I find myself compelled to write a series of essays on Rudolf Steiner’s occult philosophy. This is the first one.

I discovered Steiner when I was undergoing an initiatory crisis induced by unprotected psychedelic use, in my early thirties. Most of my journeys were good, but a few were terrifying.

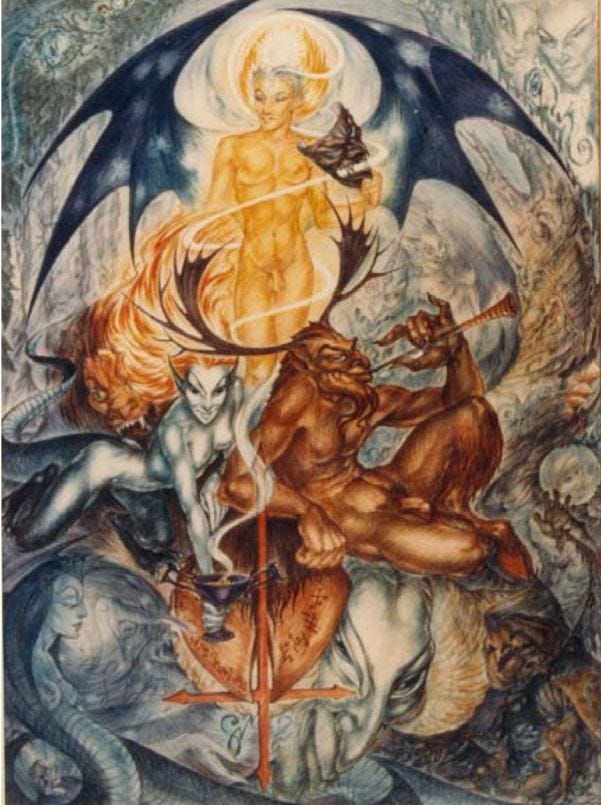

In one trip on the synthetic psychedelic DPT (I write about this episode in Breaking Open the Head and 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl), my friend and I managed to “break on through to the other side”: We seemed to find ourselves in another dimension together. This hallucinatory world was populated by vaguely velvety, taloned entities that seemed like something from Aleister Crowley’s weird imagination (with flecks of Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde). We both had the sense that these beings were arrogant, haughty, mocking us. It felt like they were having a fabulous, orgiastic party at a palatial Edwardian mansion. We had crashed uninvited, and they were annoyed.

In the weeks after this trip, I kept having visions, as well as synchronicities, paranormal and supernatural episodes. When I closed my eyes, I would see other, flickering worlds. My friend — she was, luckily, a witch — finally did an improvised exorcism with me to dispel the energy and close the gateway, which helped a bit.

This was one of a number of experiences that convinced me the occult – as described by Crowley, WB Yeats, Dion Fortune, Blavatasky, Castaneda, and so on – is not just an object of anthropological curiosity. There are occult dimensions, linked to our own. This is also why I find the current discourse on the psychedelic renaissance constrained and tame. Beyond the use of psychedelics to cure depression or boost innovation, we have bigger fish to fry!

Back then, I was looking for answers. I found Crowley’s and Castaneda’s descriptions of the occult realms to be dark, destabilizing – like taking a 4am Subway through Times Square in the mid-1970s, where nothing good could happen. I became scared that the other realms were malevolent places – the subtle realms outside of normative “Capitalist realism” were cruel, alien, inhuman. Even Gurdjieff (who still fascinates me) focused on the negative aspects. He described the Moon, for example, as a gigantic spiritual being that consumed our souls after we died. Humans seemed like helpless playthings of an occult reality beyond what we could conceive.

One night, during my crisis, I ran into Neil Martinson, an old friend. Neal had become a devoted student of Steiner’s. He lived in an Anthroposophic church in San Francisco. Over the course of several hours, he explained Steiner’s cosmology to me in a way that was deeply healing and centering. Over the next few years, I must have read twenty books by Steiner, plus tons of his lectures (which are all freely available online), along with a number of books about him. I read Steiner hypnotically, repetitively, letting his ideas and overarching thought-structure slowly seep into my Psyche.

I believe Steiner is one of the most important thinkers for us now1, even though he remains completely inaccessible to most people today. Steiner would not be surprised at this. He understood that what he called the influence of “Ahriman” – the spiritual force of rationalism and materialist technology – would penetrate deeper and deeper into the collective consciousness over the next century. The Ahrimanic influence traps people in reductive rationality, empiricism, and nihilism. Without knowing it, they lose access to what Steiner defined as our higher cognitive faculties – “intuition,” “inspiration,” and “imagination” – and lack the tools to question the prevailing ideology. Steiner’s approach to the nature of existence is so different from what we generally encounter in our postmodern techno-culture that we have to reach an entirely new perspective — a new consciousness — to access what is meaningful, profound, and transformative in his way of thought.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.