In 2016, I published How Soon Is Now, with introductions from Sting and Russell Brand (before he got all twisty and Alt Right). I’ve been reviewing this book as I prepare for Embracing Our Emergency. our upcoming seminar. I still like it but I admit I am also finding it a bit idealistic / naive. My intention was to write a manifesto for humanity — to get things moving again. I love the manifesto as a form. I am currently reading Adbusters founder Kalle Lasn’s How To Win the Planetary Endgame, as well as Andreas Malin’s How to Blow up a Pipeline: two new entries in the genre. I intend to write about them soon.

I thought I would republish a section from How Soon Is Now on revolutionary moments and movements. I hope you enjoy it — as always, I would love to hear your thoughts and ideas in the comments. One of my ideas is that we can utilize social technology to bring about a metamorphosis of human society toward truly participatory democracy, with networked local communities practicing mutual aid and breaking free of the domination/money system. Ultimately, money is just a belief system (Antonio Negri defined capital as a “social relation”). Something else — like trust or what The Venus Project calls the “resource-based economy” — could take its place. Social networks have only been around for a few decades and, even though they have been appropriated as instruments for corporate control, that doesn’t mean this is their ultimate destiny.

Revolution2.0

When the spirit of revolution arises in the people, it promises to change not only the outer world but also the inner domain of thought, dream and desire. The desire for revolution is the yearning for the decisive event that separates dream and reality – the threshold when suffering is redeemed, when freedom is gained, here and now.

The wait has been a long one. “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains,” Jean-Jacques Rousseau observed, back in the eighteenth century. “One man thinks himself the master of others, but remains more of a slave than they are.” Rousseau’s ideas ended up shaping the French Revolution.

The cry for freedom has been the persistent undertone in the music of the oppressed, those who sing for Kingdom Come, the rising of the new sun, for whom history is an unfinished melody or a call that awaits its response. The dream of revolution is a secular version of the monk’s desire for religious ecstasy, which erases the separation between subject and object, and, like fire, purifies as it scalds, transmutes as it consumes, creates as it destroys.

The Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse found civilization haunted “by guilt over a deed that has not been accomplished”, the deed of “liberation”. My psychedelic journeys made this so clear to me: We had got caught in an incessant tape loop of deferral and delay, an interminable ‘not yet’, in our agreements about reality. We betrayed the promise of past revolutions by building new prisons around ourselves – banking systems, governments, malls, corporate structures. We lost ourselves in a labyrinth constructed by the human mind.

From past revolutions, we know that “we, the people”, have the power to remake or reinvent society when it no longer serves us. This remains a strange and dangerous idea. Our civilization seeks to maintain the illusion that it is solid and permanent. Architects decorate banks and government buildings with Doric columns, imitation Roman statues and friezes that convey the sense of an ancient pedigree. All of this display is designed to fool us into obedience and complacency.

Revolution awakened the consciousness of mankind. People found, to their great surprise, that they were ‘the people’, historical actors: the subjects of history, not its passive objects.

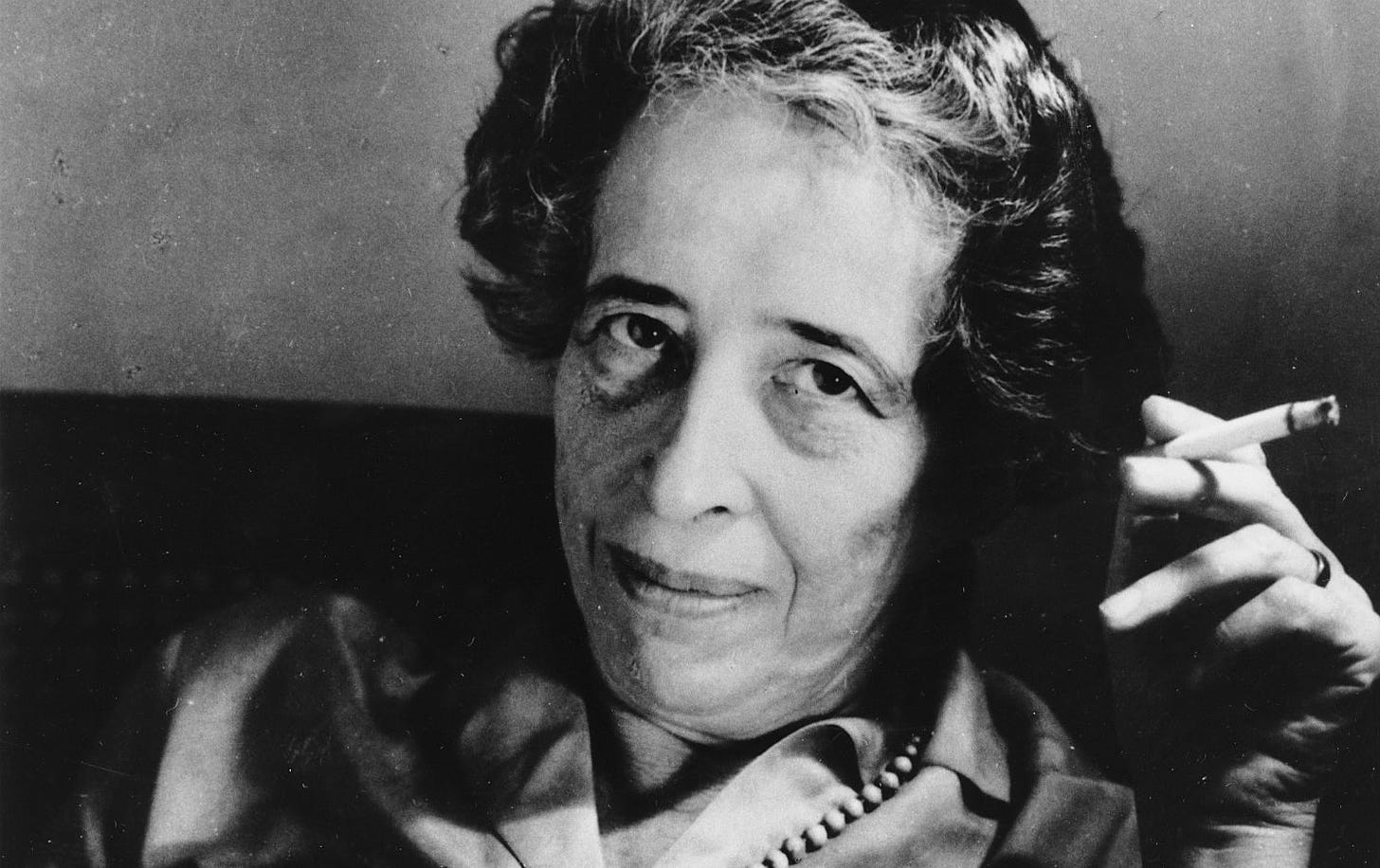

“That all authority in the last analysis rests on opinion is never more forcefully demonstrated than when, suddenly and unexpectedly, a universal refusal to obey initiates what then turns into a revolution,” wrote the political philosopher Hannah Arendt. That is the lesson of our past. We discovered it again in 1989, when the multitudes tore down the Berlin Wall, destroying at the same time an antiquated ideology.

Until the late eighteenth century, the vast majority of people believed in the Divine Right of Kings. They didn’t think of social systems as expressions of human intention, or as artifacts that could be changed or redesigned. The French and American Revolutions – deemed “the vindication of the honor of the human race” by Alexander Hamilton, or “the grandeur of man against the pettiness of the great” by Robespierre – were a shock to humanity. The people rose up to overthrow oppressive, corrupt, autocratic regimes. Through trial and error, the revolutionaries established the model of liberal democracy we know today – imperfect but a great advance over monarchy and feudalism.

Never-ending revolution remains our ideal in art, fashion and technology. Commercial society requires continuous disruption, rebellion, the shock of the new. Capitalism is brilliant at absorbing anything that might threaten it. Che Guevara becomes a face on a T-shirt. The anguish of young black men gets packaged as Gangsta Rap. Social outrage is turned into cultural product, more distractions to assimilate. The energy of dissidence and rebellion feeds the system and keeps it running.

The incessant onslaught of pop culture kitsch confuses and entrances people. We forget society is broken, that it needs to be changed, and we are the only ones who can change it. Made to believe we are powerless, we forfeit our power. It is easy to forget — until some problem leads to a crisis, and the crisis reveals a design flaw in the operating system that cannot be addressed by any reform.

Our society has revealed a number of severe design flaws that cannot be fixed within its current operating system. One is the ever-growing increase in wealth inequality. Economists like Thomas Piketty have shown that the accelerated accumulation of capital by a few is built into the system. As the middle class collapses, we are experiencing something like the return of the ancien régime, a regression to a two-tier society of serfs and overlords1.

Bill Gates and other billionaires promulgate their belief that the world is getting better for the masses via technological progress. Depending on how we look at the evidence, this belief can no longer be sustained. For instance, in the US the number of children living in poverty has increased in the last decades, to almost one-third of all children. Corporate rulers and financier plutocrats are the new aristocrats, floating above the rule of law, whether they gather in secretive meetings in Switzerland to determine the fate of the world or preen in Road Warrior-esque costumes and gobble psychedelics at Libertarian festivals.

It is true that living standards and life expectancy have gone up in some areas of the world, while poverty has increased in others. We’ve managed significant gains in some areas, but this has come at quite a cost in others. We’ve managed only a few centuries of rapid industrial progress and we’ve accomplished this feat by over-exploiting the natural world, squandering finite resources that accrued over millions of years. At the same time, the advantages of our global industrial monoculture are somewhat ambiguous, at best. The desperate poverty we continue to see around the world is a direct result of industrial civilization and corporate globalization, which has increased populations exponentially2.

The second problem, of course, is that we are careering towards ecological meltdown. These design flaws are, I believe, linked. We can’t solve one without addressing the other. I agree with the social ecologist Murray Bookchin that “The private ownership of the planet by elite strata must be brought to an end if we are to survive the afflictions it has imposed on the biotic world, particularly as a result of a society structured around limitless growth,” as he wrote in The Ecology of Freedom.

We therefore need some kind of “revolution,” but it can’t be anything like the revolutions we have seen in the past. We need one, to quote Tamera founder and philosopher Dieter Duhm again, “whose victory will create no losers because it will achieve a state that benefits all”. We must also make it a peaceful revolution – a gentle superseding of the current political-economic system, not an explosive insurrection against it. While difficult to envision, we need a gentle revolution that is, at the same time, evolution and, perhaps, revelation (if this paradigm shift includes a transition from reductive materialism or physicalism to monistic or analytic idealism, which sees consciousness, not matter, as the ontological foundation).

The United States – guarding the global empire of disorder – has turned into a massive surveillance society, armed to the teeth, with AI-powered robots, killer drones, neutron bombs, FlexiCuffs and many forms of intimidation at its disposal. Any effort to oppose this kind of force directly can only end in failure. With hindsight, we can see that many of the protest and radical movements that fought “against” the system ended up feeding and energizing it. A different approach is called for.

What we could do, instead, is use the current infrastructure to bring about a systemic transformation, much as the imaginal cells reprogram the cells that make up the body of the dying caterpillar3. Despite its military might and seeming solidity, the empire is fragile. Our global economy is floating on air, as central banks create money out of nothing and debt skyrockets faster than gross domestic product, which reveals we cannot perpetually maintain a growth-based system on a planet with finite — increasingly scarce — resources.

The Promise of Politics

What lessons should we take from the revolutions of the past? According to Arendt, human beings have an innate political ability which modern society – empire – actively suppresses. Arendt was one of the most celebrated political philosophers of the twentieth century. Born as a Jew in Germany, she studied with the philosopher Martin Heidegger, who was also her lover. A brilliant phenomenologist, Heidegger became a Nazi Party member. In 1941, Arendt immigrated to the United States, narrowly escaping the Holocaust. As a thinker, she was extremely subtle, astonishingly wise.

Arendt published her first major work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, in the early 1950s. She outraged left-wing critics by equating Stalinism and Nazism, seeing them as equally destructive expressions of modern society. She coined the phrase ‘the banality of evil’ while reporting on the trial of Adolf Eichmann for the New Yorker. In her work, Arendt sought to rehabilitate the idea of political action as something that gives dignity and value to human life – action that is necessary, if we wish to have an ethical society.

Arendt changed my understanding of politics. She noted that the word ‘politics’ derives from the word ‘polis’, the city-state in Ancient Greece. In a polis free citizens gathered to deliberate, debate and make decisions together. Arendt believes that democracy – human freedom – needs a public place where it can be practised, as Occupy Wall Street demonstrated in 2011, with the General Assembly in Zuccotti Park.

“Without a politically guaranteed public realm, freedom lacks the worldly space to make its appearance,” Arendt wrote:

To be sure it may still dwell in men’s hearts as desire or will or hope or yearning; but the human heart, as we all know, is a very dark place, and whatever goes on in its obscurity can hardly be called a demonstrable fact. Freedom as a demonstrable fact and politics coincide and are related to each other like two sides of the same matter.

By seeming to separate freedom from politics, modern society plays a trick on us. As long as we think of freedom as a purely private and personal concern, we remain unfree.

Arendt realized that Western philosophy denigrated and rejected political thought and action. Over 2,000 years ago, Western thinking turned away from politics – from action in the world – when Socrates was accused of ‘corrupting’ the youth of Athens and executed because of his constant inquiry. The impact of this was profound for Western civilization. It was like an original trauma, causing the split between thought and action that continues. Today, we still conceive of personal liberty as freedom from politics, rather than freedom to participate as authentic political beings.

Jonathan Schell wrote on Arendt:

Among the difficult things she came to understand was that the great thinkers to whom she turned time and again for inspiration, from Plato and Aristotle to Nietzsche and Heidegger, had never seen that the promise of human freedom, whether proffered sincerely or hypocritically as the end of politics, is realized by plural human beings when and only when they act politically.

Philosophy became its own specialized realm, while politics became the path for those seeking power in the world.

What Arendt called “the promise of politics” begins when we understand that our power as political beings is a living force, rooted in our solidarity with one another. Electoral politics tends to be a sad spectacle of compromise and capitulation. But that is not the real essence of politics. It is a corrupt aberration.

We are inherently political beings. Freedom is something we create, in collaboration and communion with each other.

When she studied the history of revolutions across the modern world, Arendt discovered, over and over again, “the amazing formation of a new power structure which owed its existence to nothing but the organizational impulse of the people themselves”.

Once centralized authority disintegrates, the people establish assemblies, neighborhood councils, cooperatives and working groups. They take over factories and schools and run them themselves, without bosses. They practice the direct, consensus-based decision-making found in many indigenous cultures.

The disintegration of state power inspires the immediate creation of local democracies. Arendt called them “spontaneous organs of the people, not only outside of all revolutionary parties but entirely unexpected by them and their leaders”. Decisions are made by public referendums, arrived at through consensus. The people suddenly demonstrate “an enormous appetite for debate, for instruction, for mutual enlightenment and exchange of opinion”.

Revolution is not the cause of social and political disintegration, Arendt noted, but a consequence of it.

This was true in the socialist and communist revolutions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and even in the neoliberal ‘counter-revolutions’ of the 1990s, which helped Putin gain ascendency in Russia. In On Revolution, she wrote, “The outbreak of most revolutions has surprised the revolutionist groups and parties no less than all others, and there exists hardly a revolution whose outbreak could be blamed upon their activities.”

The revolutionaries would be hanging out in the demimonde, skulking in the cafes of Zurich or Paris, writing their manifestos and screeds. Suddenly, social breakdown would start in their home country. They would return – Lenin was actually transported on a private train through Europe, to help accelerate Russia’s collapse – to foment, infiltrate and take over. The professional revolutionaries’ great advantage, Arendt noted, was not their intellectual theories or organizational talents, but “the simple fact that their names are the only ones which are publicly known”.

Arendt believed that the professional revolutionaries, full of ideological zeal, often destroyed the rapid evolution of participatory democracy that had started, as if it were a natural phenomenon, as soon as government was gone. Given power, the revolutionaries immediately established new forms of authoritarian rule or dictatorship, following abstract principles from Marx, Rousseau or Mao. When they gained control, they crushed the new assemblies established by the people. They identified these democratic organs quickly as the greatest threat to their control. When “the people in the sections were made only to listen to party speeches and to obey”, Arendt wrote, “they simply ceased to show up”.

Historians before Arendt “failed to understand to what an extent the council systems confronted them with a new public space for freedom which was constituted and organized during the course of the revolution itself”. This pattern has recurred, again and again, in modern and postmodern times. In France, a citizen’s government formed during the Paris Commune of 1871. In Russia, local councils emerged across the country during the early days of the revolution in 1917. For Arendt, councils and workers’ assemblies were the embryonic forms of an entirely new system of government based on continuous, passionate participation that could have made the gains of revolution permanent.

When the Argentinian currency collapsed in 2001, the people gathered in schools and factories to organize their neighborhoods. Workers took over the factories and continued production, forming cooperatives without overseers. Roughly a third of the Argentinian populace participated in General Assemblies, organizing locally to maintain systems for healthcare and food distribution.

Most recently, in Iceland, after the financial crisis of 2008, the people rejected the draconian dictates of the International Monetary Fund, choosing instead to evict the bankers responsible for the country’s financial crisis. Using the Internet to hold a public referendum, they wrote a new, open-source constitution, declaring their country a haven for free information.

Crisis Is Opportunity

It is possible that the next revolution will never come. Although we are in a massive, out-of-control civilization barreling towards ecological breakdown, the current system is also intricately interdependent and hyper-defended. While the underlying mechanism of the global financial system is broken, while shadowy webs of conspiracy and corruption extend everywhere, while billionaire financiers toast their own cleverness as millions lose their homes, while the planet’s eco-systems buckle and collapse, it may be the case that our global oligarchy will manage to hold it all together for a while yet – like Major Kong in Doctor Strangelove, with a final ‘Yee haw!’, riding the bomb all the way down.

On the other hand, some series of unforeseeable events may create the opening for a sudden substantive change.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Liminal News With Daniel Pinchbeck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.