Why can't we deal with global warming?

The problem is wicked, and the problem is us

Without sugarcoating the matter, I wanted to share some ongoing reflections on the ecological emergency and the future of humanity, which are — I’m sure we can agree — deeply entwined.

The latest IPCC report only reaffirms everything we already knew: We are hurting toward a cataclysm that could bring about civilizational collapse and even our extinction within a short timeframe. Nobody can predict exactly what will happen or when. That has always been part of the problem. Collapse, even extinction, could occur within this century. It could happen much sooner, in a matter of decades. An unhappy yet frighteningly real possibility is that it is already too late to change course.

It is hard to say how widely shared this understanding is. Most younger people know their future is in jeopardy, even if they haven’t studied the matter in depth. Among the young, many now take anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications regularly in order to numb themselves and avoid feeling their grief and pain. Some people still maintain that technology — our postmodern God — will evolve quickly to address the situation. But barring a miracle, our technology has no way of responding to the magnitude of the destructive forces we have unleashed.

We see rapid changes to the Earth happening all around us. These include mega-droughts, forest fires, collapse of insect populations, mass extinctions, the bleaching of the coral reefs. All of the negative consequences of human-induced climate change (CO2 pollution) intensify with astonishing speed. Because the fossil fuel companies have spent hundreds of millions of dollars over decades to spread disinformation and influence the mainstream media, a sizable subset of people remain clueless, confused about what is taking place.

Societies are built on shared narratives and mythologies. Our civilization was built on the myth of progress. Capitalism and technology were supposed to drive humanity toward a new, utopian condition. Everything was going to keep getting better forever — until we merge with our machines, attaining the technological Singularity, a silicon-based Rapture.

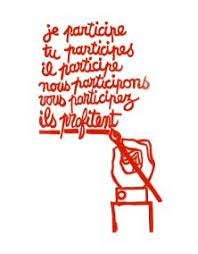

“The system” has tricked people in intricate, cunning ways. To take one example, after the mass carnage of World War Two, the ruling elites of industrial society could have chosen to apply technology rationally, with the goal of creating long-term security while reducing everyone’s working hours. Instead, the masses were forced to work harder (even as women joined the workforce) while many got sucked into an inescapable debt spiral.

In the 1950s, the Frankfort School philosophers who fled Nazi Germany analyzed post-industrial society’s “irrational rationality,” its mechanisms of re-inscribing dominance and control. These have only become more invisible and efficient since that time. The promise made by the ruling elites to the masses was that progress would eventually benefit everyone. It would lead, eventually, to a materialist utopia of creature comforts and seductive distractions. They fulfilled this promise temporarily -- for the middle classes at least — but at a great cost that is now becoming apparent.

Our system obscured the devastating impact of industrial and technological development on the Earth’s natural systems. For a while, the planetary ecosystems remained robust enough to handle our ongoing assault. Now they are starting to buckle under it.

Nobody with a successful position in the establishment dares to state what should be blatantly obvious to everyone by now: Capitalism is the problem.

Capitalism, in its current form, can never address the ecological catastrophe unleashed by Capitalism.

Capitalism is based on debt, structural instability, and cutthroat competition. Its dynamism requires incessant growth, expansion, and new markets to exploit. It is the opposite of a steady-state system.

Quite simply: “Green Capitalism,” “Regenerative capitalism,” or any fraudulent benchmarks of “corporate sustainability” all have zero chance of addressing the underlying problems propelling us rapidly toward annihilation. Why is this the case? Because the stock market, as it is currently designed, only recognizes one kind of value: Financial profit. Publicly traded companies have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize shareholder value. According to this prime directive, they must incessantly increase revenue and market share, regardless of “externalities.”

We can think of corporations as artificial life forms that humans built to compete in a game that we also invented called the stock market. Corporations, obeying this game-logic, are forced to do many terrible things. They must evade or undermine environmental restrictions, exploit resources, try to gain monopoly control, ignore the harm they may cause to local communities and cultures, and so on. The competitive pressure faced by corporations leads them to choose, as directors, sociopathic character types who feel no guilt about unleashing this type of damage.

One of the most honest books on the ecological emergency is Roy Scranton’s Learning to Die in the Anthropocene. A former soldier in the Iraq War, Scranton argues it is already too late to save our current civilization from collapse. He hopes some portion of humanity can survive the coming catastrophes by returning to humble, humanist values. Considering the reasons why the requisite scale of collective action is impossible, Scranton writes:

There’s no “reset” button for civilization, and no viable plan for transforming global infrastructure, agriculture, and energy networks in the next ten to twenty years. And while smart, dedicated, and thoughtful people fumble with political machinery that doesn’t work, such as carbon-pricing markets, protests, and the United Nations, all of us in the Global North go about our business, driving, flying, leaving lights on, running heaters and air conditioners, eating meat, charging our devices, living unsustainable lives predicated on easy consumption. …

The problem with our response to climate change isn’t a problem with passing the right laws or finding the right price for carbon or changing people’s minds or raising awareness. Everybody already knows. The problem is that the problem is too big. The problem is that different people want different things. The problem is that nobody has real answers. The problem is that the problem is us.

A while back, I realized that we have to accept “the problem is us” — all of us in the First World, myself included. Over the years, I have traveled around the world to conferences and summits where entrepreneurs, directors of nonprofits, engineers, trust-fund millionaires and the like come together to discuss sustainability, environmental issues, social inequality, racial injustice and so on. I enjoy these events, but I no longer hold any illusion that they are likely to be harbingers of meaningful change.

The reality is that all of the attendees create large ecological footprints. Taking one jet flight across the US or across the Atlantic emits several tons of CO2 — more than a subsistence farmer from a poor country in the developing world will use in a lifetime. I also don’t really believe in the delusional calculus of “carbon offsets,” as it takes a few hours to travel across continents or oceans but years to grow enough plant matter to restore that amount of CO2.

I have visited a few cultures that truly live sustainably, or at least they did so until recently. Indigenous people from the Kogi and Aruak in the mountains of Colombia or the Secoya in the Ecuadorean Amazon lived, traditionally, in a way that most likely restores carbon to the Earth rather than releasing it. They required no industrial goods or imports, no cell phones or laptops formed from plastics and “conflict minerals.” They made their own clothes and implements from natural materials sourced within walking distance of their homes. They didn't ride on planes or cars — or even horses for that matter. But nobody at any of the conferences I have attended seriously talks about a future where humanity would go back to living in that way, or anywhere near it.

Nobody has any intention of abandoning “progress” and all of its shiny accoutrements. Everyone but the most extreme, dyed-in-the-wool ecological activist is addicted to their smart phones, even if they are using it to organize protests against the ongoing extraction of fossil fuels.

So what can we do? I gave ten years of thought to this question and produced a book as my response: How Soon Is Now.

I ended up convinced that, if we want to survive beyond this threshold, we must quickly build and launch a new economic operating system for human society. This means redesigning the instruments we use to measure and exchange value. This also requires, in parallel, a change in our underlying myths and stories, which we project across the world through our media. I know this seems such a huge task that it is almost impossible to imagine. But sometimes seemingly impossible things can and do happen.

Collectively, as a species, humanity acts like a reckless adolescent in rebellion against the greater community of life. We have reached a point where we must accept the limits imposed by maturity or fail spectacularly. Capitalism forces constant growth and instability. But infinite growth on a finite planet, with finite resources, is impossible. Capitalism is also a system that excessively rewards individual success within the system at the expense of the collective. This is also, I believe, unsustainable.

To have a chance of survival, we need to radically reduce the amount of CO2 we release — far beyond the cuts mandated by the Paris Accords, which have also been ignored. This can only happen through a collective initiative and an acceptance of shared sacrifice that would transform all of our lives. For at least a few decades, there would be very little traveling and “digital nomad”-ing. People would have to accept severe limits on personal consumption and commit to building ecological communities — local utopias — in that one place where they happen to live. We would have to reorient our entire concept of work around the environmental emergency. Any large-scale activity that is not ecologically regenerative — or at least protective / conservative — must be stopped for the time being.

Paid subscribers allow me to continue my writing and research. They get discounts on seminars and other products. Soon, I am going to start weekly live calls, free for subscribers only.

Among the positive aspects of the Covid-19 pandemic is a new awareness of shared community responsibility. Climate change and species extinction threaten humanity’s immediate future far more than the Coronavirus. Perhaps this new sensibility could be the starting point for an emergent collective initiative to face the ecological crisis.

In future editions of this newsletter, I will explore more specifically how I envision bringing about this systemic change in the time we have available for it. If you want to understand my ideas on the subject, you can also read How Soon Is Now, or listen to it as an Audiobook.

Traveling has always been a part of the human experience and evolutionary growth. When we travel we spread ideas, diversify the microbiome, and expand our understanding of what it is to be human. We need to develop ecologically harmonious modes of moving around instead of eliminating travel altogether. Otherwise, your perspective is insightful and on point. Thank you.

Much gratitude for your vision and insight on global warming, capitalism, and the future of corporations. We are working on narratives for these old paradigms to flow into emerging ones.