Egregores

Autonomous psychic entities energized by human thought

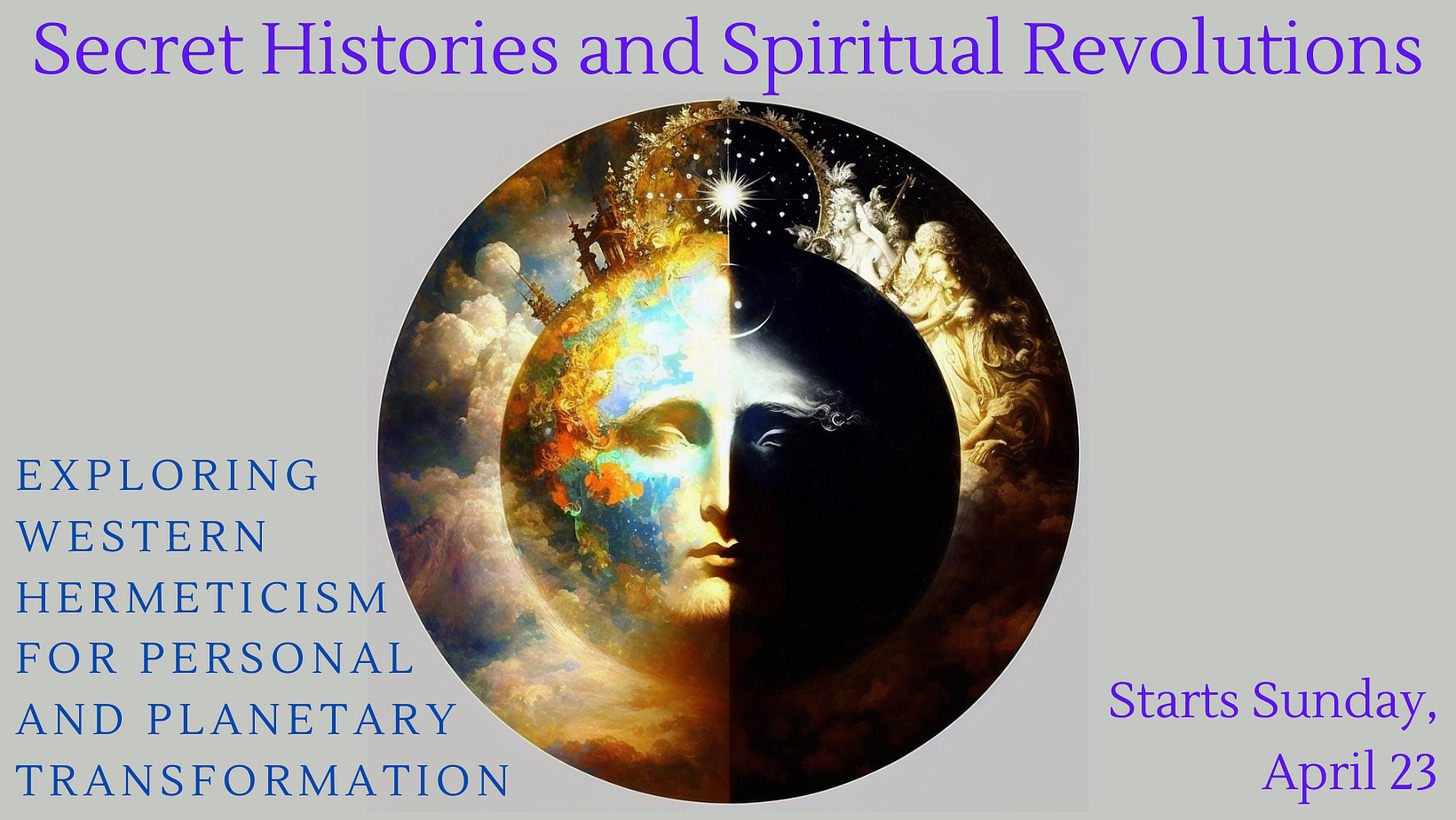

Secret Histories and Spiritual Revolutions starts Sunday, April 23rd, at 1 pm EST (9 am PST, 6 pm CET). Each session will be three hours long, starting with a presentation followed by a discussion.

Sessions will be live on Zoom, with recordings available the next day. There will also be suggested readings and optional visualization / meditation / ritual exercises. Certificate of completion available.

The course is $249.99. Today you can sign up for an Early Bird Special at 40% off ($149.99). For paid subscribers to this newsletter, the Early Bird price is $100.00 until Monday. I sent out a separate email to paid subscribers with the code. I offer lower-priced and scholarship tickets for those in need.

In this essay, I will continue to explore my personal and philosophical context for Secret Traditions and Spiritual Revolutions, my upcoming seminar on the Western hermetic tradition. I suspect we have entered what the ancient Greeks called kairos, an opportunity for a total transformation of worldview and values. To bring about this transformation in a positive sense, we must reconnect with the esoteric and occult streams, flowing beneath the surface of Anglo-European history.

In my last newsletter I touched on the concept of an occult summoning. Much more can be said about this, which we will hopefully explore together in the course. Today I want to explore another occult idea, that of the egregore. Egregores are collective thought-forms, vitalized by human intention, that take on a degree of autonomy — they can become beings with their own agency, their own agenda. In his book Egregores, Mark Stavish notes that the most common definition is an “autonomous psychic entity composed of and influencing the thoughts of a group of people.” He adds to this:

However, there is a second definition, an older, more significant, and perhaps frightening one. Here, an egregore is more than an “autonomous entity composed of and influencing the thoughts of a group of people”; it is also the home or conduit for a specific psychic intelligence of a nonhuman nature connecting the invisible dimensions with the material world in which we live. This, in fact, is the true source of power of the ancient cults and their religious-magical practices.”

Indo-Tibetan Buddhism uses the term tulpa, an ensouled thought-form. Alexandra David-Neel, early Twentieth Century student of Tibetan magic, called them, “magic formations generated by a powerful concentration of thought.” She also noted, “Once the tulpa is endowed with enough vitality to be capable of playing the part of a real being, it tends to free itself from its maker's control.” Neel described an experiment she made creating a tulpa of a monk, which started to develop its own ideas and inclinations. Finally, she had to dissolve it via ritual.

As an analytic idealist, I see the physical universe as a transitory projection from an instinctive, infinite consciousness that explores its creative curiosity through myriad subjective beings. What we experience as this material world is, ultimately, no different than the apparently solid constructs we encounter in dreams, which we know, upon waking, to be creations of our unconscious minds. Tibetan lamas repeatedly tell us that reality is no different from a dream or a magic spell. I don’t think we take them seriously enough!

What we encounter as the various expressions of human civilization could be described as a host of egregores: Thought-forms we temporarily vitalize. Corporations are egregores: The Nike or Apple logo are symbols that bind energy and crystallize our imaginal relationships with certain products, delivered to us via invisible supply chains. Because we are immersed in the things of this world, we don’t often step back from them to regain the sense of their strangeness and arbitrariness.

The contemporary art and literary worlds are egregores. They have their ceremonies, invocations, totems and taboos; their high priests and agreed-upon scriptures. A blue chip art gallery has the capacity to transform an object without any particular utility into something of extraordinary value, if the critics/priests make the right signs over it. The art opening, the museum retrospective, the publication, the lecture: These are ways that the consecrated value is continually substantiated.

I’m not sure that today’s financial system is much different than this. A bank, also, is a type of egregore sustained by collective human belief and trust. The egregore of our economic system is based on a set of irrational — occult — beliefs and principles such as non-reciprocity (compared to the gift economies of indigenous cultures, as defined in The Gift, an essential text from anthropologist Marcel Mauss), limitless growth, and the intrinsic value of private wealth accumulation. Perhaps we can look at today’s capitalists and “philanthro-capitalists” as “infected” by a particular egregore, which drives them ever-onward (until we hit the wall, together, soon).

As I wrote last time, I hope, in Secret Histories, to share some of my past mistakes, so other seekers can avoid similar errors. The only way I can do this is by exploring past experiences. To some, these will seem to cross the line into madness. In this regard, I intend to explore my somewhat traumatic experience with a powerful contemporary egregore: The Burning Man festival. This encounter ended with me spending a sad, solitary night in jail in Lovelock, Nevada, banished from the festival.

A group of artists and occultists, including the West Coast Cacophony Society, started Burning Man. From its origins, it can be seen as an “occult working,” a more or less deliberate summoning. The founders devised something like a new cult or postmodern religion, with particular rituals and mantras. The roots of Burning Man lead back to the ‘60s counterculture, the Leary/McKennna psychedelic lineage, Crowley’s OTO and Chaos Magic, as well as Silicon Valley’s tech idealism. Whatever was summoned forth from the event’s origin has evolved into a potent social force — but, I feel, a problematic one.

An occult force or entity hovers over Burning Man. The festival’s egregore demands acts of fealty, rituals of obedience, financial expenditure, and other kinds of worship. It is, as Stavish put it, “A specific psychic intelligence of a nonhuman nature connecting the invisible dimensions with the material world in which we live.” One finds a shared psychic field among recent participants or “Burners.” They tend to speak frequently, even ceaselessly, about their experiences, engage in various ritual acts and wear totems associated with the event. Year after year, they spend a huge amount of their free time and energy preparing for it, as if hypnotically compelled or possessed by the egregore.

Years ago, I was one of the event’s main “high priests” or scribes: I helped the Burning Man egregore reach its current level of cultural power and centrality. Enraptured by the festival, which changed my life, I wrote about it for Rolling Stone (2000), in my first book Breaking Open the Head (2002), and in ArtForum (2003). Over the years, my attitude toward Burning Man started to change. By 2006, I felt that the festival had taken a wrong turn. In 2015, I wrote an essay about my change of heart that Tikkun reprinted:

Burning Man has accomplished amazing things, opening up whole new realms of individual freedom and culture expression. At the same time the festival has become a bit of a victim of its own success. It has become a massive entertainment complex, a bit like Disney World for a contingent made up mostly of the wealthy elite. It always had this vibe, to some extent, but it seems more pronounced in recent years. It feels like there is more and more of less and less. The potential for some kind of authentic liberation or awakening seems increasingly obscure and remote. …

At Burning Man, there was always a tension between two world views, which I would characterize as libertarian hedonism and mystical anarchism. I feel, as a result of its rapid growth and, also, as the festival has become a magnet for the wealthy elite (the Silicon Valley crowd, the media moguls and their entourages, the Ibiza crowd, etc), it has tilted too far toward libertarian hedonism. Art cars have become the new yachts, representing expressions of massively inflated egos. Wealthy camps will drop hundreds of thousands on a vehicle, then parade it around, with a velvet rope vibe. Increasingly, the culture of Burning Man feels like an offshoot of the same mindless, self-interested, nihilistic worldview and neoliberal economics that are rapidly annihilating our shared life-world.

When I returned to Burning Man, I had the occult catastrophe I hope to write about next time, which culminated in my only incarceration (a fantastic teaching, in some ways). In retrospect, I felt the Burning Man egregore struck back at me for turning apostate, rejecting it, denying its faith.

Great read. I'm interested to hear your take on how the pandemic may have effected us collectively and at an individual level.

I have recently written a commentary on what it has brought about in the last few years but it was almost as though I couldn't help myself.

I'm still not sure where this compulsion is coming from as on the one hand I really want to avoid falling in to the traps of division and adding to the toxicity with my views which are unfortunately far beyond what is accepted.

But on the other I feel more people need to speak up and be brave enough to challenge the toxic status quo. And to do this in away to not fall in to a memetic tribe is pretty difficult!!

Great article! I've been fascinated by this phenomenon for some time now. Jason Reza Jorjani (a fairly controversial dude) has a really interesting take on this that you might be interested in checking out. We definitely need to be careful with our collective thought-forms in the future...