeding our souls as it used to, why it no longer seems to satiate our hunger for meaning and purpose as it once did: We all know we are in an emergency. The Earth’s ecosystems are breaking down under the assault of industrial civilization. We are seeing gigantic annual forest fires, disappearance of insects, dying coral reefs. The Amazon jungle may collapse as a functional system within 15 years. And so on.

Artists should be ringing the alarm bell. They should be helping people envision radical movements and post-capitalist alternatives rising from the ashes. But few are doing this. Instead, many of them have gotten caught in digital distractions, such as seeking to monetize their work via NFTs.

We lack for cutting-edge artists with fresh insights into this strange, dangerous time. Crisis should provide an opportunity for artists and writers to step forward, to take leadership roles, to write manifestos and make clarion calls for positive change. But few artists today have the courage or scope to do this.

Collective belief and social trust has shifted toward a false icon: The tech billionaire as savior. In our secular culture, belief in the future of technology has become a kind of religion. The idea that we are approaching “The Singularity” provides an eschatological framing for secular culture. Soon humanity will merge with our machines. This sidea cannot even be questioned. In fact it must be accelerated: The machine has become God.

This is one reason some of us want to avoid Covid vaccinations. We are being asked to cede control of our bodies to technocratic governments and opaque institutions. We are giving them a mandate to inject us whenever emergency is declared — and emergency may be the new permanent state of affairs. Nobody can predict the unforeseen consequences of these vaccines, which remain experimental. This leaves the dissenters with two choices: to rebel against this technocratic control system as best we can, or acquiesce to being part of a vast, uncontrolled biological experiment.

It may be that the traditional environments for artistic expression – the book on the shelf, the art in the gallery, the theatrical movie – are no longer places where creative breakthroughs can happen. I had this insight many years ago when I went to Burning Man for the first time: Perhaps the future of cultural expression does not reside in individual art works but in “social sculptures,” a term coined by Joseph Beuys. Some artist or collective can define a set of principles or “game rules,” like Burning Man’s ten principles. The rules allow everyone to join, play and create, in a new social environment.

I am feeling a second wave of hope that something transformational may emerge from the blockchain. With blockchains, engineers can design new systems for cooperation, decision-making and value exchange. Such experiments may open new social, political, and ecological possibilities for experiment, participation, rebellion, and ecological activism. We may find the next threshold of artistic expression — the thing we are waiting for, in other words — not in traditional art-making but in the launch of new “social sculptures” that orchestrate human interactions, support Temporary (or even Permanent) Autonomous Zones, and so on. These orchestrations could be unleashed via new tokenized structures, built on blockchains.

I hope that our society turns back toward complexity, ambiguity and deeper self reflection. I hope young people still find, through art, shocks of recognition, tools of transformation. That they explore beautiful wormholes of incandescent strangeness, plunging into an interior universe emanated from another psyche, whether made of words, brushstrokes or software code. Art has the power to reveal new domains of human possibility. There are infinite imaginal worlds awaiting some courageous soul to discover and define. That will remain true even if the art of the future takes unknown and unexpected forms.

.

hi Daniel! thanks so much for all the great observations in this (brilliant) analysis - only one thing really stuck out for me in it that seemed worth questioning; IMO, hoping for Blockchain- related tech to be anything but environmentally catastrophic anytime soon (unfortunately) seems misplaced; with the comment in mind you made about NFT's themselves being "digital distractions" also consider this from a few weeks ago; "the Guardian estimated that the sale of 303 editions of Earth, an NFT produced by the musician and artist Grimes earlier this month, “used the same electrical power as the average EU resident would in 33 years, and produced 70 tons of CO2 emissions.” ..+ from what I gather even the most optimistic scenarios for BC's eco-sustainability seem a long way off...+ it seems evident that the whole phenom itself was (unsurprisingly) initially, voraciously developed, like so many things in tech, without any real long (or short!) term regard for the environmental impact/ consequences...+ my assumption here would be that, you being you, that you probably already knew all this, etc...which then leads me to wonder what your thinking/ rationale would be for still advocating for it the way you do...especially as a sort of "glimmer of hope" at the end of the essay? (+ IMO this hope seems additionally curious as earlier in the essay you explicitly lamented the "...the deeper incursion or penetration of Capitalist economics and the one-dimensional logic of the market.." which in all likelihood, would/ will continue to be the primary material and idoelogical modalities this tech is used within?) thanks man

"Our incessant immersion in the digital and virtual costs us a certain degree of interiority and unique subjectivity. With our ever-present phones, we can’t escape the intrusion of the collective into our inner space of self-reflection. This insistent presence is like an implicit, mute Greek chorus, ever ready to judge, praise, condone, or condemn." I could not agree more. Your comments on modern film and television are also spot on.